Everyday religion

First things first: never mind “belief.” I’m talking about upbringing, expectations, habits, and unconsidered identity, and about the real-world, utterly political history of institutions and communities. It’s really hard to get people to reflect upon or admit to ‘religion’ at this level (which is to say, to self-recognize), so I’m not going to bother as far as the reader is concerned – only to say that to a third party, you are really obvious along these lines.

First things first: never mind “belief.” I’m talking about upbringing, expectations, habits, and unconsidered identity, and about the real-world, utterly political history of institutions and communities. It’s really hard to get people to reflect upon or admit to ‘religion’ at this level (which is to say, to self-recognize), so I’m not going to bother as far as the reader is concerned – only to say that to a third party, you are really obvious along these lines.

Now for another, equally unusual claim: In Four-color Christ Jesus, I mentioned that “America” is not only a religion, it is the religion, which is to say an imperial state religion, which is to say a system of education and raw power. The POTUS isn’t “like” a high priest, he is high priest and general of the Church Militant, both. Here, I’m saying that what we call religions, the community/institution identities I described above, named or not named, visible or invisible, particularly the Abrahamic ones, are all sects within this larger thing, the Church of America for which the domestic U.S., NATO, and presumed spheres like Central and South America and the Pacific Ocean, are holdings. As sects, they matter a lot simply because communities’ local means of socializing, organizing, and ritualizing matter to people, period. They also have “places” in the big Church, i.e., orthodox, heterodox, or heretical; embraced, tolerated, or persecuted. Internecine spats among the orthodoxies are adjusted via visible channels; heterodoxies jockey for influence and inclusion via invisible ones; hereticals try to become heterodoxies, to maintain local power without interference, to hide, or to survive being crushed.

I’ll do the hardest one first: Christianity, hard because it’s so various in terms of power. There’s the mainstream version comfortably ensconced as acknowledged orthodoxies (although they bicker over relative standing; Episcopalian has been the winner for most of the past 150 years), and there are lots of less-powerful and even heretical bits scattered all over using the same words. Here I’ll do it in two parts. The first is the less-powerful set, defined for present purposes as a more-present, more active or preachy Jesus in mainstream comics.

One example is the Friend in Ghost Rider, during Tony Isabella’s run in the mid-70s, whose final “reveal” as actual-Jesus was denied at the last minute by Jim Shooter. You can read about that here, here, or in plenty of other internet accounts. It’s obvious to anyone reading it that the cat was outta the bag already, though, and this is certainly one of the prominent appearances of the non-Right hippie Jesus I’ve written about a few times.

Then there’s Rick Veitch’s Swamp Thing Jesus during the 80s – I remember the famous cover controversy at the time, and you can read internet versions of the industry dust-up here and here. Again, it was scuttled by the editorship with not even a blink, because fuck you that’s why.

Then there’s Rick Veitch’s Swamp Thing Jesus during the 80s – I remember the famous cover controversy at the time, and you can read internet versions of the industry dust-up here and here. Again, it was scuttled by the editorship with not even a blink, because fuck you that’s why.

See what I mean? That’s outsider-Jesus for you: if he’s going to be in there, then most likely he’ll be in there, himself, characteristically hogging the spotlight and pissing off the management. And it’s the same if a person who self-identifies as Christian in any visible or ethically-consequential way is involved, as he or she is instantly saddled with the story-responsibility of representing whatever “real Christians” are to the creators, positive or negative. Worth remembering: unless it’s a bland, vague, disconnectedc, churchy Jesus or one that’s safely nailed to a cross, then real-world editors and publishers want no part of him whatsoever – that shit is by definition political dynamite.

Now for casual/occasional observance of mainstream Christianity, which is ubiquitous in American life but surprisingly absent in comics – until you understand that such sects are practically defined, socially, by pretending that they’re just “hats,” that “no one cares,” that it “doesn’t matter,” i.e., in comparison with the real loyalty to and belief in America – using those exact words, I might add. Therefore it’s tricky in visual media to use symbols like a casually-worn cross or a Mary on a lawn, because such depiction is automatically iconic rather than casual; the reader understandably assumes that it’s intended to be more than a detail similar to personal style in clothes or choice of car. I think that’s why we see precious little of main characters who identify mildly with some denomination of Christianity, even though it would seem merely ordinary, a matter of characterization and grounding, to know in what denomination Reed and Sue were married, or for a relatively un-ideological character of your choice to attend, say, a Lutheran funeral and know where to sit and how to act. It’s also why physical churches are so generic and Hollywood in comics, unless they’re played up as distinctly insane and villainous.

