A dangerous vision

Posted by Ron Edwards

September is Cosmic Zap month here at Doctor Xaos Comics Madness. I’m talking now about what was going on in science fiction and fantasy at the time, which is too huge to summarize – it has to be like one of those fragmented memory/epiphany scenes in a movie, with rapid, too-short shots interspersed with someone’s face going “AAAAH!” and maybe cloth-ripping or fake-Latin chanting sound effects.

September is Cosmic Zap month here at Doctor Xaos Comics Madness. I’m talking now about what was going on in science fiction and fantasy at the time, which is too huge to summarize – it has to be like one of those fragmented memory/epiphany scenes in a movie, with rapid, too-short shots interspersed with someone’s face going “AAAAH!” and maybe cloth-ripping or fake-Latin chanting sound effects.

There isn’t really a beginning to it, and definitely no real genre boundaries in practice. Fredric Brown. Ray Bradbury. C. L. Moore. Fritz Leiber was a giant long before “the sixties” and only became more so. The crucial political/literary venue of Playboy. There’s the lesson of Vonnegut: lauded for crossing venues of promotion and review, not content. I’ll go with one shattering landmark though, from 1956: Alfred Bester, The Stars My Destination – the book to which an incredible amount of SF ever since is merely a footnote.

The sword-and-sorcery revival wasn’t only Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith, but the recognition of those who’d been battering away at it more recently, including Leiber, Leigh Brackett, Gardner F. Fox, and Jack Vance. It was contemporary with the Tolkien revival, and similarly nabbed by the counterculture and political dissent – torn from the hands of zine writers and instantly in synergy with music and comics. Also, Moorcock’s earliest and best work was earlier than one might think, back in the mid-60s. So the old and the ongoing and the new exploded into visibility all at once, pretty much simultaneously with my learning to read.

My thing is social science fiction, but not tendentious, not chin-stroking “what if,” but as visceral and as (yes) problematic as possible, ripping emotional honesty and intellectual savagery right out onto the page and saying “deal with it.” That’s why science fantasy and sword-and-sorcery go with it sword-in-scabbard. This entire complex features the entire political spectrum because it’s not neutral or “balanced,” but instead most effective and fun at its most provocative. [side point: the real category is obviously fantasy, with science trappings, politics, far-future, mythic past, and others being non-exclusive subsets, but enough of that here] It’s all dangerous, off-message, weird shit.

That southern California scene was clearly insane, full of brilliant depressed loonies, con-men or near to it, and savage ranters, all of them with one foot in The Twilight Zone / The Outer Limits both literally (professionally) and mentally. Philip K. Dick was not then a fan-fave or status-read like he would become in the 90s – I think maybe he was too raw, too spot-on, and too painful, until an audience came along that was disconnected from the politics and more interested in adaptations and cachet.

Star Trek, pre-franchise – the show itself, then fandom, then conventions, the cartoon, and the Federation Outpost

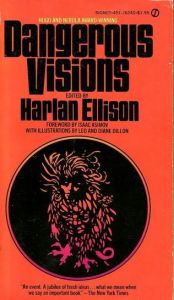

Ah, granddaddy Harlan – so much stuff to feel and say. I guess I should confess that from about age 12 to 22, I wanted to be Harlan Ellison, until I realized that he was simply a human who had perfectly understandable limitations in every way, and that I was already more like what I wanted to be than he was. Since then I’ve preferred to consider only the author at his best, the creator of the Ticktockman, Catman, Vic & Blood, and so many other incredible ideas/characters, and especially not to concern myself with the person or, for that matter, with SF fandom culture at all. I don’t think anyone’s going to have meaningful perspective on his work and influence until maybe another five or six decades from now, and at the moment, I find myself more happy contemplating him as direct and indirect mentor to generations of authors.

Ah, granddaddy Harlan – so much stuff to feel and say. I guess I should confess that from about age 12 to 22, I wanted to be Harlan Ellison, until I realized that he was simply a human who had perfectly understandable limitations in every way, and that I was already more like what I wanted to be than he was. Since then I’ve preferred to consider only the author at his best, the creator of the Ticktockman, Catman, Vic & Blood, and so many other incredible ideas/characters, and especially not to concern myself with the person or, for that matter, with SF fandom culture at all. I don’t think anyone’s going to have meaningful perspective on his work and influence until maybe another five or six decades from now, and at the moment, I find myself more happy contemplating him as direct and indirect mentor to generations of authors.

