More women

I take no part in ostentatiously excluding Dave Sim and Cerebus the Aardvark from modern comics discussion, and I dislike the stink of piety that rises from it. “Are you now or have you ever been” regarding liking or valuing Sim’s work was instituted about twenty years ago and unfortunately seems to have stuck around. Before you snark “well he deserves it” at me, please consider that Frank Miller and Howard Chaykin have not only depicted but expressed vile (rather than “problematic”) gender positions, but also more consistently and with more widespread impact, I would say, than Sim. I see no comparable consequence for them, their readers, or developers of their material.

I’ll speak with a little insider knowledge at the time (for #186, fall 1994), regarding both the Cerebus fan community and a few comics pros. I think the exclusion is founded less on a specific feminist-or-simply-decent position than on seizing an opportunity to stand on the goodright-think platform for mutual gain. Much lies in the lap of Gary Groth, particularly back then before the internet had fully produced its panoply of opinion-makers, when The Comics Journal provided the sole pundit-status imprint for what one was supposed to say. To my knowledge no one has reviewed the step-by-step process of transferring Sim from comics champion to sparring partner to persona non grata, but I wish they would. It wouldn’t reflect favorably on the magazine.

I’ll speak with a little insider knowledge at the time (for #186, fall 1994), regarding both the Cerebus fan community and a few comics pros. I think the exclusion is founded less on a specific feminist-or-simply-decent position than on seizing an opportunity to stand on the goodright-think platform for mutual gain. Much lies in the lap of Gary Groth, particularly back then before the internet had fully produced its panoply of opinion-makers, when The Comics Journal provided the sole pundit-status imprint for what one was supposed to say. To my knowledge no one has reviewed the step-by-step process of transferring Sim from comics champion to sparring partner to persona non grata, but I wish they would. It wouldn’t reflect favorably on the magazine.

Regarding the intervening decades, anyone committed to comics scholarship has no excuse. In terms of pure art and design, Cerebus is simply one of the best examples of the medium in its history, and there isn’t a working creator alive today who isn’t directly or indirectly influenced by Sim and Gerhard artistically – and economically and professionally, even more so.

How about morally? Well, whose morality? Here, I’ll quote myself from an earlier post:

I do not highly regard the circular process of (1) using the comic as a lens/referendum on the guy, while (2) simultaneously using the guy as a lens/referendum on the comic. That’s lazy and thoughtless.

So never mind Dave Sim. I’m talking about the comic: the characters, how they’re depicted, what they say, what they do that affects other characters, and their roles in how things play out. Which also means, never mind what you think is right or wrong. I’ll take it to a real issue that does in fact matter to me, and let me put it crudely: are Sim’s women characters “cunts?”

It has a lot to do with the comic as a story. It’s ridiculous to accuse, say, Ranxerox of being awful because its female characters fit the bill (they do) – it’s Ranxerox for God’s sake, why else are you reading it if not for such things? For Cerebus, I’m going with the evident observation that it’s a novel, and a pretty serious one, in which the clashes of personalities and goals and circumstances produce some real outcomes. In that context the question stands.

I don’t like her or she’s a bad person are not criteria, nor is using one’s sexuality in a mean or disagreeable way. Enough male characters fit that bill to turn it into a “degrees of” argument, and then into a “degree of each degree,” which is no use. The same applies to standard stereotypes for minor characters which are very common and cover just about any mid-20th-century North American humor you can name; I don’t see a reason to distinguish in gender terms between sending up Mrs. Henrot-Gutch the harridan mother-in-law vs. Filgate the New York Italian jumped-up hood, or the obese-devout chambermaid vs. Boobah the gluttonous idiot. Same as well to parodying public figures like Margaret Thatcher or Keith Richards.

I’ll set some criteria:

- One-dimensionality, meaning, no reflection and flexibility

- Identifying femaleness or female anatomy with stupidity, weakness, or evil

Take it to the tape.

Church & State

I’m considering this story (#51-111) in isolation, as it’s the linchpin for all plot events in the full 6000 pages. From the larger perspective it’s the first major clash among multiple conspirators from various levels of political power and reality, but from the protagonist’s point of view, it’s driven by his interactions with four women: Michelle, Red Sophia, Jaka, and Astoria. Cerebus is interesting insofar as each woman finds him interesting, whether as representing a given power-interest, or on a more personal basis. I also think that the personal basis turns out to be the more important component in each case. Here’s where each woman is present and active along the sequence of events.