Chris Claremont’s writing is almost always grounded in real-world history for locations and cultural sense of “place” for the characters; it’s probably my favorite thing about his work, regardless of whether I disagree or agree with a given instance’s thematic content. His Nightcrawler is an observant Catholic, and I suggest, in a pretty ordinary way, not in the freaky scarification way that later comics and films have taken it. His Colossus constantly blurts “Bozhe Moi!”, although without any context except that one presumes Russian Orthodox, and I don’t remember, at least, any examples of observance. Too, for both characters, I can infer a hint of “religious Eastern Bloc suffering under the Soviet boot” which was a powerful propaganda motif of the time, but that is perhaps moving into too much inference, and certainly into symbolism, not my favored territory. I also wrote about Miller’s presentation of Matt Murdock in these terms in Irish rage, Catholic guilt.

Aside from Catholicism, though, mainstream Christianity in superhero comics seems nothing more than a faint backdrop and Hollywood blur.

I’ll do the hardest one next: Judaism, which is strewn with social bomblets at several levels for comics, especially Marvel. It’s fine as long as you don’t enter into any questions … anyway, I’ll set aside the very real meta, industry, and societal context for comics, as it’s seen much attention and there are many good books available, a half-dozen via Kaplan’s book’s Amazon page at the least; see also the series starting here.

I’ll do the hardest one next: Judaism, which is strewn with social bomblets at several levels for comics, especially Marvel. It’s fine as long as you don’t enter into any questions … anyway, I’ll set aside the very real meta, industry, and societal context for comics, as it’s seen much attention and there are many good books available, a half-dozen via Kaplan’s book’s Amazon page at the least; see also the series starting here.

I’ve also already written about the textual and thematic Zionism of the X-Men and/or Magneto, textually and thematically (Today is for taboo, Today is for taboo 2, Today is for taboo 3). Further reflection along those lines is available via the character Sabra, and as this website eloquently demonstrates, there’s a perceived difference between being “a Jewish hero,” which in that perception is aligned with Israel as a state, vs. “a hero who happens to be Jewish.” This (my) post goes the latter route to think about Judaism in the X-Men and any other title.

Claremont is again the first author that comes to mind, with of course Kitty Pryde as everyday Jewish woman, the best rep for my lead image in this post. Now, it’s a little hard to find examples which are not explicitly identifying her Jewish identity with Marvel mutant-dom in the context of rabid prejudice, but I recognize that this was part of the point too.

Kitty’s important because she was created and presented as a Jewish person from the get-go. That’s a big contrast with the more symbolic, analytically-identified, and subject-to-debate examples. Superman is cited by many authors as an example of Jewish identity and aspiration in a character who’s not so designated, but coded to a noncontroversial extent (see Superman is Jewish? by Harry Brod). So may be Peter Parker, in exactly the same way; Kaplan’s book pictured above presents this case. Ben Grimm is a trickier case of a character who, like these two, is certainly identifiable with his Jewish creators, specifically Kirby, and maybe with some aspects of Jewish myth, but was not so designated, yet was never not so designated (whereas Superman and Peter are patently not, in literalist in-fiction terms) … so whether identifying him as Jewish in 2002 was recognition or retcon may be left to lit crit.

The thing is, whether for the iconic/symbolic examples or the real-person ones, comics Judaism always strikes me as so … generic. Essentialist, even: Jewish as a set, embedded quality. A Jew, period, on/off, is/not. But life’s not like that at all. In the U.S., for instance, Orthodox, or Conservative, or Reform? Or for that matter, as Jeannine Girofalo’s character puts it in Casa de los Babys, going further down the line to Unitarian, secular humanist, and giving up entirely?

I’m not being snarky. Being “Jewish enough” is a painful, pointed issue in the U.S., and one’s participation in local practice, or not, contributes greatly to life-decisions like marriage partners and to family tensions/ties. Tensions can push a person into the position of not participating in one’s home community’s practice because its members don’t regard one as “really” Jewish, but also of being regarded as profoundly Jewish when participating in some other non-Jewish, politically-progressive practice. It seems nothing more than reasonable to position a character who identifies as Jewish somewhere in such interactions, without any disrespect, insofar as we’re holding up the Marvel ideals of (1) the character’s personal life being plot-relevant and (ii) depicting real-world locations and activities. To put it right into focus, does Kitty’s synagogue include a female rabbi? A gay cantor?

