Sheba knows her daddy

I can imagine the senior editor logic easily, upon seeing the mid-late 80s Suicide Squad pitch: “hey, the fans evidently want raw meat, Marvel’s massacring mutants, we have all these useless and unmarketable villains lying around, might as well blow’em up, one by one, or two by two if the plot needs it.” Oooh, awesome, here’s a fictional context for using them as cannon fodder so we can enter the “we’re gritty too” body count competition.

I can imagine the senior editor logic easily, upon seeing the mid-late 80s Suicide Squad pitch: “hey, the fans evidently want raw meat, Marvel’s massacring mutants, we have all these useless and unmarketable villains lying around, might as well blow’em up, one by one, or two by two if the plot needs it.” Oooh, awesome, here’s a fictional context for using them as cannon fodder so we can enter the “we’re gritty too” body count competition.

But they were dealing with John Ostrander, who liked these characters and knew this meant license to up the game on their sophistication or do awful things to them or both, and the opportunity to showcase short stories with any imaginable ending (personal favorite: Shrike’s “I’m-a comin’, Jesus!”). Even better, given the longer context for not always going for the quick splatter or laugh, and you have all the room you want for social commentary, meta-commentary, and drama. It’s the latter I want to go with here, because the internet’s full of “yeah that’s the title where they kill everyone, so cool,” and frankly that’s missing what this thing really does, for 66 issues as well as a few specials and a mini-series or two.

One of my categories at the blog is “Lesser is still great,” for which the flagship post is Second-best villainy. Imagine a title which paradoxically brings half a century of at-best beta villains into your hands in hordes, and says, “do whatever.”

It took a while to hit the full stride. The first phase, especially the first year, featured a lot of heroes by any other name and focused on their views and problems: the Bronze Tiger, Vixen, Nemesis, and especially Nightshade and the main character, Rick Flagg. Deadshot and Duchess (not her real name) were probably the only straight-up bad guys they planned to keep around.

It’s not too hard to tell who mattered just from the central platform motif.

This gets changed up hard, although gradually. During the second year and just after, they got rid of most of the heroes, traumatized and scaried up the ones who remained (Nightshade at first, then notably the Bronze Tiger and Vixen), and finished up the standing arcs with only one possible outcome, e.g. the Enchantress. Most importantly, the creators had discovered and fell in love with the best anti-villains in comics, Deadshot, which the creators expected, and Captain Boomerang, which they did not. Go figure.

Nightshade, Flagg, and Nemesis are very soon to die/leave at the publication of this image.

They also beefed up the rock-solid bad guys who worked best and settled in to enjoy them, like the Duchess (did I mention, not her real name?) and Ravan, and turned nonsuper supporting cast into protagonists: Amanda obviously as was the case from the start, but they also phased out Simon and Marnie in favor of Flo and Father Cramer.

Ah, now there we go – not a designated good guy in the bunch, and Deadshot would soon return too.

By this point the plot became … unpredictable, and the semi-changeable cast was the least of it. It’s a case study in the maturation of a comics title and the ability of determined creators to overcome the juvenile marketing that had greenlit it. It went full-bore Spy and turned the Squad’s own bureaucracy and political support into its worst enemy. It’s not about “gee who’s gonna die this time” any more; it’s about what kind of world uses felons as expendable black ops agents – and which of the principals thrive in that environment. Although I do not mean “thrive” in the therapeutic sense.

Real-world politics had been included since the beginning, and better than most comics of the day, but it was a bit lightweight in any other terms: some Soviet glasnost-y drama and drug war stuff that provided some context regarding U.S. demand for coke. But I think it was the eventual outcome Iran-Contra scandal that lit a fire of blazing dissent, for the first Gulf War and the interesting events in something we used to call the U.S.S.R. were ongoing, consequential contexts, not merely one-off devices. The stories didn’t handle any of these gently, instead taking a subversive turn which I am convinced was not scuttled mainly because the editors weren’t bright or informed enough to understand it. Frank showcase and dialogue about gay characters, phrases like “I am fat, black, and menopausal” issued as an effective threat, were par for the course. I can’t think of any other title ballsy enough to outright massacre a drug-running ring (no hand-wringing this time), re-tool the group Jihad to be politically understandable, to go after Oliver North with a tire iron, even referencing him outright, and eventually upping it to critique Zionism. It resulted in the complete destruction of any idealism which remained from the book’s initial pitch of “die for your country.”

Readers of the blog will recognize this as my catnip, and won’t be surprised that a lot of these will set up future blog post topics, similar to A thousand years more, O Kali. You can bet on seeing one about its strongest character, whom I haven’t named in this post and who is not present in any of the promo line-ups pictured above. This one is about another, also excellent character, also not pictured in the group shots, despite his vehicle playing a major role in many, many Squad fights.

