Doom’s face

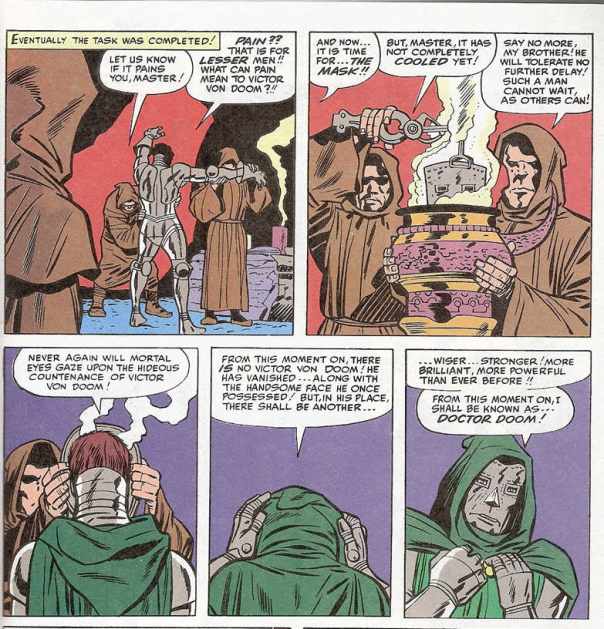

In the unbelievably awesome Fantastic Four Annual #2, when Victor von Doom puts on his mask for the first time, a minion protests, “But master, it has not completely cooled yet!” and in the from-behind panel when he’s putting it on, vapor rises from the contact point to remind us of how hot it was.

Apparently Kirby first voiced the concept that Doom’s face had only been scarred a tiny bit some time in the 1970s. Here’s a sketch he did, which has prompted astonishing loads of fanwank ever since it went on-line, about what Kirby thought was really under the mask, or what was really under the mask, and whether Stan thought something else was under the mask … To deal with the most trivial thing first, neither ever stated or implied anything about what is really there under the mask. Not even on-panel – the image leading this post is obviously a joke, which seems to be lost on fandom assembled, confirmed yet again as a humorless entity. I need to kick fandom assembled in its pimpled ass pretty hard to embed this next point: that “really under the mask” isn’t important. No, the sketch doesn’t show us what Kirby thought was under the mask. Nothing was “really” under the mask, there is no fucking mask, and no, I’m not being symbolic or PoMo – I’m talking about real live stuff. Doctor Doom’s face, under the mask, is whatever the writer and artist are doing with it, if anything, in whatever you happen to be reading. Nor does it obviate, cancel, retcon, or otherwise change what some previous writer and artist were doing. Consistency is or isn’t maintained, is or isn’t important, and is or isn’t a good thing – spin those dials per the moment.

Apparently Kirby first voiced the concept that Doom’s face had only been scarred a tiny bit some time in the 1970s. Here’s a sketch he did, which has prompted astonishing loads of fanwank ever since it went on-line, about what Kirby thought was really under the mask, or what was really under the mask, and whether Stan thought something else was under the mask … To deal with the most trivial thing first, neither ever stated or implied anything about what is really there under the mask. Not even on-panel – the image leading this post is obviously a joke, which seems to be lost on fandom assembled, confirmed yet again as a humorless entity. I need to kick fandom assembled in its pimpled ass pretty hard to embed this next point: that “really under the mask” isn’t important. No, the sketch doesn’t show us what Kirby thought was under the mask. Nothing was “really” under the mask, there is no fucking mask, and no, I’m not being symbolic or PoMo – I’m talking about real live stuff. Doctor Doom’s face, under the mask, is whatever the writer and artist are doing with it, if anything, in whatever you happen to be reading. Nor does it obviate, cancel, retcon, or otherwise change what some previous writer and artist were doing. Consistency is or isn’t maintained, is or isn’t important, and is or isn’t a good thing – spin those dials per the moment.