- C&S 1: Cerebus is manipulated by Michelle and Weisshaupt into marrying Red Sophia and becoming prime minister again, this time under Weisshaupt’s guidance rather than Astoria’s

- C&S 1: Cerebus becomes pope and wrests actual power away from Weisshaupt

- C&S 1: Red Sophia leaves him; he also rejects (or is denied) escape from the situation with Jaka

- He’s then is ousted by other power-seekers; intimations begin that more is at stake here than merely a political position

- C&S 2: Astoria re-enters the story seeking to take control at a metaphysical rather than political level, but Cerebus outmaneuvers her and recovers his pope-hood with Michelle’s help

- C&S 2: Astoria is arrested for heresy and murder, and among a complex series of events, Cerebus rapes her; amid her trial and much metaphysical upheaval, the Great Ascension begins

The most evident power-player among these characters is Astoria, but it’s hard to distinguish among character development, revelation of back-story and depth, and re-invention for purposes of a new storyline. In the preceding volume, High Society, she was a political manipulator and nearly-pathological liar who took over control of the Roach from Weisshaupt and supplanted Weisshaupt as Cerebus’ primary handler. It”s eventually revealed that her goal is women’s suffrage, treated with astonishment by the other principals.

Church & State provides a more complex back-story for her via some intelligence-gathering by another female character named Theresa, and the step by step revelation that Astoria’s been part of a revolutionary effort among the female members of the Church all along. (For non-Cerebus-ers, this effort is split between the Cirinists, the mother-conservatives, and the Kevillists, the daughter-radicals.) The details are complex but hinge on her disagreement with Cirin over whether “women’s liberation” does or does not include a pregnant woman’s authority over the fate of her fetus. She doesn’t take an active role until Part 2, much of which is very mysterious in the moment but is clarified later – suffice to say she clashes magically with Cerebus and is removed from the situation, but returns later having assassinated a powerful political figure, the Lion of Serrea, in the interim.

Run a search on “Cerebus Astoria” and you’ll get multiple hits concerning the rape in #93. Aside from Trina Robbin’s excellent analysis in the letters page at the time (reprinted in A Moment of Cerebus), what I don’t see in the internet summaries or discussions is the rapid-fire shifting of power between the two of them before, during, and after the act. Even as a beaten and chained prisoner, she initially confuses and dominates him as she’s almost always done, even removing her panties and taunting him with the bind between sex and his married-and-papal status. He then blindfolds and gags her, pronounces them married, rapes her, and pronounces them divorced.

Run a search on “Cerebus Astoria” and you’ll get multiple hits concerning the rape in #93. Aside from Trina Robbin’s excellent analysis in the letters page at the time (reprinted in A Moment of Cerebus), what I don’t see in the internet summaries or discussions is the rapid-fire shifting of power between the two of them before, during, and after the act. Even as a beaten and chained prisoner, she initially confuses and dominates him as she’s almost always done, even removing her panties and taunting him with the bind between sex and his married-and-papal status. He then blindfolds and gags her, pronounces them married, rapes her, and pronounces them divorced.

I don’t think the text supports a “she deserves it” reading. It’s not played for laughs. Cerebus is exerting his power over her just as he’d exerted it over Weisshaupt (humiliating, condemning, and indirectly killing him), very much in “you’re not the boss of me” wise. The fact that she’d been messing with him until then isn’t relevant to the basic brutality and purpose of the act. The majority of the text is her thought balloons, and she’s both humiliated and physically disgusted – and significantly, it doesn’t even work: she recovers her position in their battle for control soon afterward. More significantly, the content of the Great Ascension in later pages delivers an incredible “you are unworthy” message to Cerebus based precisely on his willingness to do this very thing.

To stay with the immediate text, this scene in the cell also includes the first display of her fanaticism, where it’s revealed that she’s actually the author of Kevillism and her goals, far from the mere policy reform of suffrage, include profound militant sexual revolution. But interpreting her intensity at this point is tricky, in that it’s tied up somehow with the “cosmic role” that she’s trapped in, or rather the pair of roles that gets played over and over, including flashbacks to herself as Pope and Cerebus as the principled prisoner.

That’s all part of the utter shake-up of the subsequent trial, the scene which redefines literally everything that’s happened in the series to date, and which provides the foundation for all the points I discussed in God, an aardvark, and the man in between.

That’s all part of the utter shake-up of the subsequent trial, the scene which redefines literally everything that’s happened in the series to date, and which provides the foundation for all the points I discussed in God, an aardvark, and the man in between.

Even as Cerebus tries his hardest to get out of sentencing her to execution, his historical or spiritual “role” to do so keeps taking over, and I interpret Astoria’s insistent martyrdom to be the same – and yet, they keep switching roles, hallucinating back and forth between historical periods, to the extent that when he does pronounce the sentence, he is her instead and bellows “Kill him!” to confusion of all present. And that’s not played for laughs either. They’re both shattered by the intensity of these imposed roles and the effort to resist them.

