Scratch Pad

Posted by Ron Edwards

Here’s a little bit of history from 2004-2007, an intensive period of my work in independent role-playing activism. My priority at the much- and variously-described website called the Forge was to promote economic independence, but with a strong push to drive game design via the fun of play rather than through habit and imitation. I strove to break down the traditional dichotomy of creator vs. fan, in favor of what Paul Czege called the Hobby of Equals, and as I described it, game design is a personality disorder within the sphere of play, and game publishing is the more severe version within the sphere of design. Imagine over a decade of hundreds of independent creators busting their asses on nothing but inspiration and excitement, knowing that their work would be scrutinized, played, and discussed ad lib, but with ultimate judgment and all executive power remaining in their hands.

Here’s a little bit of history from 2004-2007, an intensive period of my work in independent role-playing activism. My priority at the much- and variously-described website called the Forge was to promote economic independence, but with a strong push to drive game design via the fun of play rather than through habit and imitation. I strove to break down the traditional dichotomy of creator vs. fan, in favor of what Paul Czege called the Hobby of Equals, and as I described it, game design is a personality disorder within the sphere of play, and game publishing is the more severe version within the sphere of design. Imagine over a decade of hundreds of independent creators busting their asses on nothing but inspiration and excitement, knowing that their work would be scrutinized, played, and discussed ad lib, but with ultimate judgment and all executive power remaining in their hands.

Many remained unpublished or published only once, many became the launchpoints for game companies you know about, and some are international runaway successes, life-transformations for their creator-owners. In a fashion probably incomprehensible except to those who were involved, the final development or success of a given project really wasn’t its greatest virtue, but rather the breaking-open of play-experience and ideas among all of us. In that, some of the greatest things done at the Forge remain invisible except as incredible mental punches that affected many dozens of people and live on in oblique ways throughout other games.

One of them which did get developed enough or almost-enough to publish but also displays that influential impact was With Great Power … (the ellipse is part of the title), written and published in two stages by Michael S. Miller, who happens to be our very own “Stalwart” here in the blog comments every so often. Now I have to disclose that he’s reworking this game from the ground up as we speak, to the extent that it’s not a revision, but an entirely new game which happens to share the title. Therefore the rest of this post is about a “dead game,” an instant turn-off for many role-players no matter how good or interesting the game in question is – it’s a “was” to them from now on, in a display of compartmentalization I’ve never understood. I’ll be writing about it anyway, so There!

Briefly to describe the overwhelming historical sweep of role-playing design: the process-based, fictional causality typically follows reductive logic, in that large-scale or very significant events only occur as the accumulated effects of small-scale quantities and effects. A punch’s success is the result of all the tiny influences feeding into it from the character’s instrinsic properties and the details of the moment, and the outcome of a fight is the cumulative result of all the hit vs. missed punches. The historical stop-motion, wargame-ish quality to the action must be retroactively edited to produce a more dynamic mental experience. Therefore the most common character sheet is necessarily both atomic and complete, to generate a literal contract for what the character is or can do, at the most minimal scale possible.

Most superhero role-playing games, and most RPGs in general, offer streamlined processes but ultimately not very notable changes to these features, with a strong tendency for the unchanged procedures and habits of play becoming their own genre, a topic near and dear to the late K. C. Ryan’s heart and which I’ll develop in other posts.

Some games have offered more substantial, experiential, but still deeply embedded changes – the original Champions (editions 1-3) is a good example, as is the 6th edition, both of which were and are frequent topics here at the blog. In these, a number of rules concern not what can or can’t be done via in-fiction-physics, but what is permitted to happen and not to happen relative to certain items. These are more innovative games which solve certain difficulties arising from the most common framework, still mainly within the most-common and historically-cemented concept of what such a game is and what its instruments of play should be.