“OMG it’s hideous” is what most comics ran with, the most straightforward reading of the origin story. Thomas’ story in Marvel Super Heroes! #20 did it – Doom peers at his naked face in the mirror, wondering if his lost love could stand to see it, and smashes the glass, with the strong implication of disfigurement. Thor 182 shows us a bit drawn by John Buscema, which I include because no one can do the Kubert-Kubrick under-brow glare like Big John …

Which brings us to the Byrne-ian sequence of FF #278-279: Doom gains a real but not literally horrifying scar from the accident, flips out about it because he’s obviously bent about his own “perfect” self-image, then inflicts extreme disfigurement upon himself with the hot mask. Long ago, a comics pro told me it was Marv Wolfman’s idea originally, but I haven’t run into any confirmation about that and probably, either they were wrong or I am mis-remembering. I encountered the sequence when reading John Byrne’s long run on the series in one long white heat, in the pile lent to me by a friend in the summer of 1985, soon after these issues were published.

Byrne scripted and redrew the 1964 origin story using a great deal of the original composition and consistently with his general work on the book, which had developed his own homage to Kirby’s techniques.

Byrne had also put some effort in the preceding issues, and whenever he drew Doom in close-up, to show the scarring on his eyelids, for which Kirby’s renditions had not been resolved enough to establish one way or the other. I’m not sure if any other artist had done that beforehand; many have run with it since.

Was Byrne’s story consistent with Stan and Jack’s? Yes. Was it consistent with the Thomas story and the Thor story and probably dozens of minor prior references to the hideousness of Doom’s face? Yes. Was it partly (not fully) consistent with the Kirby comment and sketch? Yes. Now for the hard one: does Byrne reconcile inconsistent visions of what was “really” under the mask, creating a “really really” we can finally, relievedly, hold close to our hearts? No, it does not.

Am I anti-Byrne? Am I saying he’s wrong. No. As it happens, I thought at the time, and still think, this is a brilliant piece of writing and – as pure catnip, nothing more – a great way to utilize and honor what was previously written. For my Doom in my little fan-head, it’s the way I like it. But I’m not going to tell you that it’s what’s really there, even if by “really” we’re talking about authors’ intentions. I can’t even fathom having that conversation with you about anything in this body of multi-authored, multi-generational fiction.

I say again, the ideas that fed into Byrne’s version were not created from a canon, so all talk of the canonical “really under the mask” is completely off my mind-scape. This isn’t about the ‘Verse. I don’t care what Doom’s face “is” or whether it “was,” or if this-or-that version is “true,” or whether it was “intended” and by whom. And neither did any of the people I’ve been talking about.

In fact, it’s time to say it proud: the very concept of official canon is broken.

Just because Byrne’s depiction is consistent with the prior published material establishes nothing. A later depiction might ignore Byrne’s, or it might clumsily revise the history further by saying it was all a dream. Or we might find some depiction in Marvel Premiere or any other damn forgotten alley of Marvel comics stories prior to Byrne’s, with which his depiction is inconsistent.

Historically, there came a change at Marvel, the fervent assertion that there is a “really,” among the writers and artists, to which their work is held consistent. This assertion entered the Marvel editorial offices in the very late 1970s, in the person of Mark Gruenwald and reinforced by Jim Shooter, and became textual in 1981, with the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, and the key phrase, “the Marvel Universe.” I stress: this was an invented concoction of that very moment and in no way represented a prior standing, in-practice set of concepts.

That’s what I’m harping on: that before 1981, the pre-Universe Marvel creative culture, “shared setting” if you like although I think even that phrasing is too strong, was unregulated and unofficial. Whether Lee, Thomas, Gerber, Englehart, McGregor, or Starlin: it was nothing more nor less than a writer troubling to read earlier comics and deciding, without mandate, to use or extend what he saw there. Sometimes they did and sometimes they didn’t. Crucially, they ignored “established” stuff that didn’t interest them. Sometimes they organized it across very few titles by author agreement rather than editorial mandate, and sometimes they didn’t, and those “grand storylines” were very short – maybe eight issues! Sometimes it led to superior stories and sometimes it didn’t. It fostered an opportunistic, non-mandated, unplanned matching, which sometimes developed and assembled further and further power in the existing imagery and storylines. Certain fixed titles displayed a strong linear creative drive, but I’ll write about that later – it’s not relevant here because I’m talking now about crossing titles and authors.

Byrne’s especially strong assemblage in this case is unusual in coming as late as 1985, and it’s probably the very last great one, lifting from material before the 1981 transition from the pre-Universe, expressed after it. Consider the transition:

- Before: in which the various titles’ content affected one another or didn’t, were abandoned or utilized later, were consistent or inconsistent, based on whims – more often than previously seen in superhero comics, and no question, often used to superior effect, but that’s all.