By contrast, Michelle at first seems to be a minor figure. She appears in considerably less pages and her back-story is much less detailed, but I submit she’s at least as significant as Astoria in story terms. In Church & State Part 1, she’s introduced first as “the Countess,” unruffled and unusually compatible with Cerebus’ unusual psychology and personality, privileged but far from naive. Her back-story implies her role as a cordial rival to Weisshaupt who takes care of the Roach now and then.

Her dialogue imparts a lot of important information but in the fashion of speaking to a listener already knows it, and much of that isn’t revealed for a long time. So many, many pages later, one has to go back and re-read to understand what she is saying about the Cirinists and Kevillists, Astoria, Sir Gerrik, and Cirin, and how many of the conflicts of Church & State, and later stories, lie in this tangled little web of sex, kin, and control.

Readers of Cerebus, feast your eyes on that a while. You’re welcome. (Bonus point: Sir Gerrik is never ever seen in the entire series and plays no active role off-panel. Bummer.) (Other point: minor inconsistencies in different characters’ dialogues have led to much fan circles-and-arrows epiletic tree building; I’m taking the other route and merely passing them over, so certain details of the diagram can be considered “fuzzy.”)

Readers of Cerebus, feast your eyes on that a while. You’re welcome. (Bonus point: Sir Gerrik is never ever seen in the entire series and plays no active role off-panel. Bummer.) (Other point: minor inconsistencies in different characters’ dialogues have led to much fan circles-and-arrows epiletic tree building; I’m taking the other route and merely passing them over, so certain details of the diagram can be considered “fuzzy.”)

Anyway, during this sequence, despite interruptions by an apparently-being-dumped boyfriend and the aforementioned Roach, she and Cerebus tentatively and rather honestly begin canoodling a bit, based – shock – apparently on genuinely liking one another. I enjoy this sequence for a lot of reasons, not least that the pages I’ve chosen come from three separate scenes, such that with each quiet interlude, the two of them get just a little bit more comfy as they hang out.

Anyway, during this sequence, despite interruptions by an apparently-being-dumped boyfriend and the aforementioned Roach, she and Cerebus tentatively and rather honestly begin canoodling a bit, based – shock – apparently on genuinely liking one another. I enjoy this sequence for a lot of reasons, not least that the pages I’ve chosen come from three separate scenes, such that with each quiet interlude, the two of them get just a little bit more comfy as they hang out.

Then the whole thing is borked by the spectre of Claremont inside the Roach’s head, who manipulates Cerebus into alienating her, and as it happens, he then falls directly into Weisshaupt’s manipulations and wakes up hung-over, mind-blown by some drug or other, and married to Red Sophia. (Keeping up, non-Cerebus-ers? Good luck …)

Church & State Part 1 goes on to Cerebus resuming the prime ministership, becoming the pope, rebelling against Weisshaupt and causing his death, and getting unceremoniously evicted from the papacy in a series of events too freaky to describe here. At the opening of Part 2, Michelle is briefly involved again, wryly helping the Secret Sacred Wars Roach who’s off anyone’s leash at the moment, and she carries out Weisshaupt’s dying request to help Cerebus regain the papacy.

She tells Cerebus some things: that she had been a set-up by or protege for Weisshaupt rather than a born-into-it countess; that she was grateful to Weisshaupt for seeing her educated, but that she despised his power obsession and his sense of grand purposes; and most importantly, that Weisshaupt had planned to set her up as Cerebus’ companion during the Great Ascension.

She tells Cerebus some things: that she had been a set-up by or protege for Weisshaupt rather than a born-into-it countess; that she was grateful to Weisshaupt for seeing her educated, but that she despised his power obsession and his sense of grand purposes; and most importantly, that Weisshaupt had planned to set her up as Cerebus’ companion during the Great Ascension.

This ties back to my points in God’s privy parts as well as the interesting notion that Weisshaupt had intended a male-female pairing for the Ascension rather than Cerebus alone. Also, as he’d originally planned to do it himself, I wonder who he’d planned on accompanying him?

The key point here is that she refuses to do any such thing and tells Cerebus this to his face.

Michelle is barely seen again throughout the rest of the comic, and never in a way which reveals her situation or fate. She is the first of three major characters who deliberately exclude themselves from the power-seeking, competitive situation, and who seem actually to leave the series, steering themselves clear of the author’s ability to affect them. Michelle is also the only one to do so specifically regarding her effect on Cerebus, deciding not to ruin his life or to let her life be ruined. Given that she also escapes the first in-story attempt at the Great Ascension, everything about how that event plays out and therefore, everything about how the story proceeds at all, for every other character, is profoundly affected by her decision. And yet I see no mention of her in any “what about women in Cerebus” discussion I’ve encountered.