WGP‘s Scratch Pad concept instead offered a higher-order change, as a refinement of the fact that a lot of people use scratch paper to brainstorm characters anyway, prior to formalizing stuff on the official sheet. In this case, though, the idea is that the traditional character sheet holds a subset of character content which is formally put at risk, and it’s only operative for a given story-sequence and then set aside; to play the character in a new arc, you make up a wholly new one. You keep using the same Scratch Pad as you go along, and the content on it which you don’t use stays undefined in a number of ways. In the long run, the content written on it could be:

- Never even used or referred to, and thus “not real,” on the sheet only as an artifact of brainstorming

- Occasionally mentioned or depicted in play without much consequence or importance, like a lot of characters’ alleged scientific or scholarly competence

- Mentioned and described in play but inviolate (“Batman is an unutterable bad-ass at hand-to-hand combat”)

- Put onto the formal character sheet for a given story sequence, then it becomes at risk after all, which would be a really big deal if it had previously been used as the above bullet-point (like, “Bane beats up Batman and ruins his fighting ability.”)

You gotta know what you’re doing here – the Scratchpad is the real sheet in the longer arc of play. Formal sheets are temporary, used only for single story-sequences each, but they’re consequential, as what happens to them gets changed on the Scratchpad if it’s extreme enough in play. The last thing you want on one of those formal sheets is the content you can’t bear to see altered, especially in the first story. Maybe you’ll keep that content in that state forever. Maybe after a few stories you’ll loosen up and put the “sacred” stuff at risk after all.

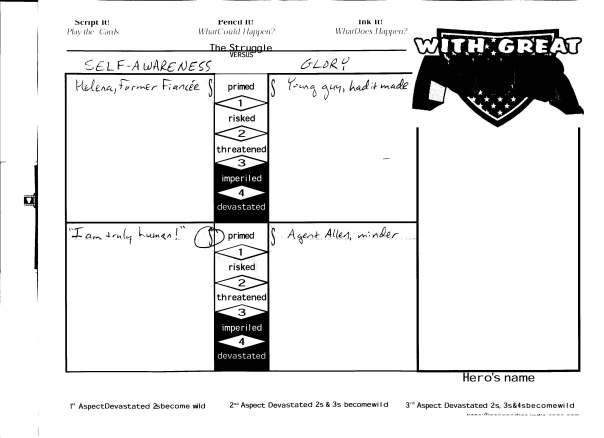

Unfortunately I don’t have the materials from my playing experiences for the game easily at hand, so I have to make some shit up. Here’s what a starting Scratch Pad might look like:

So the formal character sheet would only feature some of this, which are called Aspects and which, if they weren’t already, are organized into categories of importance to the character: Asset, Motivation, and Relationships (each has some listed subsets). For Reptron, some were categorized on the pad and some weren’t. I might start with:

- Asset (Origin): “young guy, had it made”

- Motivation (Conviction): “truly human!”

- Relationship (Romance): “former fiancee, insists she still is”

- Relationship (Partner): “overly protective minder/spook”

You also assign each Aspect to one or another side of the current designated Struggle for this story-sequence, which I’m not going to go into here – only mentioning it so you won’t wonder what that is. Like so:

By definition, putting those things onto the sheet puts them at risk for the mechanics of play called, dramatically enough, Suffering, which you can see proceeds in stages to possible Devastation. At that point, it can be captured by a villain and is subject to Transformation, and into what isn’t made up by you, but by the GM in terms of the relevant villain’s outlook or goals. You even designate one as the villain’s favored target; that’s what the circled “S” is, for Strife. Therefore this sheet is a this story this time document for what things about the character can be treated as potential crisis-points and points-of-change. Which ones and how much, well, that’s what we find out through play. You have to use all three categories for 3-6 things, but if you choose four or more you get an interesting profile – in my example, with four, it’s skewed a bit toward Relationships, and since I chose the “origin” subset for the Asset rather than a Power, you can see this will be a social-psychological crisis more than a straight-up combat victory one.