I’m not being snarky. Being “Jewish enough” is a painful, pointed issue in the U.S., and one’s participation in local practice, or not, contributes greatly to life-decisions like marriage partners and to family tensions/ties. Tensions can push a person into the position of not participating in one’s home community’s practice because its members don’t regard one as “really” Jewish, but also of being regarded as profoundly Jewish when participating in some other non-Jewish, politically-progressive practice. It seems nothing more than reasonable to position a character who identifies as Jewish somewhere in such interactions, without any disrespect, insofar as we’re holding up the Marvel ideals of (1) the character’s personal life being plot-relevant and (ii) depicting real-world locations and activities. To put it right into focus, does Kitty’s synagogue include a female rabbi? A gay cantor?

Finally, saving the hardest one for last, Islam. Perhaps the very image of the conundrum of whether one’s religion is acceptable as a sect of America, because …

- Socially and historically, the demographic is mildly socially conservative, middle-class professional, community-minded, and quietly but firmly patriotic, adding up to perhaps the single most successful assimilation into U.S. culture on record. In fact, rather than excelling in some specific sector and bottoming out in another, the metrics line up almost spookily with national/overall ones.

- But in fictional presentation, the long-running history of immigration into the U.S. is ignored, depicted instead as secretive, foreign-minded, and unpredictably irascible fanatics with ancient, unreasonable grudges. And that’s before 9/11; since then, it’s been all about loyalty tests and the unshakeable stereotype that beneath the mild exteriors of, say, a suburban dentist or a business student lies a hidden core of explosive, to be set off who knows how after contact with who knows what.

I wrote about the unnecessary and potentially toxic perceived-dichotomy between Good Muslim / Bad Muslim in Jihad, exclamation point optional. Here I’ll put it into harsher terms: that Islam is perceived by a substantial fraction of the U.S. population not merely as heretical to the Church of America, but heathen – with all connotations of “inhuman” and “savage” and “beknighted” as you may think. The only choices for a heathen, whether individual or community are simple: convert now and demonstrate it repeatedly, be forever crushed into slave status, or die. Showing oneself to be a “good American Muslim” may be a matter of life and death, and philosophical questions of whether it is good to submit so wholly to Imperial America may wait for those with less on the line.

I wrote about the unnecessary and potentially toxic perceived-dichotomy between Good Muslim / Bad Muslim in Jihad, exclamation point optional. Here I’ll put it into harsher terms: that Islam is perceived by a substantial fraction of the U.S. population not merely as heretical to the Church of America, but heathen – with all connotations of “inhuman” and “savage” and “beknighted” as you may think. The only choices for a heathen, whether individual or community are simple: convert now and demonstrate it repeatedly, be forever crushed into slave status, or die. Showing oneself to be a “good American Muslim” may be a matter of life and death, and philosophical questions of whether it is good to submit so wholly to Imperial America may wait for those with less on the line.

I’ll focus on the tricky detail of visual observance. This is a perception problem for all religions, in that it’s taken to be an indicator of belief or, for that matter, unreasonableness, but only regarding religions besides one’s own. Given that Islam is itself wrestling with a good/loyal vs. bad/dangerous narrative, specifically regarding acceptance into America, that question is cast into bizarre shapes. Real or not real, and is that good or bad? (You may point out that this is especially trenchant in Europe, but I submit that “Europe” has been a fiefdom of Church America for some time now.)

I’ll focus on the tricky detail of visual observance. This is a perception problem for all religions, in that it’s taken to be an indicator of belief or, for that matter, unreasonableness, but only regarding religions besides one’s own. Given that Islam is itself wrestling with a good/loyal vs. bad/dangerous narrative, specifically regarding acceptance into America, that question is cast into bizarre shapes. Real or not real, and is that good or bad? (You may point out that this is especially trenchant in Europe, but I submit that “Europe” has been a fiefdom of Church America for some time now.)