But please do consider the impact that Dangerous Visions had on a young reader, and even more so, the second collection which holds so much astonishing power I cannot even begin to talk about. Not only did dozens of new authors launch from these, but the relatively established ones who participated all went through doors of escalated ambition and technique which literally became a literary revolution. Norman Spinrad. Roger Zelazny. Gene Wolfe. Tanith Lee. Avram Davidson.

Naming these and thinking of all the others in a jumble reminds me too of tie-ins not with other SF but rather with specific branches of literature, whether pulp detective or existential lit or ancient classic theater, or especially, other current fiction which for one reason or another didn’t get genre-tagged (or smeared) as SF, like A Clockwork Orange or a fair amount of Roald Dahl. If you read this, you were also reading Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Herman Hesse, Luis Borges, John Hersey, Kobo Abe, John Gardner, Carlos Fuentes, Yukio Mishima, Edward Abbey, and Vladimir Nabokov, to say nothing of Fyodor Dostoevsky and Albert Camus.

Time to hurt you again: Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke weren’t a triumvirate of gods. They were merely the authors whose old work could be easily re-issued and whose new work could be beefed into mainstream promotion – mainly because it was politically and culturally “questioning” without being confrontational. Go ahead and point to two or three good stories from each, and I’ll nod; that doesn’t change anything. 2001: A Space Odyssey pretty much sucks. And yes, Dune too, and Herbert as a writer in general: beta at best, and usually considerably lesser. Once you read Leiber, calling these three/four the “greats of science fiction” is merely laughable.

In the U.K., they (or at least Judith Merrill) called it the New Wave, and I remain unconvinced. Editor Brian Aldiss promoted and wrote perhaps the most boring ouevre in the history of letters. Lots of that deliberately experimental stuff was posturing gibble-gabble, and arguably that’s when Moorcock stopped writing and started adding. Then again, I do like Jerry Cornelius for reasons I cannot explain well, and I also think his best book is Breakfast in the Ruins, which is as textbook avant-garde as it gets (not ordinarily a compliment from me). And of course there are these emergent gems from that scene, not to be missed.

By the early 70s, the bookstores were suddenly a big cultural and social thing, and the relevant section featured an amazing explosion of five decades of fiction all suddenly appearing at once. The publishing houses were fearless, hiring bright weird people to be the editors for anthologies and for in-house lines of paperbacks – throwing out some names at random like Bantam Spectra Editions, Byron Preiss, Damon Knight, or that anyone of my age can spot a DAW or Del Rey cover spine from 50 yards. The stores became indescribably cool: pillows, cats, candles, coffee, … and women. Lots of women, five to ten years older than me.

Kid fantasy, for which Lewis is only a start: John Christopher, Lloyd Alexander, John Bellairs, that “steel magic” book. The greatest coloring books ever, from Troubador Press:

There were tons of these, including beautiful natural history, mythology, zodiac, and more. Why every kids’ store is not loaded with them to this very day, I have no idea.

Oh! The crucial role of The Planet of the Apes, as individual politically-powerful films sprung from the awesome presence of Rod Serling, as the marketing push of 1974 (Go Ape!!), as the first major SF franchise including a brief but pretty good TV show and a shockingly edgy Saturday morning cartoon, and as a case study of all its hard-won intellectual capital going flush due to factors which still demand a thinking dissertation. One only need watch the first couple of Apes movies, without distraction and without your buddies hollering memes, then the first couple of Star Wars ones, and tell me what you see happening before your eyes.

The Apes were the standout among an incredible feast for the low-budget, edgy movie-goer, which included the full range from brilliant to wretched and often a mix of the two: Zardoz, A Boy and His Dog, Silent Running, Soylent Green, and so many more, culminating in arguably the worst ever made relative to its cultural “gonna be such an event” buildup, Logan’s Run.

Who knows what’s going through your head throughout this montage. For me, the net take is that “problematic” is a good thing, and God knows there was enough of it to work with; check out Piers Anthony’s Battle Circle some time. I’m thinking too of all those books that I can’t imagine any modern SF fan I know reading in a million years, including authors Julian Jay Savarin, John Robert Russell, Barry Malzberg, Arthur Byron Cover, Andrew J. Offut, George Alec Effinger, Kate Wilhelm, Robert Stallman … my point being that every one of them would yield a whole term’s dedicated and frightening debate in a decent college course in culture/lit/polysci, if any such could be located. Say it again: problematic is good. Only too far is far enough.

