Your mama’s apocalypse

This is a partner post to Your mama’s Oh Wow as heirs to my general-introduction post about my science fiction adolescence, A dangerous vision, focusing this time on the then almost-new topic of blasted, destroyed, ruined Earth, specifically as caused by our here-and-now war and weapons policies. There’s plenty of post-nuke stuff starting as early as the late 40s, and certainly one can go back to War of the Worlds in 1898, but I’m talking about a distinctive, short-lived subset, perhaps a decade.

Hold on! I can hear you squeal! I’m not talking about solely the trappings of blasted cities and radioactive deserts, but also of a certain deadly-focused essential content: neither the bewilderment of WWII-era “wait, we won, why are we in danger now?” nor the 1980s freedom-fantasy of a cool wasteland to be a bad-ass in, but from right in between them – the rage at human destruction and stupidity. It’s a limited but full-on component of Cosmic Zap, opposed to the Cold War by definition.

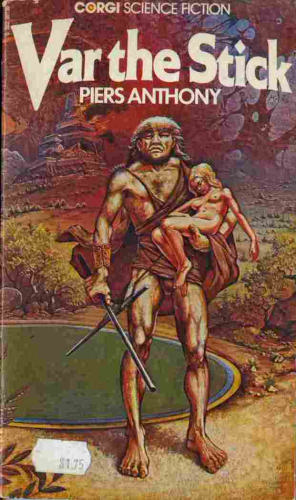

You may point to By the Waters of Babylon, Alas, Babylon, On the Beach, and A Canticle for Liebowitz, but I maintain these don’t count, or rather, they serve as the jumping-off point for what I’m talking about with a very big helping of that is not enough. (OK, maybe On the Beach counts, geez, that book.) Nor, by contrast, does Robert Heinlein’s Farnham’s Freehold (1964), which is a glittery-eyed celebration of how fuckin’ awesome the post-collapse will be once a man can be a man again. This stuff I’m talking about is, well, from just a quick dip into the bookshelves, Edgar Pangborn’s Davy and Still I Persist in Wondering, Richard Chilson’s As the Curtain Falls, Fritz Leiber’s “The Night of the Long Knives” (an early example), somesome of Philip Dick’s work, much of John Wyndham’s work, much of Harlan Ellison’s work, Robert Merle’s Malevil, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (written perhaps earlier than you think), and Piers Anthony’s Battle Circle, or rather, as originally published in three short novels, Sos the Rope, Var the Stick, and Neq the Sword. I think anyone my age who was reading science fiction at the time can name a dozen more with little effort.

You may point to By the Waters of Babylon, Alas, Babylon, On the Beach, and A Canticle for Liebowitz, but I maintain these don’t count, or rather, they serve as the jumping-off point for what I’m talking about with a very big helping of that is not enough. (OK, maybe On the Beach counts, geez, that book.) Nor, by contrast, does Robert Heinlein’s Farnham’s Freehold (1964), which is a glittery-eyed celebration of how fuckin’ awesome the post-collapse will be once a man can be a man again. This stuff I’m talking about is, well, from just a quick dip into the bookshelves, Edgar Pangborn’s Davy and Still I Persist in Wondering, Richard Chilson’s As the Curtain Falls, Fritz Leiber’s “The Night of the Long Knives” (an early example), somesome of Philip Dick’s work, much of John Wyndham’s work, much of Harlan Ellison’s work, Robert Merle’s Malevil, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (written perhaps earlier than you think), and Piers Anthony’s Battle Circle, or rather, as originally published in three short novels, Sos the Rope, Var the Stick, and Neq the Sword. I think anyone my age who was reading science fiction at the time can name a dozen more with little effort.

Do I sense a recoil from some of the titles? Many are not nice, and I maintain the disgustingness is part of the point. Unlike the older stories, they are not melancholy; they are savage and aggrieved. Babies are deformed. People are ignorant and desperate. Rape is both horrible and normal. Even Pangborn’s heartfelt, even gentle storytelling is about nothing but tragedy, atrocity, ignorance, and pain, and that’s as nice as it gets. The end of “A Boy and His Dog” is not black comedy; it’s foul and repellent, and I urge you to read it unironically. Yes, I said “read,” not watch.