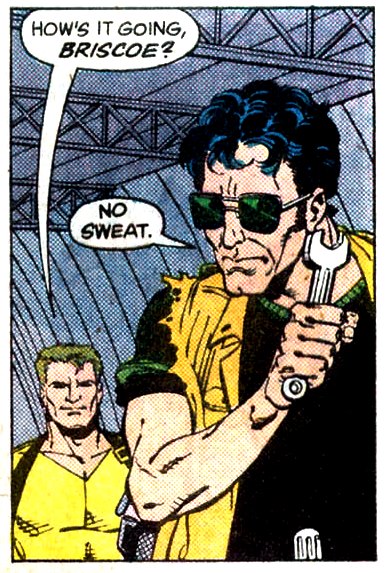

“Oh, well, he’s just a pilot – a utility guy, right?” No, that would be whatsisname, the Belle Reve security guy they kept trying to characterize without success. This is Briscoe. His copter, Sheba, shows up on the cover of many issues and soon, Briscoe showed up more and more in the pages, sometimes merely there in the background, sometimes with a pithy comment … and before the book’s first year was over, shown clearly to be out of his fucking mind.

See, Sheba is his daughter, or rather, was – we never find out when or how she died – and he’s named the copter after her. It’s not like her soul is possessing it or anything like that; it’s just a helicopter, albeit a terrifyingly maneuverable and weapon-equipped one. Which he sleeps in. Briscoe would be a plain old utility character except that he’s flatly one of the most insane people in the title, which puts him in fair running for mainstream comics as a whole.

Briscoe gave weight to the book, and I submit, its initial real weight. Only after this point did Deadshot’s particular problems, for example, develop from snarky characterization into something strong. Because Briscoe is not comics crazy, i.e., geek crazy. Geek crazy is fun. It’s a personality trait like “grim” or “uses big words” or “is over-precise with math.” It’s when a passenger in the vehice says, “You’re not well!” after the pilot performs some loop-the-loop and the pilot flashes a happy grin. Briscoe never does that whole “crazy enough to try it and good enough to do it” schtick. Nor does he show that somehow “underneath it all” he had some plan, or that he values his fellow Squad members “through the pain.”

Geek crazy overlaps with Hollywood mental illness, which uses clinical terms in specific but completely fictional ways to set up dramatic situations, usually to be resolved by the Power of Love. Examples include so-called “split personality,” often mislabeled schizophrenia, originally actually called schizoid personality, now folded into the larger category of multiple personality disorder; schizophrenia, usually romanticized into some form of genius, which they do with autism too; and amnesia, which is absolutely nothing like what you see in the movies. There’s also the vaguer, unlabeled manic pixie with quirky wisdom thing.

I accept all of these as dramatic devices, although I’m a bit tired of their use in lazy plots and cheap geek buy-in. But in reading Suicide Squad, the above panels leaned me forward hard. To be meta for a second, you can even see Speedy try to talk to Briscoe like he’s geek crazy, and get the response that lets you know, no, that’s not what he is. He is straightforwardly, clinically pathological. He needs to be a patient somewhere, getting real help. It’s wrong of the Squad to use an ill person like this, particularly for the stupid games its administration tends to play.

Writing characters like this takes guts. It’s not like riffing the tropes – crazy-reckless, manic pixie, socially-awkward computer mind – which reliably goes down onto the page and reliably flits off it into the reader’s comfort zone. If you try it, you either make it work way over the expected quality standard, or it’s terrible, unreadably bad.

Suicide Squad rose above its red meat premise, the “who’s gonna die today” arena, in a lot of ways. Briscoe led the way. He also showed the way through – in agony, torn limb from limb while still alive, yet screaming in grief and fear because he is watching the same thing happen to his daughter.

There’s nothing throwaway or black comedy about it.

Links: The many deaths of the Suicide Squad

Next: Plastic or fantastic

Posted on February 28, 2016, in Lesser is still great and tagged Briscoe, DC Comics, John Ostrander, Kim Yale, Luke McDonnell, mental illness, Sheba, Suicide Squad. Bookmark the permalink. 7 Comments.

I must confess that I saw the (probable) pitch behind the title that you cite on your first paragraph… and stayed far, far away from Suicide Squad. I don’t think I have even read a single page, ever.

(it happened with a lot of other Ostrander titles you had cited in this blog, too… he was probably too good at masquerading his titles as “another one of these grim and gritty comic books”…)

LikeLike

I think you’d really enjoy it, especially after a certain crucial change in the Squad’s field leadership.

LikeLike

Moreno, I started reading it on Ron’s recommendation. I lost steam after a Special Batman Guest Star appearance in issue 10, but the series isn’t bad by any means. It’s well written with good characterization; the art isn’t spectacular IMO but succeeds at visual storytelling. I definitely intend to go back to it, and might tonight, especially with the knowledge that after the first year or two it picks up.

LikeLike

The first year and a half is decidedly beta in comparison to the rest, but since they draw well on the earlier stuff, it’s hard for a long-time reader like me to distinguish the boundary. There’s a significant editor shift somewhere in there, can’t say exactly when. I think McDonnell’s art takes a quantum jump with the Deadshot mini-series and with Kesel’s inks, and suffice to say that the authors agree with you about who’s annoying and who’s not – and take steps.

LikeLike

Yeah, actually, it’s already getting better toward the end of the first year. Just got to the spot you quoted.

Part of my problem is that I don’t know DC material *at all* so some of the stuff that’s meant to carry weight falls a little flat for me. It’s the curse of growing up a Marvel zombie, I suppose.

LikeLike

Pingback: Two women | Comics Madness

Pingback: One twist of the wrist | Comics Madness