And the music just kept coming. Did I say Julian Jay Savarin?

In line with the sudden thaw in U.S.-Soviet relations, all this generally eastern-bloc SF suddenly hit the shelves, just as interesting in its painful and confused framing for U.S. audiences as in its remarkable excellence – or at least in what I read, especially Lem and the Strugatski brothers, no surprise to anyone.

And the painful attempts at big-budget cosmicity: every publisher wanted another Stranger in a Strange Land or Dune, so they tapped authors all over to deliver big fat profound novels, often well out of that author’s groove or skills. Anderson’s Avatar, Anthony’s Macroscope, tons more – you’re lucky if you get a glimmer of a good idea in the first couple chapters, just as in the more famous ones.

How can I possibly explain it? The politics of the day rocketed up and down and sideways among SALT, Watergate, Vietnam, the SLA, Weather, the Black Congressional Caucus, and revolution/counter-revolutions exploding across Latin America and Africa. You can’t go by “decade,” you can’t even go by year – each new creative product needs to be understood in its month of creation and publication. And even more so, each such product appeared in a weird and complete identification among book/music/movie/comics, with strangely, TV as probably the lesser partner in this mix. Any one of these could inspire or be the first expression of a story that showed up across all the others, whether as adaptation or rip-off or continuation.

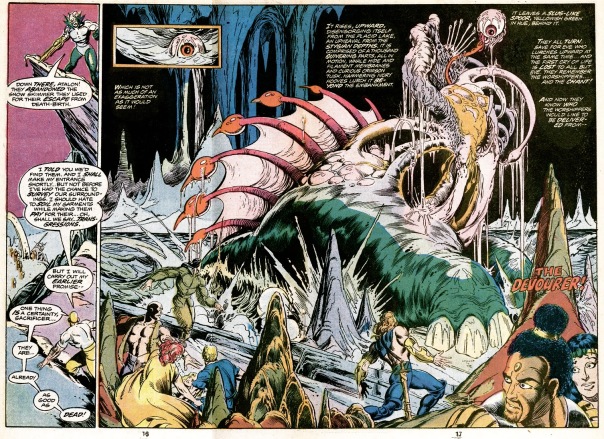

Comics – like I said, it’s a matter of instant synergy. It’s impossible to summarize the adaptations left and right (Lord of Light, More Than Human, Jerry Cornelius), and of how much, e.g., not just Conan but Howard’s poetry. I think it was the most apparent among the dystopic subset including, in rapidly descending order of quality, the black-and-white Planet of the Apes (which was terrifying), Deathlok, Killraven (which preceded Zardoz, for you fashionistas), Bloodstone, Skull the Slayer … the fall-off after about 1977 is significant … and I feel a whole post of crazy talk coming, so I’ll sign off on that for now. My point is that one didn’t read, say, Killraven in isolation as “a comic book” – the experience was all wrapped up this crazy complex of multiple media, perspectives into past work (in this case War of the Worlds), and immediate political context.

Here’s where Metal Hurlant fits in, especially with its adaptations of, among others, More Than Human. Again, it’s not merely “comics,” but comics/books/films/everything, and again, past and present works arriving in a new sea of sensation and interpretation. I still cannot understand the mid-late 80s fetish of the “new” graphic novel, not when I was reading Chaykin’s adaptation of The Stars My Destination years ahead of that.

Here’s where Metal Hurlant fits in, especially with its adaptations of, among others, More Than Human. Again, it’s not merely “comics,” but comics/books/films/everything, and again, past and present works arriving in a new sea of sensation and interpretation. I still cannot understand the mid-late 80s fetish of the “new” graphic novel, not when I was reading Chaykin’s adaptation of The Stars My Destination years ahead of that.

I just remembered too: all those repeated attempts at prose-comics hybrids in mass-market paperback format, ranging from Gil Kane’s Blackmark to Byron Preiss’ edited series Weird Heroes to the compilation of Marvel’s Star Wars – no one knew what to do with this “comics are awesome” insight and somehow discovered every format that wouldn’t work.