- After: an explicit ‘Verse with its designated canon-codifier, official statements, and pre-publication continuity-checking.

I think that Byrne was able to get away with it as late as the mid-80s because he held more independent power over content than any other creator at Marvel at the time, especially in The Fantastic Four – which at the time was a beta level book, having been displaced by the X-titles. Such freewheeling content-creation and past-comics usage could get out of hand and swiftly did – I’d put Byrne’s work on this as his best moment with it, followed in not too many years by his worst, several in fact. But at this point in the history, it hit the sweet spot of raw creative engines firing hard, working from the uncertainty, the 60s-70s mutability of the material even as it’s created – the precise opposite of canon.

I suggest that this was the last moment, as well. The Marvel Universe ‘Verse eventually made it impossible for that sweet spot ever to happen in Marvel Comics again.

Pissed off? Good. Follow that ‘Verse tag.

Next: BONUS POST, April 7: Buddha on the road, Steve! Get’im!

Posted on April 5, 2015, in Storytalk, The great ultravillains and tagged 'Verse, canon, disfigurement, Doctor Doom, fanwank, Jack Kirby, Jim Shooter, John Buscema, John Byrne, Kubert-Kubrick under-brow glare, Mark Gruenwald, The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Bookmark the permalink. 9 Comments.

Hi Ron!

Honestly, I never liked that Byrne sequence. The “it was a minor scar” bit was an interesting bit of “what if” in fandom-talk (and I am 100% sure I read about it years before that Byrne story), but as a concept, it reduce Doom to a stupid fool. There was always this depiction of his ego and pride as enormous, things that could push him to act in rash way and take unnecessary risks, but the fact that they don’t overcome his intelligence is one of the things that make him menacing and larger-thab-life. If his pride is enough to reduce his intelligence to that of a moronic spoiled child (destroying his face instead of simply using his science to improve plastic surgery), then we have another Graviton, not Doctor Doom.

About the way “continuity” worked before and after 1981, something that it’s missing from the discussion is (still) the very peculiar way comics were published in the USA.

In Italy, it was ALWAYS a continuity. The “errors” were routinely talked about by fans. Why? Because of back issues availability.

When I had the money to get all the marvel comics that I had missed in the middle 70s, I could buy every single marvel comic published in the previous decade in Italy for a few cents each. They were still available from the publisher, new, for cover price, so the “street price” for used copies was less than half of that. And I could go in any of the three “used books” shop in my little town that carried comics to get the lower price.

Marvel authors could get away with a lot of “selective continuity” simply because (1) the readers changed every 3-4 years (or at least, this was the idea the writers had) and most of the new readers had no way to find the back issues to read the old stories.

If you look at French comics, the 1960s adventures of “Blueberry” for example, the continuity is very strict. And when there is a ret-con (as in some old Tin Tin books), the old book is rewritten or redrawn or both, so that the new readers see only the new version.

Italy has a (somewhat) famous case of selective continuity: Tex Willer lived the Civil War two times. Once in stories from the early 1950s, with him already over 30 years old, married and with a grown-up child, and then, in the 1970s, the same writer published stories with his “civil war memories” showing him around 20 years old and no family ties. There were more that 20 years between the two stories. The readers noticed anyway and complained to the publisher. And this was a decade before Shooter brought these changes at Marvel..

What I am trying to say its that, regarding continuity, Shooter simply simply brought Marvel to the normal standards of comics publishing in the world, and was forced probably to do so by the increasing availability of reprints (first in reprint series and then in TPBs) and comics shops where to find back issues. Readers now NOTICED. And complained.