By definition, putting those things onto the sheet puts them at risk for the mechanics of play called, dramatically enough, Suffering, which you can see proceeds in stages to possible Devastation. At that point, it can be captured by a villain and is subject to Transformation, and into what isn’t made up by you, but by the GM in terms of the relevant villain’s outlook or goals. You even designate one as the villain’s favored target; that’s what the circled “S” is, for Strife. Therefore this sheet is a this story this time document for what things about the character can be treated as potential crisis-points and points-of-change. Which ones and how much, well, that’s what we find out through play. You have to use all three categories for 3-6 things, but if you choose four or more you get an interesting profile – in my example, with four, it’s skewed a bit toward Relationships, and since I chose the “origin” subset for the Asset rather than a Power, you can see this will be a social-psychological crisis more than a straight-up combat victory one.

This doesn’t mean Reptron can’t use his robot-suit reptile powers or anything else that remained on the Scratch Pad during play; far from it – in fact, those powers can now be almost godlike in the fiction, in having no chance to fail and no way to be harmed during this story-sequence. But on the other hand, they are only Color; they can’t operate mechanically all by themselves, only as incidental description or in the service or illustration of the things which are listed. If he beats the crap out of the villain at the climax of the story in a bravura display of exoskeletal cobra-tuatara-alligator abilities, it’s going to be because his reptile powers are firing in the service of one of those, say, his Relationship with Helena which is being Devastated.

Another way to look at that is, sure, Batman’s fighting skill could be unbeatable and inviolate because it remained on the Scratchpad during a given story-sequence against the Joker … but that also means it’s not what can stop the Joker or prevent the villain’s actions from doing terrible things to one or another things or people that Batman cares about, at least not all by itself. He can tear up the scenery with his bad-ass fighting, including thugs and minions, and it can serve as a visual augmenter to whatever Batman does do against the Joker, but it won’t solve the threats to his cherished things by itself.

See how subtle that is? Visually, he could beat the dogshit out of the Joker, and if that’s a subset or in-the-moment expression of whatever is on the sheet, then it “counts.” But while it remains on the Scratch Pad, that ability in isolation doesn’t have any effectiveness at that level.

OK, back to Reptron. The processes of play may alter the listed content of the formal sheet, so after an initial story it might look like this.

Most of these will “revert” at the end of the story-sequence, even if they were Devastated, but some might be captured by the villain and Transformed, for good or ill. Those will change the Scratch Pad. Here’s a conceivable successor version of the Scratch Pad after a couple of stories or as we say now for some reason, arcs. Here you can see that former fiancee Helena has become the dreaded Cobra Queen, and that the “emotion power-pack” of the exoskeleton is now the more negative Berserker quality (it must have been used and Transformed in a later story). There’s also some notation indicating that the “I am truly human” quality was threatened at some point, probably in the first story when it was on the sheet, but was ultimately recovered.

Most of these will “revert” at the end of the story-sequence, even if they were Devastated, but some might be captured by the villain and Transformed, for good or ill. Those will change the Scratch Pad. Here’s a conceivable successor version of the Scratch Pad after a couple of stories or as we say now for some reason, arcs. Here you can see that former fiancee Helena has become the dreaded Cobra Queen, and that the “emotion power-pack” of the exoskeleton is now the more negative Berserker quality (it must have been used and Transformed in a later story). There’s also some notation indicating that the “I am truly human” quality was threatened at some point, probably in the first story when it was on the sheet, but was ultimately recovered.

The hypothetical player could easily add a few more things onto the Scratch Pad along the way, which is perfectly OK. Its purpose as brainstorm device never goes away.

See too, how responsive this system is to your creative drives for a given arc. I could play a character whose general personal life and social situation, or most of it, is simply never challenged, typically making Aspects out of Powers and typically protecting the few Relationships and Identity Aspects during play. This way, the Kents’ role toward their adopted son never wavers and the fundamental relationship with Lois doesn’t change, but Superman’s powers and his backstory/origin are always being hammered and most of their details are in flux. Then one day I decide to get really personal and change it all up regarding what sort of things come under pressure, almost to reboot extremity.