I hate to finish on a bummer, but by the mid-80s all of this had become a dream, absent not only from the landscape but evidently from memory. I’d put 1986 as the clincher year, featuring the original Robocop as the last truly great SF film and Aliens as the first excellent science-trappings action film. But it had been coming for a while, with the exercise in emptiness Star Trek: the Motion Picture in 1979, the occasionally charming but not very heavy-metal Heavy Metal movie in 1981, and that wretched farce The Return of the Jedi in 1983. But that’s movies; in comics … it was gone well before then. It’s one with the vans, become hip memes for glitzier films and GIFs to mine, or viewed as an incomprehensible alien past.

Links: War of the Worlds

Next: Superstar

Posted on September 10, 2015, in Politics dammit, The 70s me and tagged Dangerous Visions, Harlan Ellison, Hawkwind, Killraven, Metal Hurlant, Oodles of titles, Planet of the Apes, Rod Serling, Star Trek, Troubador Press. Bookmark the permalink. 30 Comments.

I had that Monster Gallery book! I loved that book. Have to see if I can track down a copy that’s in decent condition and not colored in. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. This nails the moment spot on. It only took me 2 years to go from Wind in the Willows to LeGuin and Dangerous Visions. And those books is were in my Middle School and High School libraries, along with issues of Analog. This was a paperback, 2nd hand, low tech stuff. When Star Wars came it was as if a tiny tip of the ice berg had made it a into the Mall movie theatre. I remember the idea that you could RPG the things you were seeing in movies suddenly becoming apparent. Shogun the TV series synced up with Bushido and the Raiders’ movies synced up with Daredevils (from FGU both). So if The writers of Runequest and Tunnels and Trolls take “the culture” and make games, I get “the culture” and have games and movies hitting at the same time (1979-1980). Pink Floyd’s “See Emily Play” and “In the court of the Crimson king” playing on the classic rock station is the soundtrack to and reflection of childhood daydreaming to adolescent cosmic trip-out fantasy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was tending to a feverish kid over a holiday weekend while finishing this post, so some names got dropped. I never intended this post to be a completist treatise anyway, but I’ll fill’em in here as they occur to me, editing as I go.

John Brunner. Philip Jose Farmer. Joanna Russ. David Gerrold. Jerry Pournelle. David Mason. Fred Saberhagen. J.G. Ballard. James Sallis. M. John Harrison. Ben Bova. Terry Carr. Thomas Disch. Greg Benford. Richard Lupoff. Alexei Panshin, Gordon R. Dickson, Gardner Dozois, Pamela Sargent, Donald Moffitt, Michael Kurland. (older) H. Rider Haggard, James Branch Cabell, Aldous Huxley. I also forgot my plan to showcase Larry Niven as the dictionary-definition rapid slide into mediocrity for the entire genre, but the bum-out I mentioned in the final paragraph set in – it was too grim actually to do.

Note – I’m not saying I like all the authors I mention, only that they were contributing significantly to the whacked landscape of available and above all unconstructed, non-bounded letters I’m talking about. Frankly, most of them in this comment and in the main post were hit-and-miss at the best of times.

LikeLike

I was about to start complaining about the sacrilegious things you wrote about the holy trilogy of sf…. and then you compared them to Leiber. Not fair, Ron, not fair. (I read in some post online that Leiber is little known these days? How that’s possible?).

This reply will jump from topic to topic trying to follow the stream of your post, there is really too much to talk in it (you drop “The stars my destination” in a phrase and you leave it at that? I want an entire post about Bester!). I recognize a lot of what you write about, bit some bits missing (no PotA cartoon here), some rather important (Dangerous Vision was not published here like a single book, I could read only bits and pieces), but yes, the general picture is one I recognize.

The english “New Wave”…. some of it made me angry, some of it I loved (Thomas M. Disch short stories haunted my imagination for years), most of it puzzled me (ehi, I was 13 at the time I read them!)

I loved problematic stories, even if at that age “problematic” cut a wide path around the political, the personal and the cultural… fra “Davy” by Pangborn right in the precise moment I realized I did not need a god after all, to “Stand on Zanzibar” to “The Sheep loook” by Brunner, to “Bug Jack Barron” – most of them were published in a single imprint by a single publisher dedicated to this kind of sf, and it made very easy to search for more titles.