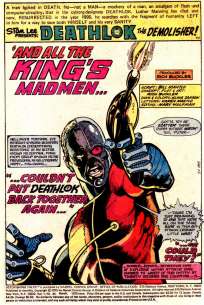

The comics smack in the middle of my first ventures to the spinner racks were on top of it, including Kamandi and the surreal war-anthology stuff from DC that I didn’t buy, and at Marvel, many of them were initiated and obviously nurtured by Roy Thomas, among them the Planet of the Apes magazine, Killraven in Amazing Adventures, and Deathlok in Astonishing Tales. If you’re reading Deathlok and thinking “rad cyborg,” then you’re not getting it. His textual inspiration, Steve Austin of Cyborg, despite an admirable darkness in his origin story, stays in the comfortable genre of standard action-espionage to fight against the Free World’s enemies – there’s no such thing here in Rich Buckler’s version (writing with various others, especially Doug Moench). And there isn’t going to be. There’s no secret chip in his brain preserving all human knowledge for the future. There’s no haven of free-thinking survivors to find and/or save. The world is gone. All the more tragic for his genuinely awesome and often hilarious sarcasm-and-awareness, Deathlok is merely its final blip and last gasp, with no hope of a New Hope, ever. You do not fantasize about being there with him. The series does wander toward the end, under Marv Wolfman’s editorship and Bill Mantlo’s writing, but if you aren’t familiar with it, you’ll be surprised at how many things you do know came from there.

The comics smack in the middle of my first ventures to the spinner racks were on top of it, including Kamandi and the surreal war-anthology stuff from DC that I didn’t buy, and at Marvel, many of them were initiated and obviously nurtured by Roy Thomas, among them the Planet of the Apes magazine, Killraven in Amazing Adventures, and Deathlok in Astonishing Tales. If you’re reading Deathlok and thinking “rad cyborg,” then you’re not getting it. His textual inspiration, Steve Austin of Cyborg, despite an admirable darkness in his origin story, stays in the comfortable genre of standard action-espionage to fight against the Free World’s enemies – there’s no such thing here in Rich Buckler’s version (writing with various others, especially Doug Moench). And there isn’t going to be. There’s no secret chip in his brain preserving all human knowledge for the future. There’s no haven of free-thinking survivors to find and/or save. The world is gone. All the more tragic for his genuinely awesome and often hilarious sarcasm-and-awareness, Deathlok is merely its final blip and last gasp, with no hope of a New Hope, ever. You do not fantasize about being there with him. The series does wander toward the end, under Marv Wolfman’s editorship and Bill Mantlo’s writing, but if you aren’t familiar with it, you’ll be surprised at how many things you do know came from there.

These comics went for the bull-goose loony version even harder than the prose: not merely the loss of a given civil order or government of the moment, but that the very possibility of such things is lost – culture and history are probably or certainly permanently shattered. Don’t look for any “rising from the ruins” or the sort-of reassuring notion that history is cyclical, so we’re the ancients and there’ll be more moderns eventually. The wastelands aren’t limited in scope; the whole ecology is destroyed. Living things’ genetics are damaged permanently; far from being cool or newly-adapted, the mutants are wretched and malformed. Anyone still walking around is an afterthought.

This is how TV and movies of the same era kept messing it up, with only a few exceptions. Many are marred by their throwaway production value and the accompanying throwaway attitude toward the content, e.g. Damnation Alley (another story people oughtta read rather than hooting about the film). More significant, however, is the subversion of the point, which although typically only partial, was very common.