What’s subject to change is always chosen by the player for each Struggle (story arc). It could be all over the place across many elements as implied by the above. Alternately, a very few things might change, meaning, there’d be a lot of change about successively-replaced stuff, but the majority of the Scratch Pad wouldn’t be touched, for an extremely focused character history through play. For example, his armor/exo-skeleton/robot body might have been made an Aspect at the start, and then undergone successive Devastations and Transformations, if that’s what the hypothetical player glommed onto and decided to keep drilling into. Or instead, one of the components of identity and self might have become the exciting and engaging nexus of conflicts for this character during the course of play, leaving the armor/powers/appearance mainly untouched.

It’s not all just the player, though, because it’s the GM who decides what feature(s) on the sheet is hammered at by the villain’s or other characters’ actions, and the mechanics of play will affect which ones get hit the hardest. Both player and GM have input into these things but no one truly controls them or their outcomes.

This final iteration of the intended design never quite came together. There were several levels at work: a dichotomy called the Struggle (which you can see on the sheet), the villains having Aspects of Suffering too, the math of Transformation, the management of several decks of playing cards through different stages of play, the late-stage addition of a villainous Plan with aspects of its own, and more. These levels weren’t always mutually supportive, and most playtesting stayed within a single Struggle and character arc, a bit obsessed with never being Devastated even though, frankly, which of your Aspects get savaged and possibly Transformed is really the whole point.

Therefore the core importance of the Scratch Pad never really got developed either in the text or in the game’s history of play, which was itself unfortunately far under-served anyway, but I think it’s the single strongest feature. It also may be the strongest practical connection I’ve seen between role-playing as a mechanics process and superhero comics as a creative medium. Variations in the usual design of “pick an origin” then “pick a few powers” and “here’s how you hit,” listed on a standard character sheet as the sum total of the character as playable device, are trivial in comparison.

A related topic for thinking about the game is the so-called sadistic choice, in which the hero is forced to save or solve one problem at the expense of acting toward another, such that the latter must be sacrificed. It’s classic zero-sum, in which the villain holds complete power over the framework of the hero’s choices. The game text refers to it as important a couple of times in principle if not by name, and the cover illustration depicts it in detail. However, in practice, such scenes are rare in superhero comics and in the few that appear, it’s a central part of being the hero to reverse the villain’s overall power, such that the hero intelligently or determinedly cheats his or her way out to solve both problems or to render the consequences of both less terrible or to force the villain to abandon the whole thing. It seems odd to me that this trope is often cited for the genre when it’s actually a pretty minor element.

For example, Gwen Stacy’s death wasn’t a sadistic choice at all, it was a straightforward murder. Get away with all your maunderings about her neck snapping when Spidey caught her; the Goblin is responsible for her death, done. Focus on my point: there was no carload of children hanging off the other side of the bridge, no “save one but not the other, boohaha.” Her neck didn’t break because Spider-Man had to do something else at the same instant.

I can see why the concept got picked up for the game: its title, the concept of the dichotomous Struggle defining each arc, and the likelihood that one or more of the chosen Aspects for play would be Devastated and possibly Transformed because others were given higher priority in the heat of the moment, all play into it together at face value. However, on closer inspection, none of these tie into the classic sadistic choice particularly; e.g., the death of Uncle Ben isn’t one either, but rather the consequence of a moment of immature selfishness.

I can see why the concept got picked up for the game: its title, the concept of the dichotomous Struggle defining each arc, and the likelihood that one or more of the chosen Aspects for play would be Devastated and possibly Transformed because others were given higher priority in the heat of the moment, all play into it together at face value. However, on closer inspection, none of these tie into the classic sadistic choice particularly; e.g., the death of Uncle Ben isn’t one either, but rather the consequence of a moment of immature selfishness.

Anyway, so there you go, two incredibly fruitful ideas, one well-conceived and almost-successful as I see it, and one misstep or semi-misstep which is nevertheless full of food for thought.

Is this iteration of With Great Power … dead? Irrelevant? Useless? Dismissed? I don’t think so. Mike has provided immeasurable service here. Let these be seeds in that part of your mind where new games grow.

Links: [With Great Power …] Brief but strong play in Sweden, “We are who we choose to be” (re: the sadistic choice)

Next: What you mean “we?”