What happened before was simply the effect of the total chaos of pre-Shooter Marvel, and the fact that marvel comics had really no permanent “memory” of anything, apart in few comics collectors that at the time were a negligible part of the readership (while in the ’80s they would become probably the whole readership)

That said, there is a very interesting phenomenon that is peculiar to the USA comic book world, and you cited it: the handbooks, the who’s who, all the compiled information that was sold to comic book fans in the USA… probably it was a byproduct of the mass of contradictory stories previously published, but it’s rather unique (at least at the time) and shows that fixation about the Marvel Comics being a “real” universe that you talked about. It’s not american-only anymore (I have seen too many young Italian fans that these days share that vision), but at the time it was. One of the first effects (or causes) of the manufactured “nerd culture” that was forming there (and later, spread far)

But if you think that these handbook were restricting what the later stories could say… if you have them, or if you can read them in some way, check the “wolverine” entry in the very first marvel handbook. I read it a lot of time ago so maybe I am misremembering some detail, but the gist of that description is totally contradicted by later stories (to the point that even the powers description was not followed). No “marvel handbook” entry ever stopped Marvel by publishing a story if they thought that it would make money!

“Continuity” in Marvel comics today is a mess even worse than in the 70s, and all what’s used for is as a “gold mine” for justifying abysmal 200-issues long cross-overs that “will change everything in the Marvel Universe” (again)

P.S.: for some example of very recent changes much more “violent” than the Byrne depiction of Doom’s face, lately Thor learned that he has a older sister (Neil Gaiman’s Angela, retconned as asgardian and daughter of Odin). You could argue that maybe Byrne was the last one to be able to made that kind of changes without checking it with a lot of editors, but I woulkd not be sure even about that. These changes never stopped happening, thought.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great comment. You’re supporting my point which is being made over many posts, even if it might not seem like it at this early stage. For the record, I do not claim the post-1981 continuity is either consistent or good. I also claim that changes made in its context are not like previous changes.

You may be missing a key phase in your analysis,which I hope to bring into the light with each ‘Verse post. Or it’s possible you haven’t spoken about it yet and I’ll enjoy your illumination as I hope you’ll like mine.

LikeLike

I personally love continuity wherever I can find it, but I totally get what you’re saying about that not being a concern for most artists and writers until it started becoming quasi-enforced. In modern times, in the cinematic stuff particularly, it can be a roadblock- No, we can’t just make a new movie with Batman or Spidey in it, we have to Establish Canon first! Ugh. No! No more origin stories, dammit! Just tell me a cool story with a recognizable version of the character in it!

That said, the concept of a MCU with a coherent, consistent continuity makes me vibrate in my seat like a kid hopped up on cadbury egg cereal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You and me both, man. I understand that attraction in my bones. I’m beginning finally to understand, though, that consistency, constraint, and some other things may be better handled as a wave-front, with a certain rueful understanding that they are tools, not ideals. And that turning continuity into a pre-ordained hard constraint is – as Moreno rightly points out – not even happening anyway. I think trying to make it happen, is like opening a door and going through, only to find that you’re on the other side of a door (the same one), which you can open and go through again … I guess …

LikeLiked by 1 person

I primarily read, and have always preferred, creator-owned books for that reason. Fred Perry’s Gold Digger, for example, has 20+ years of unbroken continuity (although he’s done some tidying up here and there). Mark Oakley’s Thieves & Kings. Robert Kirkman’s Invincible, still going strong with a huge pile of corpses and nary a retcon in sight (the Mauler Twins’ return in a spinoff book doesn’t count as it was out of Kirkman’s control). BPRD, as far as I know, has an unspoiled continuity. Colleen Doran’s A Distant Soil, likewise. Dan Brereton’s Nocturnals. Bryan Talbot’s Luther Arkwright books (which you’d love, btw, right up your alley I think). I could go on, but I’ve probably already gone too far. I mean, I love me some Spidey, and I loved Superior Spidey even more, even thought I know a year from now he won’t count, just like Future Foundation Spidey doesn’t count, and Symbiote Spidey, well, okay, he still counts a little…

LikeLike

I think Moreno has an excellent point that this transition point is not just about who’s in the Editor-in-Chief’s office, or even who owns the company and is selling the paper. This late 70s, through late 80s period is also the point where the transition from the lion’s share of money coming from newsstand distribution to the dominance of the direct market. Follow the money. Continuity, and a focus on it, and a handbook series (which I read cover-to-cover in 1987) that makes it central sells back issues! And back issues drive sales of the current books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Space Gaming News: OSR Grappling, Doctor Xaos, AVID Assistant, and Violent Resolution | Jeffro's Space Gaming Blog

Pingback: How did I get these mutton chops? | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: It is unwise to annoy cartoonists | Doctor Xaos comics madness