And I still remember how I simply stopped reading sf when everybody started to write about cool guys in mirrorshades as if that was somewhat “edgy”… cyberpunk was to sf what D&D pap was to fantasy…

But thinking about all that, the big question is.. how the hell I was able to find the time to read all that? At an age when I went to school every morning?

LikeLike

I definitely should have mentioned Pangborn, not for completism but because of his influence on me at about 12-13. Davy is a completely underrated book, and one of the grimmest things I believe I’ve ever read yet written in the most gentle, sensitive tone.

LikeLike

The “The Sheep loook” was obviously “The Sheep Look Up”, and I don’t know how that title got so mangled in typing. I blame my keyboard.

LikeLike

The piano has been drinking, not me.

LikeLike

Here’s a name that was oddly important* to me from this time frame: Andre Norton. I recently attended an SF convention themed “Women of Wonder”, intending by the theme to bring focus on women in the field. No mention of C.L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Vonda McIntyre, Alice Sheldon/”James Tiptree”, Evangeline Walton, Andre Norton … .

I want to say so much, except I don’t know what it is I want to say. All I will say is “Ron, you successfully re-conjured the excitement.” Now you’re going to move on to all that comics stuff I missed, so my excitement will remain … unrelieved. Again I say, .

At least I have “a whole post of crazy talk” to look forward to!

*I haven’t re-read her since I was maybe 20, but I DEVOURED those Witch World/High Hallack books – the ones written in the 60’s and 70’s, anyway. Helped that they were in the local library!

LikeLike

(Apparently, typing the word “sigh” surrounded in angle brackets is a bad idea. So where my post looks strange, insert a sigh and everything will make sense. Maybe.)

LikeLike

I never enjoyed a Norton book. Every one I tried seemed to me, afterwards, as if I’d just worked my way through so many blank pages.

Whereas Lee, for instance, is almost always either wonderful or “dammit she’s doing haiku again,” like a lot of the British authors – i can appreciate that she’s doing something each time. And Moore, Brackett, Sheldon, and many other women are simply top-notch authors with voices, topics, styles, and so on which lead me to say the male/female distinction in SF is not a matter of content whatsoever.

That includes beta level too, like McCaffrey and McKillip, both of whom have that odd “who? what happened? is there a plot? is this art? no I think it’s blah actually” quality in which I finally realized I was investing in the cover art alone.

I have not returned to Norton either. Perhaps we should both try a given title (again) and see what we think this time, respectively.

LikeLike

Dammit the computer decided to reconfigure right in the middle of writing that post.

1. I’m too weary to be appalled at the absence of women in SF in the panel on women in SFF, and – if I’m reading correctly – the added insult of calling it “Women of Wonder” in the apparent absence of knowledge about the anthology of that name. Did they even mention it?

2. I credit much of my SFF reading with my understanding that much men/women generalizing is confirmation bias, mainly because the writing can vary so thoroughly from amazing to awful, not only from author to author but within a given author’s range. It’s patently obvious that one can focus on the good work by, say, Philip K. Dick and simply write off the bad as “well that was a bad day” or “he did it for the money,” and then turn around and pillory Lee for her bad stuff and consider it to override her good work to the point of making it invisible.

A few years of listening to this, and to much ridiculous nonsense about trying to characterize “female SF” relative to “male,” led me to believe I was dealing with functional illiteracy and to stop paying attention to it. One of my few very good decisions in life. It doesn’t surprise me that ahistoricity is now added to it; it’s been clear to me for 25 years that most people in SFF fandom or criticism have read very little of it.

LikeLike

OK, let me be precise – it was this year’s Baycon (http://baycon.org/bcwp/). “Women of Wonder” was the overall theme, to a convention chaired (for the first time?) by women. It was well-intentioned, and sometimes touchingly delivered (seeing the Doubleclicks “Nothing to Prove” video with the director present was brilliant). They had posters throughout the convention with pictures/bios of important women in various fields – Science, Art, Music, etc. The … ahistoricity is EXACTLY the right word … of the “SF/Literature” poster appalled me. I actually put a “Who’s missing?” notepad next to the poster, added a few OBVIOUS names, and was pleased to see pages of additions from attendees before the end of the convention. Should have retrieved it on the last day …

Also, to your 2 – if the James Tiptree/Alice Sheldon affair didn’t teach SF fandom that lesson, probably nothing will (I really enjoyed _James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon_. There’s even a bit of CIA again).