Posted on July 9, 2015, in Heroics, Supers role-playing and tagged Gwen Stacy, Hobby of Equals, Michael S. Miller, sadistic choice, scratchpad, Suffering, With Great Power RPG. Bookmark the permalink. 15 Comments.

Excellent points, Ron! I had always hoped the Scratchpad would have bloomed into something more, but long-term play has never been my strong suit.

Embarrassing confession: I’ve never actually read the Gwen Stacy’s death issue. I knew the story from reading The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe from cover to cover when I was in seventh grade. And I could have sworn there was a bunch of innocent under threat, as well. I’ll have to see if I can find the issue of the Handbook to confirm, but that won’t happen any time soon. Back issues like that simply weren’t in my budget at the time, and the only compilations I knew about were the expensive hardcover Marvel Masterworks. Now that I have access to Marvel Digital Unlimited, I simply don’t have the time. I still need to make the sadistic choice with my reading time!

LikeLike

I bet one of our digital warriors among the usual commenters can help us out there. It’d be fascinating if the [cough! the thrice-damned abomination] I mean, Official Handbook misled you.

LikeLike

My experience w. comics is really limited. I really only got absorbed into staring at the pictures when I was quite young. I usually just borrowed the titles that friends collected and then I was following the story and not really grooving on the pictures. But I am still fascinated by supers games. I remember trying out Villains and Vigilantes and then Champions. I still haven’t had a bang on supers gaming experience. I am going give Capes another shot soon. The sessions I have played reminded me of the earliest comics experience, that panel-by-panel absorption in the images. But thanks for the reminder about WGP.

LikeLike

My recommendation is of course Doctor Xaos, for which playtesters report the “panel-by-panel absorption in the images” is tiptop.

LikeLike

The “sadistic choice” is very rarely really present in a super-hero comic (and when it is, it’s usually the sign of a very poor writer trying to add “drama” by ruining characters), but it’s very often menaced, hinted, or present in the villain’s plan anyway.

Because it’s the fodder for one of the most triumphant “hero’s victory” ever: the villain makes you choose in a sadistic choice… and you save BOTH of the important thing/persons at risk, defeating not only the villain but the world he has built for you. It’s the stuff memorable story arcs are built upon.

LikeLike

Exactly. It’s all about whether the villain controls you. Being forced into making the choice is losing that battle. I’d put it into the “can he shake off the mind control” non-question category, except that it’s so rare that I don’t think it qualifies as a genre feature.

LikeLike

This reminds me of what I always say about the Three Musketeers. They didn’t take Swordfighting Level 9000 so their story would be all about how many of Richelieu’s guards they kill. They took Swordfighting Level 9000 so their story could be about something OTHER than how many guys they kill. A phenomenon all too common to physics/combat focused games- if you want to survive long enough to do whatever you envision as cool about your character, you’d better be combat capable. In the case of the Three Musketeers, they NEVER LOSE a swordfight, but that doesn’t really matter, because, as you point out, the swordfights are all just set dressing, a chance for the heroes to show off and look awesome in between the dramatic scenes. And of course if they ever DID meet a swordsman their equal (who wasn’t one of them, of course), it’d be a hella big deal in the fiction.

So, basically, yeah. What you said.

LikeLike

This scratchpad concept, and choosing what is going to be affected by story, interests me. I’m here questing for simple story prompts for solo comics panel making . Just that sheet idea, and maybe add in ‘devastated’ as a valid modifier to the scratch sheet (it seems to make sense to me) for further story, you have a character embracing some good conflict and changing. Ideas on how this artist could pull this off don’t belong here, but here is my placeholder for saying ‘Wow!’ and potentially, if it helps make a story on my own, ‘thanks’!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Deeply appreciated!

LikeLike

Pingback: Dark Omen | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Not a dream | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: With more power … | Comics Madness

Pingback: Dynamic mechanics | Comics Madness

Pingback: A fearful symmetry is born | Comics Madness

Pingback: Oddities and experiments | Comics Madness