Now for the romantic-interest characters, Red Sophia and Jaka, who in this same volume are respectively the one he gets stuck with and the one who got away.

Red Sophia’s famous earlier appearances were parody, case closed, just the same as the Prince Valiant character, and she’s never above delivering the occasional joke scene. In Church & State Part 1, she’s more interesting but still a bit of a goofball, including farcical wife-comedy. In an earlier dialogue, when she quotes him saying that all she ever wanted from the marriage was free privilege and comfort, she accurately responds, “Sure. Same as you.” Under the poofy hair, she’s quite reasonable, not demanding anything from him or clinging – he’s the whiny-needy one, not her. Bit by bit throughout Part 1 she gains in story stature, as the only person who’s not afraid of Cerebus after he becomes pope, perfectly capable of skewering his pretensions.

Without mysteriously transforming into a different character entirely, she shows judgment, dignity, and an admirable sense of humor in coping with a real insight: that Cerebus doesn’t and will never love her. And then shows that without pitching a fit or blaming or freaking out, she has decided that it’s not enough, implying that to her, the potential relationship was important after all. (I grant you that her brief appearance in Part 2 is nothing but low comedy.) (However, in a much later sequence, she reveals, heart-breakingly, that she did love the “inside” Cerebus who wasn’t evident to her mother, and defends her position despite public censure.)

Without mysteriously transforming into a different character entirely, she shows judgment, dignity, and an admirable sense of humor in coping with a real insight: that Cerebus doesn’t and will never love her. And then shows that without pitching a fit or blaming or freaking out, she has decided that it’s not enough, implying that to her, the potential relationship was important after all. (I grant you that her brief appearance in Part 2 is nothing but low comedy.) (However, in a much later sequence, she reveals, heart-breakingly, that she did love the “inside” Cerebus who wasn’t evident to her mother, and defends her position despite public censure.)

Talking about Jaka in Church & State is riddled with pitfalls, as she receives so much more attention and story-role or roles later in the series. It’s hard to dial back and understand that here, although she’s given more depth than in her earlier appearances, she has way less depth than the other three characters I’m talking about. I guess I have to explain that she played a comedic role in an early issue, which then became a more dramatic lost-love role for a scene back in High Society, and now Church & State brings a similar scene in which she’s shown to be married and pregnant, and thus Cerebus can’t “leave it all behind” and run off with her.

Talking about Jaka in Church & State is riddled with pitfalls, as she receives so much more attention and story-role or roles later in the series. It’s hard to dial back and understand that here, although she’s given more depth than in her earlier appearances, she has way less depth than the other three characters I’m talking about. I guess I have to explain that she played a comedic role in an early issue, which then became a more dramatic lost-love role for a scene back in High Society, and now Church & State brings a similar scene in which she’s shown to be married and pregnant, and thus Cerebus can’t “leave it all behind” and run off with her.

Therefore giving her role in this story its tragic, romantic bite requires some skillful play with previously-unseen characterization and memes, not least among them Jaka’s prodigious 80s bangs, rather than working from past content. Their closing good-bye waves induce you to bawl shamelessly, believing in the authenticity of their prior relationship, however undepicted. (Yes, you. Read it and see.) That it’s not merely a trick in the series’ larger scope should be evident a few paragraphs down.

Many, perhaps all good writers talk about their characters getting away from them, and I think it happens all the time in Cerebus. The series from 1 through 111 (the end of the Great Ascension) is a classic study of a great story emerging from a lot of improvised pieces – not least in the striking force delivered by these female characters.

Mothers & Daughters

Mothers & Daughters, #151-200, composed of almost evenly of Flight, Women, Reads, and Minds, is the mirror to Church & State Parts 1 & 2, similarly including a mystic confrontation with “the truth” at the end. I venture to say that just about everyone has read the text pieces in Minds and clutched themselves in horror. I’ll be weird and talk about the story instead.

Cirin – only glimpsed once prior to this point and revealed to be an aardvark – is now ruling the land with an iron fist, atop a religious and state hierarchy, pretty much exactly as Cerebus had always wanted to do, and just like him, she’s become obsessed with the next Great Ascension. Astoria’s languishing in prison – just as she was under Cerebus’ brief second tenure as pope – until she can finagle her way back into power, which she handily does. Much mystical and political drama later, at the beginning of Reads, both of them, Cerebus, and the mystic Suenteus Po, long a participant in the story but now physically present and also an aardvark, have come into confrontation.