- Reversals of the pessimism at the 4/5 mark or the very end, with a new Eden or a thriving enclave of survivors

- Interestingly, in its “after the end” stories, the original Star Trek tended more toward utter tragedy than glimmers of hope

- Sequels with considerably less intelligence and challenge

- Planet of the Apes is unusual in including four good films and a bad one, rather than one good and four bad

- Complete breakdown of story integrity into maundering, preaching, flat-out dropping the premise, bad visual haiku, or action tropes, for which the standout is the appallingly bad Logan’s Run

- A cunning version: more and more comedy or irony or whatever you call it that suggests it’s all a joke really, e.g. Deathrace 2000

- A subtle version: the full-on plot shift to traditional western-film storylines

I think this hesitancy and inconsistency of the visual media came to dominate the fan memory of the period and the concept. After that, over the following decade, it’s pretty easy to see the Farnham Freehold version take prominence; I nod with nausea at the Survivalist series. Consider how Mad Max (1979, an entirely Australian production) shows the destruction of morality entirely along with the collapse of modern life, whereas Mad Max 2 (1981, called The Road Warrior in the U.S., backed by Warner Bros) shows lone-heroic morality and community hope shining even brighter now that human experience is stripped down to a romantic frontier. Clarification: I think The Road Warrior is a very good action/western film, but it thematically completely reverses and replaces Mad Max, rather than being any kind of sequel. If it were a sequel, that early scene would include him eating, not dog food, but the guy who tries to bushwhack him.

Comics as I experienced them were far less ambiguous. My purchases at the time included most of Amazing Adventures 18-39, the “War of the Worlds,” or the Killraven series, created by Thomas and several others (e.g. Neal Adams, Howard Chaykin), but mainly associated with Don McGregor and a range of artists including P. Craig Russell. In it, 11-year-old me got to read about human family-farms where the aliens eat the babies.

It’s War of the Worlds, right? Wrong. In Wells’ novel, the aliens are done-in by microbes, i.e., they were doomed from the start. Grim as the initial shock of being overcome in military terms may be for humanity, it’s nothing but mere shock – actually a necessary philosophical wake-up call. Whereas this isn’t “war,” it’s flat and total annihilation and subjugation of what’s left. The Earth is ruined and even reality is distorted to a hallucinatory level. The Martians fucking win.

It’s War of the Worlds, right? Wrong. In Wells’ novel, the aliens are done-in by microbes, i.e., they were doomed from the start. Grim as the initial shock of being overcome in military terms may be for humanity, it’s nothing but mere shock – actually a necessary philosophical wake-up call. Whereas this isn’t “war,” it’s flat and total annihilation and subjugation of what’s left. The Earth is ruined and even reality is distorted to a hallucinatory level. The Martians fucking win.

It’s no wonder plenty of retro-readings include the complaint that Killraven and his crew never pull it together and take the bad aliens down. People want John Christopher’s The Pool of Fire, they don’t want fuck-you, breed another baby for dinner, or revelations that transform emotions but offer no key to victory, or bizarre encounters which go nowhere and leaving the hero wondering why he bothered to kill the thing instead of merely dying in its grasp. It’s not an epic, it’s a series of tone poems. The heroes are often admirable, but sometimes conflicted and confused, and always one step removed from what you or I would do, as they are not our representatives or role-models. They’re doomed – not as immediately as the main characters in “I Have No Mouth But I Must Scream,” but you can see it from here.

It’s very, very little to do with mid-twentieth century science fiction and fantasy, at that time neatly defined into categories by magazine editorship and soon by book distributors. Its’ much more to do with pulp sword-and-sorcery, sometimes called science fantasy, sometimes called science-and-sorcery – but removing the distance of epochal time (past or future) and moving the occasional, lurking nihilism and suicidal existential horror in Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith to front-and-center. Prose examples were common too, almost all completely lost to fandom, e.g., Keith Jarrett’s little-known but brilliant Witherwing.

Killraven nailed this confluence to the wall, greatly because it so relied on visual beauty to drive home the horror. The prose too: I stand by my comments in Still beautiful even more so here, that although it’s practically obligatory for comics pundits to sneer at McGregor’s style, the very same people gush and swoon at the same techniques used by other authors.

Killraven nailed this confluence to the wall, greatly because it so relied on visual beauty to drive home the horror. The prose too: I stand by my comments in Still beautiful even more so here, that although it’s practically obligatory for comics pundits to sneer at McGregor’s style, the very same people gush and swoon at the same techniques used by other authors.