Cue our new Ms. Marvel, Kamala Khan, who – based on my limited exposure and on what I’m seeing online – is a fun, engaging, and intelligently-written character. I don’t intend to put down any of those things by observing how well she conforms to the “good Muslim” of the Church of America: acceptably heterodox, not heathen. The first concern being that she is not Arab, which was deliberately averted (see here), and which I suspect would have been a non-starter. Even as is, cue the careful attention to whether she does or doesn’t, should or shouldn’t, wear any ethnic garb. Such questions stay with the simplistic notion of clothes=belief=intransigence. Therefore, unsurprisingly, and completely consistent with the good/heterodox, “now you must live up to it and us” model, accessories are well and good, but not outfits. It’s not just about hijab, either; I note in passing that nowhere in her costume do we see the color green.

Cue our new Ms. Marvel, Kamala Khan, who – based on my limited exposure and on what I’m seeing online – is a fun, engaging, and intelligently-written character. I don’t intend to put down any of those things by observing how well she conforms to the “good Muslim” of the Church of America: acceptably heterodox, not heathen. The first concern being that she is not Arab, which was deliberately averted (see here), and which I suspect would have been a non-starter. Even as is, cue the careful attention to whether she does or doesn’t, should or shouldn’t, wear any ethnic garb. Such questions stay with the simplistic notion of clothes=belief=intransigence. Therefore, unsurprisingly, and completely consistent with the good/heterodox, “now you must live up to it and us” model, accessories are well and good, but not outfits. It’s not just about hijab, either; I note in passing that nowhere in her costume do we see the color green.

Do you think you’ll see Kamala standing up for herself like Kitty did in the panel depicted above, using the equivalent and very real-and-recent events which would warrant it? Identifying her ethno-religious identity with an incontrovertibly, even brutally realistic moral position – facing down people who historically would have held the mainstream counter-view? Positive-thinking says, “why yes! That is essentially happening already and will become similarly explicit perhaps next issue!” Bad Ron growls and opines that that day is a long way off. Maybe decades, as long as her role as “good little American Muslim” is sustained as her marketing point. Maybe never.

I grant you this development is much to be preferred over treating Muslims as inhuman heathens, which has been done quite a few time in American comics, Marvel and otherwise. But stay with me in at least being a little suspicious of assimilation as a form of submission. Go back and look at that picture of Sabra; click around a bit on the net to learn more about the character. Now … work with me here … ask yourself how a Pakistani national-unity superhero, drawn similarly regarding ethnicity, flag, et cetera, would code to you, by contrast. Our new Ms. Marvel is not a Pakistani citizen or resident, so that’s not quite what I’d ask you to imagine for her, but I suggest she’s visually built specifically not even to hint that way. Fascinating: Sabra is nationally/state iconic as a deliberate creator’s choice, whereas Kamala is non-nationally/state iconic because there isn’t any other choice.

At the risk of having an opinion, my reader’s wish is to get away from the iconic and into the everyday, for religion as well as all other cultural signifiers. I’m thinking of specific denominations that make sense geographically and historically, personal experiences which position a character relative to the upbringing and context, and life-choices being made which others find surprising or unsurprising on that basis.

Let’s think about this: what religion were the following Marvel supervillains raised in, to whatever degree of observance, and what might they practice or at least feel attuned to now? Doctor Doom, Doctor Octopus, the Kingpin, Lex Luthor, and the Green Goblin, focusing on the late Lee, early Thomas stage – about 1970.

When a reader’s wish is strong enough to be presented out loud, the only thing to do is to transform it into a writer’s act. So I’m putting it into practice with Adept Comics, drawing hard on personal experience and encounters.

The characters in One Plus One are both nominally Roman Catholic but in weird, geographically-specific ways. Topaz is Tex-Mex brought up to assimilate, for whom the Church is hardly noticeable. She thinks of it entirely as a subset of being American and hardly ever observes, to her mom’s disapproval. However, unconsidered habits and values matter to her – it wouldn’t even occur to her not to be buried in a Catholic cemetery, and she knows what to wear on this-or-that holiday.

The Bandit is Polish-American and his mom was raised in the Church in Chicago, but then she dramatically lapsed – which as far as I’m concerned is a whole sect of that denomination – and moved to the west coast when he was little, where he received zero instruction or observance. He was involved with a now-extinct hard-Left Christian group as a young teen and has a soft spot for Liberation theology efforts. As an indicator of what I’m talking about, he viscerally dislikes Mother Theresa and can tell you why, but never reflects on why he takes it personally.