Astoria provides a wealth of material in this story and it’s hard to confine myself just to the resolution – suffice to say that she demonstrates scary expertise over the abuse of the assumptions of sisterhood, and there’s a scene with a woman calling her out on her power-tripping bullshit which deserves a whole chapter in someone’s dissertation because Astoria is smart enough to know she’s right.

Astoria provides a wealth of material in this story and it’s hard to confine myself just to the resolution – suffice to say that she demonstrates scary expertise over the abuse of the assumptions of sisterhood, and there’s a scene with a woman calling her out on her power-tripping bullshit which deserves a whole chapter in someone’s dissertation because Astoria is smart enough to know she’s right.

It also turns out to be the door left open when, during the four-way confrontation, she realizes that all the power-seeking has been a wrong turn. That top half of the page takes my breath away – four profound, succeeding phases of emotion, culminating in serenity. It’s profoundly dramatic: until this point, she’s been the single most effective manipulator and conspirator of the series, not always successful, but always bouncing back and working her way to the top again. Even here she’s significantly ahead of both Cerebus and Cirin in her inside knowledge.

But she chooses instead to listen to Po, to decide she agrees with him, to regret some of her past, and to move on. Or rather sideways, choosing to take Po’s path and to set aside all power manipulations, because “because I can” is not enough. It’s the path already marked out by Michelle, who isn’t mentioned here but whose prior decision is stamped all over it.

But she chooses instead to listen to Po, to decide she agrees with him, to regret some of her past, and to move on. Or rather sideways, choosing to take Po’s path and to set aside all power manipulations, because “because I can” is not enough. It’s the path already marked out by Michelle, who isn’t mentioned here but whose prior decision is stamped all over it.

(Geez, that little catch in Cerebus’ voice … they may not like each other a lot, but these characters have history, and when she opts out, you can see a piece of him finding itself lost.)

Now how about Cirin, who at this same point in the story does absolutely no such thing, and instead, like Cerebus, doubles down on her determination to rule the world and to be the most important person in it. Cirin – I’ll call her by this name rather than her birth name, Serna – is at first glance the story’s essential villain to date. She’s ultimately at the center of everything that’s tripped up or blocked Cerebus since nearly the beginning, she has succeeded at everything he tried to do and reduced him to nothing, and she’s hidebound, authoritative, apparently humorless, and evidently plain mean.

… and in addition, through the series of events throughout these fifty issues, she’s deep as hell. Unfortunately no more reveals are forthcoming regarding Sir Gerrik, whether he was adopted, his father whoever he was, and Astoria’s maybe/not aborted pregnancy. But about the origins of Cirinism, geez. Serna’s history is obviously a whole ‘nother untold series: sidekick to a revolutionary, then she took over the movement via running its security, then took over her mentor and best friend’s actual identity, to set up a reign of thought-control as scary as it’s impressive. And yet she’s not wholly a monster, as she knows damn well what she’s done and has buried her shame and self-criticism about it under a shell of ruthlessness – yet reveals her feelings in a moment of vulnerability which rivals those few that Cerebus displays.

All this and now in this climactic scene – shocking to the reader – she’s suddenly shown to be unquestionably the single most personally lethal character in all 6000 pages, fighting the notoriously dangerous sword-armed Cerebus to a standstill and beyond despite being middle-aged and overweight, and beginning with no weapon and a broken arm. I’d say “wow, she must have been a real bad-ass back when,” except that she believably transcends that description now.

All this and now in this climactic scene – shocking to the reader – she’s suddenly shown to be unquestionably the single most personally lethal character in all 6000 pages, fighting the notoriously dangerous sword-armed Cerebus to a standstill and beyond despite being middle-aged and overweight, and beginning with no weapon and a broken arm. I’d say “wow, she must have been a real bad-ass back when,” except that she believably transcends that description now.

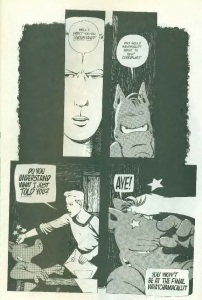

It’s probably at the top of any serious list of comics fight scenes, beginning when Cerebus suddenly realizes he’s in for it (the first page shown here), and continuing into crunching impacts, spattered gore, and gritty terror, of which the second page I’ve chosen is only a bit. Throughout, Cirin puts the Kingpin in the shade: inhumanly powerful, perfectly skilled relative to her size and build, coolly strategic, dealing with anticipated and unanticipated pain alike with the same determination, and indeed visibly, at all times, driving the fight with her indomitable will. The sequence where she sits on the steps and raises one hand, waiting for Cerebus’ attack with her death-glare on full, is chilling, and at least to me, even kind of switched me over to her side. It’s Cerebus’ only moment of pure fear that he’s going to lose a fight, and nothing leads the reader to think that he’s necessarily wrong – the confrontation only ends because the author literally intervenes, implying that even he couldn’t see his protagonist winning, and displaying through a number of interesting visual devices that he’s personally torn between these characters.