On Norton – I’m tempted to subject us to _Quag Keep_, but of course no. Maybe something from the Time Traders (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Time_Traders) series? I’m not sure I ever read ’em, but a peek at the wikipedia entries reveals “Reds”, racism, and a “petty crook” hero.

LikeLike

I just wanna leave a place holder here for talking about Philip K. Dick, especially “VALIS,” which triggered a miniature schizophrenic reaction in me and apparently a few other folks as well over the years.

LikeLike

My Valis game: http://adept-press.com/games-estimated-prophet/estimated-prophet/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also: ROBOCOP. Here is my live-tweeting (or I guess live-posting) of Robocop when I remembered it existed, back in 2012:

“omehow TiVo taped the original Robocop, which came out in the late 1980’s when I was 12 years old. I practically worshiped this movie–I must have watched it three times in a row when it came out on VHS, and at one point I distinctly remember telling my dad, “Dad, I know you don’t get to see many great movies, but this is the greatest movie you’ll see all year.” He watched the whole thing with me and at last said, “Let’s hope you’re wrong.”

Anyway, it’s been like 25 years 😯 and I had completely forgotten this movie even existed. OMG it is pure 1980s awesome. Every scene makes me laugh at how ridiculous the 1980’s must have been to produce something like this. I was evidently alive through the entire 1980’s but remember almost nothing of popular culture. So Robocop is like a time capsule.

There are too many awesome parts to list, but here are some:

* The scene where ED-209 accidentally blows away some corporate stooge in the demo. Who uses live ammunition for a demo in front of your bosses? I guess it doesn’t really matter since nobody cares.

* The bad guy gang is classic 1980’s multi-ethnic. Black guy, Asian guy, “ethnic-looking” white guy, two other white guys.

* Everyone in this film has automatic weapons. One guy has a crazy-huge automatic rifle with an enormous side-loading clip somehow hidden under his trenchcoat.

* In a huge number of scenes, Robocop just shows up: no warrant, no probable cause, and starts blowing people away. The film doesn’t really dwell on the futuristic legal system that makes this possible. Also, everyone is really proud of Robocop when he does this, and in one scene they encourage school children to hang out with him.

* OMG he has the death robot just waiting in his office!!! Just straight chillin’ in the corner. “Marcy could you remove that potted plant, I want the death robot to go in that alcove. Thanks.”

* man!!! They spend a gazillion dollars developing this robot, and giving it missiles and shit, but nobody thinks, “Hey, can this thing climb stairs?” Or maybe in Delta City there will be no stairs, just ADA-compliant ramps everywhere…

* It cracks me up that “Uphold the Law” is RoboCop’s third priority.

* I’m a little baffled by the fact that when the police union goes on strike, they also let everyone out of jail. First of all, Corrections Officers are presumably a different union. Second of all: that’s a terrible way to get the public on your side. Third of all: in a future where criminals can apparently be shot to death practically on sight, surely it would be legal to leave them incarcerated until they starved to death (?), so why endanger the public and make more work for yourself again?

* Robocop is the best. This movie should be required viewing for all humans.

LikeLike

Robocop will be the topic of a superhero post for sure.

LikeLike

I just recognized those 3 coloring books. I had ALL of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

On the triumvirate: The dialogue in Foundation is puerile genre mash up. There is no dramatic tension in 2001, Rendezvous with Rama, or any of the novels. (I like some of his short stories). I still have a soft-spot for Heinlein’s juvenilia. They are designed to appeal to the pubescent male ego and they do it well.

LikeLike

I continue to wonder how the person who wrote the outstanding “I, Robot” stories, the interesting and influential The Caves of Steel, and the delightfully problematic (yes!) Lucky Starr books could have written anything that is otherwise published under Asimov’s name. I still don’t think I’ve made it past the first chapter of the first Foundation novel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Asimov was the author of the very first sf novel I brought (“The Current of Space”) when I was 11 years old so he’s probably the reason i started reading sf in the first place. And he had a quality that for years made him my preferred author (and that he later used in his not-fiction books): he was able to use paradoxes or scientific concepts in his stories as part of the plot (and not simply some technobabble in the background) but still be very simple and understandable, even for a 11-years old. I think that he was the first or among the first sf author for a lot of people for that reason (people who read first a novel by Phillip K. Dick or Delany at 11 probably would not start an habit of reading sf), and his mix of sf and investigative stories (like in his robot stories) had a very big influence on “what sf is” at the time.