For the Arab-American main character in Sword of God, well, you’ll just have to see for yourself in the upcoming story “Friends,” where it’s a major plot point, but for now, you should know the most sincere religious person in the story – and also the most patriotic – is the Muslim FBI agent he stuns on page 1 of “The Edge.”

Next comics: Sword of God, The Edge, p. 9 (September 20); One Plus One, Two, cover page (September 22)

Next column: God, an aardvark, and a man between (September 25)

Posted on September 18, 2016, in Storytalk, The great ultravillains and tagged Arie Kaplan, Ben Grimm, Casa de los Babys, Chris Claremont, Christianity, From Krakow to Krypton, Ghost Rider, Harry Brod, hippie Jesus, Islam, Jesus Christ, Judaism, Kamala Khan, Kitty Pryde, Ms. Marvel, religion, Rick Veitch, Superman, Superman is Jewish?, Swamp Thing, The Friend, Tony Isabella, Vincent Brook, X-Men, You Should See Yourself, Zionism. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

The examination of “Religion, minus Belief” seems really useful to me – while belief hasn’t been an important component of my personal interaction with religion for a LONG time, I continue to learn things about both small details (why my in-the-heartland-of-East-Coast-Episcopal church was built in Spanish Mission style) and macro-trends that mattered in ways I never knew (Anglo-Catholicism? I never heard of it, but it explains SO much that mystified me).

Add to that America-as-religion, and the interaction with comics – particularly your own in-progress work, since my general comics-background is lightweight – and I think this post/these ideas should prove very interesting.

Oh, and this link (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/why-god-and-country-christianity-is-just-another_us_57e0324ee4b0d5920b5b32db) caught my eye, probably because of this post. Not EXACTLY what you’re talking about re: America (because the author – by my reading – remains very/primarily interested in belief). But very complementary/reinforcing, I thought.

LikeLike

Thanks! Among the many meanings (with ordinary names) that the word “belief” is used as a cover or mask for, is “commitment to action.” Particularly in a zero-sum context, implying that such an action necessarily abandons some other action, and opposes yet others.

Therefore when I say we are talking about politics, meaning policy, meaning actions which enforce actions/lack-of-actions on groups of people, then religion as institutions and communities is not merely “inseparable,” it’s synonymous.

LikeLike

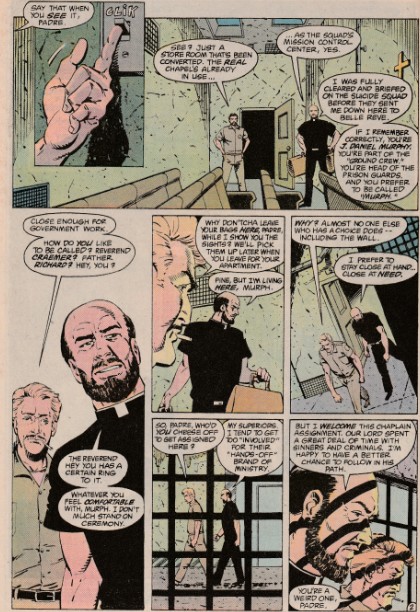

Shoot, I forgot to mention Father Craemer from John Ostrander’s run of Suicide Squad, later seen in his Spectre..

LikeLike

Also, adding this link: Erasure of the Muslim superhero.

LikeLike

rereading an old Marvel Two-in-One with the understanding that Ben Grimm was (probably) Jewish, I was struck when he suggested Bill Foster dropped the Black Goliath name for Giant Man, partly because “from what I remember in Sunday School, Goliath was a bad guy.”

Sunday School? Gruenwald and Macchio wrote the issue. I guess, as strong a Marvel historian as Gruenwald was, he wasn’t in the loop on the Jewish Grimm idea.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The issue of Ben Grimm’s religion – and not abstractly, but specifically, Jewish or not – seems very much to me the same as the “Doom’s face” one. It may not even be possible to discuss, given the various fixed ideas in place concerning, e.g., authorship, Kirby specifically, Judaism as an distinctly American identity, “is” in terms of character text, and much more.

LikeLike

also, it’s Janeane Garofalo. the vowels are a-e-a-e-a-o-a-o, which is helpful to know.

LikeLike

as is often the case, I’m only commenting when I seeing problems, but I’m enjoying your commentaries quite a bit. keep up the good work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Super good | Comics Madness

Pingback: Mustache match | Comics Madness

Pingback: Shine a Light | Comics Madness

Pingback: May 2023 Q&A – Adept Play