Similar to Michelle in high-impact for minimal depiction, Mothers & Daughters also reveals the real Cirin, who is not an aardvark, and whose name and social leadership were stolen by Serna. She first appears in Women, before the events I’ve described already, shown to be living under house arrest which appears permanent. She provides remarkable insight and thematic punch, but remains mysterious (who is this wonderful old gal, why do the Cirinists seem to revere and fear her so?) until Minds, when “Dave” shows Cerebus the secret history of Cirinism. The events of the usurpation are among the most psychologically horrifying of the series.

It’s a bit unfair to such an intriguing character, but I’ll stick with the one point of stressing that Cirinism is now shown not to be fundamentally flawed – only that it went off the rails into authoritarianism when Serna pulled her coup. Keep that in mind whenever you think this story is about the essentialism of male and female endeavors.

Verdict

C’mon, get with it: Sim writes and illustrates great female characters. Multiple characters? Check. Consequential backstories? Check. Differing viewpoints? Check. Different relationships to protagonist and to other characters? Check. Differing shapes and sizes, not correlated to ugly/dumb/comedic or beautiful/dumb/all-sex? Check. Understandable motives for actions, across the whole spectrum of ethics? Check. Changing viewpoints, understandable character development based on events? Double-extra-check. High-impact actions toward protagonist, and/or actions providing contrast/comparison with his? Triple-multiple-check.

Significantly, these major characters completely do not correspond to any of Sim’s invective about female irrationality and self-centered emotion. They just don’t. I submit that for the few minor characters who do, their depictions don’t pass out of the realm of real behavior which a real person or two has exhibited from time to time, and incidentally that some of these characters are male. That invective may as well have been delivered by some other guy half a world away, for all the effect it has on the story.

This post has considered only the mirroring between Church & State vs. Mothers & Daughters. My sequel post takes a larger view regarding the whole series, including the multiple roles of Jaka and the most difficult figure of Joanne.

Plea for mercy: I wish I knew how to scan at a setting which does justice to the art. It keeps coming out splotchy and uneven. In the comic, Cerebus is at no time polka-dotted.

Links: Cellulord: Aardvarks over the UK, including an interview and an array of current Sim or Cerebus links; and Open thread: is Cerebus the worst comic ever? in which, crucially, Berlatsky’s argument converts in the middle away from his title question of whether the comic is bad, to the undefined, conveniently-shifting criterion of its “legitimacy.”

Next comics: Ophite, Gnosis, p. 9 (January 21)

Next column: Gone ape indeed (January 22)

Posted on January 15, 2017, in The 90s me, The great ultravillains and tagged Astoria, Cerebus, Church & State, Cirin, Comics Journal, Dave Sim, feminism, Frank Miller, Gary Groth, Gerhard, Howard Chaykin, Jaka, Michelle, Mothers & Daughters, rape, Red Sophia. Bookmark the permalink. 11 Comments.

Hey Ron,

Thank you for writing this. Just, thank you.

Looking forward to reading part 2.

Cheers,

Tor

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m interested to know the specifics of your thanks, whether for this post or after the second part.

LikeLike

I’m certainly a non-Cerebus-er, happy to acknowledge that I’m not REALLY following when you talk about the plot. But as the ecclesiastical power games and endless twists you describe are part of why I’m not sure I’d enjoy the comic, they also might keep me from trying as hard as I could.

I did get pointed (yes, with pious indignation) at some of Dave Sims’ rants some 15-ish years back – doubtless why I’ve followed these posts attentively as a non-Cerebus-er. And while I may not have been QUITE as universally offended as the pointer had hoped, I was pretty offended. The impression I was left with (disclaimer: years ago, primed to be critical, no close analysis) was “here’s a man (Sim) who, when all is said and done, doesn’t seem to think women are really, you know, human beings. Ick.”

Given that, it’s all too easy to be suspicious about the female characters such a person creates. But I find your argument to the contrary in this particular case to be compelling – in Cerebus, many of Sim’s female characters seem fully, interestingly, engagingly human. An excellent reminder that overall, analysis motivated by such suspicions is (yes, I’m gonna say it) problematic. So that’s the specific to my “thanks, Ron.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

In preparing the follow-up post, I hit upon a useful way to phrase it, so here’s a preview. If Sim had provided essay and editorial material just as fervent, voluminous, and detailed, with the opposite message, then it would obviously be necessary to see if the story corresponded to it.