I repeat, “apocalypse” as a 1980s-and-later action genre is a pale and unintelligent shadow of what I’m talking about. Here, the physical excess and release found in the violence is not wish-fulfillment at all, but of a piece with the horror – because killing a foe solves very little, either emotionally or socially. There is no hope for a restored society; the doomed little enclaves and messed-up cults are all we’ve got and they aren’t going to last. The Battle Circle trilogy is a very good example too, as it nods toward manly sword-fighting in a cool wasteland, and towards the rise of a new society – then shows just how horribly twisted and impossible those things become.

I grant you this utter-pessimism After the End concept did not wholly die and I’m sure you’re bursting with what-about-what-about for later authors. However, I urge you to set aside those stories which include cyclicity, irrelevance (“Old Earth, long gone,” but so what), and always, wish-fulfillment (“nuclear war, what a bummer … but now we get to fight with swords/shoot zombies? cool!”), to see what a minority we’re talking about, which for only a brief period was the genre itself.

An odd time for one’s formative years in pop culture, wasn’t it? All of it was in infrastructural transition, decidedly not smooth: comics in between newsstand and retail, as well as in editorial hopscotch at both DC and Marvel; science fiction in between editor-driven magazines and distributor-driven retail, in the brief context of maverick editors and rebel fandom; cinema in between the meltdown of the Hollywood studios and their consolidation into mega-corporations. For a moment the actual culture struck and spattered into the visible and available media without filtering. No wonder I was looking at a bitter and suicidal Spider-Man (Spider-Schlep), a crazy-idealistic, equally suicidal hippie Jesus (Superstar), and intellectually-precise freaking-out (Cosmic muck, EEEEEEAARRRHHAHH!); at science fiction defined by rage and hedonism (see this post’s opening links), as well as fantasy defined by pure excess, including the forgotten cultural origins of fantasy role-playing (Naked went the gamer, Goddess of rape); and the well-known explosion of great-awful-what-the-fuck at the movies.

Having been so formed, and given what has come after, Killraven makes far more sense to me now than I’d ever imagined.

Links: Longbox Graveyard, Rip Jagger’s Dojo,

Next column: Scary war (March 12)

Posted on March 5, 2017, in The 70s me and tagged A Boy and His Dog, Amazing Adventures, Deathlok, Don McGregor, Doug Moench, Edgar Pangborn, Harlan Ellison, Keith Jarrett, Killraven, Mad Max 1979 film, P. Craig Russell, Rich Buckler, Roy Thomas, The Road Warrior 1981 film, War of the Worlds, Witherwing. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

Leiber’s “Big Time” is a good example of the cosmic catastrophe, or end of history/death of the universe apocalyptic fantasy. This fantasy lacks the concrete & intimate detail of “town you know & monuments you’ve seen reduced to ash and bone.” But it has a kind of cosmic horror. And with Leiber the big trio of sex, violence, and power are still there.

I never read them during my adolescent sci-fi reading, although I knew their plots from “Encyclopedia of …” and secondary lit. A few years back I got to HEAR them courtesy of Librivox:

https://librivox.org/the-big-time-by-fritz-leiber/

https://librivox.org/the-night-of-the-long-knives-by-fritz-leiber/

LikeLike

I referenced “Long Knives” in the post – one of my teen readings, arguably formative regarding not idealizing sex. Leiber had a strong influence on me, which you can probably see all over Sorcerer and Trollbabe even without the pulled quotes. I can’t really see _The Big Time_ as part of what I’m talking about, but then again, it’s not like hard-and-fast defined boundaries exist, and so if it works for you, that’s fine. I do see the politics fitting right in: total contempt for the concept of “sides” in the Cold War..

LikeLike

Your OP got me thinking about degrees of apocalypse in fantastic literature and imagery.