When my reading skill improved I started liking other authors more, then I started liking his works less, and after years I simply stopped buying his books. I have never re-read them, probably fearing to discover that even his earlier books were not so good as I remember them.

So, even if I stopped buying his books, I have always a soft spot for him: he was the author who made me discover not only sf, but even that “adult” books (any books that was not marketed for children) could be fun, no matter how hard school was trying to convince me that they were boring and to be avoided at all costs

LikeLike

Reading that you spent your youth trying to become Harlan Ellison, I thought, “I spent my youth trying to become C.S. Lewis. Thank God neither of us succeeded!”

You probably came closer than I did though. 🙂

Oh, and my quest ended in exactly the same way: “I realized that he was simply a human who had perfectly understandable limitations in every way, and that I was already more like what I wanted to be than he was.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

(footnote: despite living in a context much more full of C.S. Lewis than Harlan Ellison, I *did* manage to read some Ellison, Zelazny, Tanith Lee, Robert Silverberg, and others, thanks to some friends of the family who lived more in *that* world than in the dominant culture of the region, and close friend who was a ravenous devourer of every damn piece of speculative fiction in the world and foisted books upon me.)

LikeLike

The question is whether I improved my life in any way by doing this. I can think of some ways maybe. Growing up/out of this outlook may have been made easier in knowing that he was Synanon-trained and therefore didn’t have ineffable powers of insight or that his verbal dominance skills relied on razor-sharp unswervable logic, merely that he was Gaming people outside of an agreed-upon and mutualistic Game.

LikeLike

Huh! That kinda explains a lot, the Synanon thing, I guess.

I think it would be asking a lot of most teenagers *not* to fixate on somebody as a guide to who they want to be. Some people just do it different ways than others. I asked a friend about this last night and he said his guideposts were protagonists from 80s movies, like Marty McFly and Danny LaRusso, which is a whole nother kettle of fish.

LikeLike

Quick correction: Jorge Luis is his name, Borges is his last name.

(And just because you might find this interesting, in case you didn’t already now, he and others like him who did “cuentos fantásticos” -Adolfo Bioy Casares, Julio Cortázar- are labeled “magical realism” in English-speaking sites like TvTropes and Wikipedia. I don’t know the historical reasons for this: to us, Cortázar, Bioy Casares, Borges, and also Poe and Lovecraft, all are “cuentos fantásticos” -not “fantasy”, of course; we understand Tolkien and Conan-. Then again, we all “know” Poe and Lovecraft are “horror”, and Borges, Casares and Cortázar are not… I dunno. Anyway, my point is that García Márquez and others’ -Isabel Allende, I guess?- “realismo mágico” feels like a rather different beast.)

LikeLike

Hi Santiago, I know the author’s name well; that’s a typo.

I share your uneasiness with the terms. I’ve never really liked the term magical realism in literature, because it strikes me as a compromise in a distinction that I don’t think really exists. The distinction is between “serious fiction” and the lower or vulgar category of “fantasy,” which I suspect is entirely driven by U.S. publishers in the mid-20th century. Then when it’s impossible to pretend that the author isn’t using fantastic techniques, but you don’t want to damn him or her, you call it magical realism instead of fantasy. But that compromise doesn’t work because I’ve seen it used in literary reviews as a derogatory label.

Whereas the fact is that many, even most authors include fantastic or semi-symbolic material in many of their stories, and the only period I can think of when some consistently don’t, is the same period during which this distinction was imposed by publishing and distribution categories. To me, Borges writes powerful and engaging literature, and whether he uses fantastic or wildly imaginative techniques in any given story is just that, a technique.

LikeLike

Pingback: Blog Watch: Forbidden Knowledge, the Letter of the Law, Owl Bear Variants, and Formulaic Genre Writing | Jeffro's Space Gaming Blog

Pingback: Gone ape indeed | Comics Madness

Pingback: Your mama’s apocalypse | Comics Madness

Pingback: Scary war | Comics Madness