E.g., “women are great! they rock! for thus-and-such reasons!” OK, I’d say, big talk, but let’s see if your story actually does that or if you’re papering over some other content with your reassurances. And if the story does something else, then what is it.

So that’s what I’m doing here. Even if one interprets his essay/editorial stuff as its worst version (which I think the latter stages became) as “women are awful! they suck! for thus-and-such reasons!” the response is the same. OK, big talk, let’s see if your story actually does that. If it does something else, then what is it.

The key being that neither agreeement with that material nor judgment of the author’s character is at stake. Obviously both will exist for every single reader; I know where I stand on both. But my positions on them are of no conceivable interest to another human being, except in terms of inclusion/exclusion, which I don’t like playing into.

Instead, my issue is whether the comic itself matches the rhetoric, or perhaps most clearly, my issue is the comic, period. What’s it like, regarding women characters, and full stop.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is there anybody who ostentatiously excludes Dave Sim and “Cerebus the Aardvark” from modern comics discussion? The characterization in the first paragraph certainly comports with how Dave wishes it to be known, but not with history.

LikeLike

Hi! I’ll reply in two parts. First, you open with a question using “any,” which is answerable with even a single example. Noah Berlatsky’s piece, linked above, is an excellent one, and either here or in a related post (see the Dave Sim tag for a list), I’ve linked to Andrew Rilestone’s similar piece. These are not two random mopes but significant internet opinion-makers, whose positions get repeated through multiple venues.

Second, you invoke “history” as contradicting the opening statements of my post. If that’s true, you should have no trouble providing references and preferably links to correct my thinking. I welcome that – I would be first in line for a big cheer if those statements are historically incorrect.

So far, in reading a number of “about comics” and “the graphic novel” texts published in the past decade, I’ve found very little about Dave Sim, Gerhard, or Cerebus, in arguments or overviews that seem to me to call for them to be referenced. I’ve mentioned a couple of exceptions, e.g. Gerhard’s piece about backgrounds in one of the Wizards collections.Again, whatever references you can provide to correct this impression would be appreciated.

LikeLike

Hello Ron:

I have trouble parsing your first paragraph. You seem to be saying that “significant Internet opinion-makers” writing not infrequently about “Cerebus” is an example of ostentatiously excluding Dave and “Cerebus” from discussion. Obviously that proves the exact opposite, so perhaps you wrote in haste and mis-stated your argument?

As for your second paragraph: No, no — you are the one making claims of Groth-led conspiracies, so the burden of proof is on you, not on me to prove there wasn’t a conspiracy. Certainly your description is the one Dave would have us believe; it’s just that the evidence for this is quite lacking. The “I’m just asking questions,” tone of the last two sentences of the second paragraph of your article attempt to import scholarly detachment, but rather are unindicated editorial endorsements (i.e. propaganda) for Dave’s point of view. (And one correction: Dave was never made persona non grata; by his own admission, he recused himself, declining job offers, interviews, convention appearances, and eventually all appearances. Despite another of his attempts to rewrite history, Dave was never barred from comics; he left. His perfect right, of course.)

Fortunately we have Gary’s own words to go by, and the words of other contributors to “The Comics Journal”, as well as many words by Dave. Their point and counterpoint from the 1980s through the 1990s are an excellent summary of some issues confronting the comics field at that time.

Dave and “Cerebus” always punched above their weight. He was interviewed all over the place (and good for him for promoting his work so avidly; as he said, “Produce, Publish, Distribute, and Promote, or nothing will happen for you,”), including multiple times in “The Comics Journal”. His work was reviewed regularly as it progressed , in every comics-related publication (“ElfQuest” didn’t get that). He palled around with the top creators in the field at the height of their powers and influence. His opinion was both solicited and volunteered (his setting fire to Richard Pini in the publishers’-roundtable “TCJ” column was both overdue and hilarious). And of course we can’t ignore his role as de facto leader of the self-publishing movement of the ’90s.

In argument with Gary (which enmity Dave characterized as “friendly”), we find Gary and Dave agreeing on issues of ethics in comics (eg. ownership, royalties, the limitations of superhero comics).

We find Gary disagreeing with Dave’s later claim that self-publishing is inherently superior to house-publishing, and that cartoonists are morally superior to publishers (kind of a non sequitur at the time). Perhaps Dave is correct that Gary’s self-interest influences his opinion; although Fantagraphics tried to treat creators more fairly than the big publishers, I side with Dave that publishing should be the cart and creating the horse. Dave seems to have acquired some flexibility in these viewpoints today (eg. his work published by IDW, his admission that he was mistaken in the latter claim).