Sci-fi sometimes pulls back from the local- to the planetary-, and beyond that into the cosmic-scale apocalypse. “Big Time” features a fantastical war for domination of the universe’s entire timestream, and a few veterans of that conflict try to find a way to get out of the endless war between the archons who hold our world in their clutches.

Our little lives and the great catastrophic terrors of the Little Time — like the victory for the Axis in Leiber’s story — are just skirmishes in a greater war. There are “reasons” for what Earthlings experience as catastrophe, but knowing them doesn’t help us in any way. The humans conscripted to fight in the war between Snake and Spider get a perspective on horrible disasters but can’t stop them and help other humans, or the other species of the cosmos.

But both stories also contain the hope that the survivors can build some kind of human life for themselves despite terrestrial apocalypse or cosmic dissolution. Here’s Lili from “Big Time”:

______

“It was a wonderful thought, but now we cannot carry

or send any message and I believe it is too late in any event for a

peace message to do any good. The cosmos is too raveled by change, too

far gone. It will dissolve, fade, ‘leave not a rack behind.’ We’re the

survivors. The torch of existence has been put in our hands.

______

I like how Leiber at both the level of the pair scrabbling for survival in “Long Knives,” and at the cosmic level in “Big Time,” doesn’t loose a grasp of either palpably base and human motivations or human-scale visions of alternatives.

LikeLike

Plus Leiber will always get me with his allusions to Jacobean playwrights like Webster and Shake.

LikeLike

I couldn’t find an essay-worthy reason to include details about Deathlok like grappling a handlebar-mustached naked man to death in a psychic limbo space. But in case you didn’t know, that happens.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I know death hath ten thousand several doors

For men to take their exits.”

LikeLike

Was there a feed from underground sci-fi visions to the mass market visual culture? I only know about Slow Death Eco Funnies 2nd hand from articles in Epic & other publications. But those really ugly visuals of decayed bodies and savaged landscapes pack a punch. They are more than just backgrounds for a bad ass-hero to adventure through.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am generally convinced that underground work is continually mined by anyone and everyone else engaged in mainstream publishing, for all media, and that this mining is usually covert or tacit rather than licensed and promoted as such. Even the most superficial glance at comics and cinema shows this to be the case, and the more I look – e.g. my recent engagement with music of the 1970s – the more I see. I don’t know if an identifiable feed exists; I suspect it’s more a matter of “this is how it’s done,” acquired simply through being in that culture.

I don’t know if any general or academic work exists which investigates this process as a matter of infrastructure. If there were, and if it’s readable and coherent (by no means the default expectation), I’d dive into it immediately.

I agree with you profoundly about the visuals, and I probably should have acknowledged George Metzger’s Moondog in full, as well as Richard Corben’s various imaginings.

LikeLike

Both “A Boy and His Dog” and later Battle Circle kind of messed me up, because they both start in that “cool post-apoc badassery” space and end in serious WTFland. I remember not getting the end of ABaHD until the third or fourth reading, and finally going “Ooooooh… OH!” And Battle Circle made me feel kind of betrayed, as the awesome barbarian badasses I’d been encouraged to root for just suffered ruinous defeat after ruinous defeat.

I think I prefer the other versions, tbh. *goes back to playing Horizon Zero Dawn, in which you shoot explosive arrows at mechanical t-rexes from the back of your robo-horse in the ruins of 3010 Colorado*

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, hellyes. Maybe it’s more about my particular reader-experience than the stories themselves, but what passes for bleak/grimdark/whatever storytelling today seems more about, um, gory special-effects (written or otherwise) than true despair. My touchstone would be the story “Her Smoke Rose Up Forever”, by Alice Sheldon-as-James Tiptree, Jr. Eventually, we learn Earth is dead. Dead, dead, dead. Like our protagonist. Not that that in any way means our protagonist is done suffering … nor that any of us are.

For what it’s worth – what you’ve said/shown about Killraven makes me very sad to have missed it back then.

That said … the first time I read Brin’s “The Postman”, I was thrilled to find authentic hope alongside the despair. But the rest of the 80’s cured me of that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Scary war | Comics Madness

Pingback: Your mama’s apocalypse