We find Gary, who always objected to misogyny (eg. see his statements about selecting the Eros creators and titles, or that “Blood and Thunder” contributor who insulted his girlfriend) decried Dave’s misogyny in “Reads” and thereafter.

We find Gary, I think correctly, bifurcating Dave into the guy who said comics retailers had a responsibility to order more good comics and fewer bad comics and the guy who said the ’90s speculators market was a good thing for the field.

Anyone who looks at all the on-the-record exchanges (let alone anyone who had access to a much-smaller industry’s gossip, which was freely traded as coin amoung fandom) and sees a Groth-led conspiracy to destroy Dave has more than a touch of paranoia about them.

Ah, but I know what you object to: it’s that Dave-as-Hitler cartoon in “TCJ”, isn’t it? Gary still thinks that’s hilarious, apparently, but Kim Thompson didn’t. Leaving aside that Dave actually did later create a concentration camp for women in “Fruitcake Park”, and leaving aside how much it obviously hurt Dave’s little fee-fees, an over-the-top and questionably tasteful joke hardly proves conspiracy.

As to the final paragraph of your comment: I think we agree that “Cerebus” contains much work worth studying. If you think “Cerebus” is under-represented in articles about “the graphic novel”, I suggest that at least part of the cause is comicdom’s notoriously short and selective memory. I would like to know the titles of the books you think are omitting this information, that I may read them for myself.

But “Cerebus” still punches above its weight: still in print and available, still discussed on the Internet that now is the comics press. How many of the hundreds of independent — or even mainstream — titles from a decade ago receive this much ongoing attention? Indeed, we seem to be experiencing a bit of a “Cerebus” resurgence, with the remastered editions being published and the revenue-generating title “Cerebus In Hell” in stores (and both actively supported by Diamond Distributors), the covers book, the ongoing success of the “Cerebus Archive” portfolios, articles appearing on popular comics websites, and dedicated websites like “AMoC”.

LikeLike

Uh huh. Pull the other one.

You don’t have any trouble parsing my first point. You just don’t like it. [For others reading along, if any, the issue at hand is whether “are you now or have you ever been” remains the context for discussing Dave Sim and his work. The question raised was if anyone did it. I provided two examples.]

I was tentatively hoping you’d provide information that overturned my opening summary and provided me with a more accurate and more positive outlook on the issue. After all, the point you object to isn’t the thesis of my post and we might have gotten past it and talked about what I did say. Instead, now it’s clear you showed up looking for a fight concerning a bug up your ass.

Why such mean words? Because you’re really shotgunning, choke wide-open. You’ve used “conspiracy” to characterize my position. I said no such thing nor implied it. You’ve also hammered the idea that what I’m saying is representative of Sim’s own position, as if that were a criticism, and as if I cared about conforming or not to that position, whatever it is at any point.

Downhill from there, too. Stuff your “after you Alphonse” nonsense. It’s not your blog I bombed onto with Someone Is Wrong on the Internet flag flying, citing “history,” one word, to support your position. That’s simply unacceptable, in any intellectual terms. It’s not hostile or unreasonable to ask you to back it up or to explain what sort of reference you even mean.

Then you claim to read my mind about what I’m “really” upset about, again, something I never mentioned or implied. Putting aside the notion that I’m upset in the first place, that’s junior league anti-intellectualism. Not even the snotnose grad student level you managed throughout the rest of the post. Rest assured that if I were … what, upset, anything, about that image, I’d have included it and talked about it.

It’s so unnecessary. I was open to an alternate view, which your summary of the Comics Journal discussion might have opened if it weren’t mired in your internet attack snark. I hope anyone reading this does look those texts over and comes to their own conclusion, perhaps different from my own; I’m not invested otherwise.

This blog isn’t anyone’s sandbox or kittybox. If you reply here or comment on another post, talk the fuck smart and nice, not passive-aggressive “nice” either. Otherwise your post can go in the Gone folder to join the last guy’s who didn’t heed me, the Reagan-lover who tried to ‘splain what a rebel he was.

LikeLike

And sure enough, therrrrre he goes …

Word must have got around to the Cerebus internet circles about my posts; there’s been a spate of comments on them. Until now they were a bit feisty – no surprise – but ultimately pretty nice.

LikeLike

Indeed. A link to a couple of your blogposts was recently posted to the “Cerebus” Facebook group.

LikeLike

Pingback: More women part 2 | Comics Madness