Scary war

Posted by Ron Edwards

I completely missed war comics as a kid, and the reason is easy: the covers scared the shit out of me, the few I found in the pile of comics I’d inherited, e.g. Sgt. Rock, no less than those I’d see on the stands when I started buying comics, like Weird War Tales and War is Hell. It was both ideological and visual. I was born very literally into the American social crisis of “why are we in Vietnam,” and my personal take from as young as six or seven was that I would not participate in war even at the most superficial level. As I saw it, if the comic glorified war, then I didn’t want to touch it, and if it defied or protested war, then I didn’t need to be told. I was also a sensitive little wussy-boy and recoiled from all naturalistic imagery of gore and pain.

I completely missed war comics as a kid, and the reason is easy: the covers scared the shit out of me, the few I found in the pile of comics I’d inherited, e.g. Sgt. Rock, no less than those I’d see on the stands when I started buying comics, like Weird War Tales and War is Hell. It was both ideological and visual. I was born very literally into the American social crisis of “why are we in Vietnam,” and my personal take from as young as six or seven was that I would not participate in war even at the most superficial level. As I saw it, if the comic glorified war, then I didn’t want to touch it, and if it defied or protested war, then I didn’t need to be told. I was also a sensitive little wussy-boy and recoiled from all naturalistic imagery of gore and pain.

Then, when I became re-interested in comics history back in the 1980s, I missed the war comics again by not investigating, because I was ignorant of their significance. Therefore this is, in many ways, the anti-blogger post – no expertise, no personal experience, no promised insight or opinion for you to repeat. I’m writing about my present-day realization that not to know war comics is not to know comics. They’ve never ended. Forget superheroes, war is the baseline for American comics, what they always have delivered.

I won’t summarize the comics during WWII, only mention that all the companies well-known to comics fans published them, and to nod toward Timely/Atlas’ bucket of titles and the characters The Human Torch, Captain America, and Namor the Sub-Mariner, for whom creators like Bill Everett and Jack Kirby need little mention to current readers, as well as toward writers like Mickey Spillane. I’m mainly talking those with relatively naturalistic content that continued as war comics.

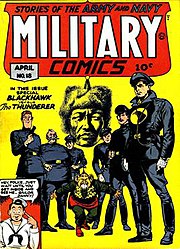

For example, Blackhawk, probably the comics progenitor of the multi-national “ace” team which is rooted in Doc Savage and would become codified for most current readers in the 1980s G.I. Joe. It began at Quality Comics as a contemporary WWII concept in 1941, appearing first in Military Comics and Uncle Sam Quarterly, becoming a title series in 1944, featuring Will Eisner and Reed Crandall, its primary artist. It was acquired by DC in 1951, ran from that point until 1956, and has intermittently appeared through the present day: e.g. folding them into superhero continuity in a new title in 1967, canceled in 1968; it was resumed in 1976 as part of the DC Explosion, casting the team as contemporary mercenaries, canceled in 1977; revived by Len Wein in 1982, set in WWII again, and canceled in 1984. Most of the titles and characters I’m writing about have similarly on-and-off, multiple-revival, this-war-no-that-war histories, but I stress they were not confined to the WWII origin + 1950s-only presence, far from it.

I don’t know how the 1950s versions related to the thousands of manly-mag covers and stories, which were still very present through the mid-70s and were such obvious posturing that I had to laugh even as a kid, as well as the only-slightly more sober gung-ho military tales you found in Reader’s Digest or any number of other everyman-styled venues. I do know that to whatever extent newsstand comics corresponded to that kind of material, a bunch of them or a bunch of content within them did not. There’s a comics-principle for you, I guess: by the time you can see that comics confirm something identifiable as cultural content and values, it’s a sure bet that some other comic is already defying it. And in 1951-1954, where else but at EC, and who else but the inimitable Harvey Kurtzman, with Two-Fisted Tales, 1950-1955, and Frontline Combat, 1951-1954.

I don’t know how the 1950s versions related to the thousands of manly-mag covers and stories, which were still very present through the mid-70s and were such obvious posturing that I had to laugh even as a kid, as well as the only-slightly more sober gung-ho military tales you found in Reader’s Digest or any number of other everyman-styled venues. I do know that to whatever extent newsstand comics corresponded to that kind of material, a bunch of them or a bunch of content within them did not. There’s a comics-principle for you, I guess: by the time you can see that comics confirm something identifiable as cultural content and values, it’s a sure bet that some other comic is already defying it. And in 1951-1954, where else but at EC, and who else but the inimitable Harvey Kurtzman, with Two-Fisted Tales, 1950-1955, and Frontline Combat, 1951-1954.

It may seem as if there’s pro-war over here and anti-war over there, easily recognized as such, on-message as such, wholly internally consistent. The Hooded Utilitarian critiques Blazing Combat from that perspective, but mine is different: rather than seek a comic which meets a gold standard of utterly anti-war, I look for bits and pieces across stories, often incoherent or mismatched to surrounding material, which throw doubt or generally subvert the ostensible or “obvious” message. The key is whether such things show up regularly rather than merely being isolated rarities.

That’s the perspective I’d bring to educating myself about the other major titles begun in the 1950s and some of which, unlike the EC titles (killed by the Comics Code Authority), thrived and continued into the late 70s or early 80s:

That’s the perspective I’d bring to educating myself about the other major titles begun in the 1950s and some of which, unlike the EC titles (killed by the Comics Code Authority), thrived and continued into the late 70s or early 80s:

- War Comics (Timely/Newsstand Publications): begun in 1950, probably the first revival of the genre after the war’s end and tightly keyed to propaganda regarding the Korean War (1950-1953), swiftly followed by many similar titles; its advent and the military content are paralleled by macho-adventure titles like Man Comics and Spy Fighters, as well as the long-running Stag magazine.

- Other titles by Timely/Atlas included Battle (1951-1960), Battlefield (1952), and Combat Kelly (1951), notable for its violence and featuring Al Hartley, two phrases I had not previously encountered in the same sentence. See the link at the bottom for tons more, especially documenting the shift in content after the Comics Code Authority struck in 1955.

- Some names you’ll recognize across the comics include Stan Lee, Al Hartley, John Buscema, Syd Shores, Jack Kirby, Joe Sinnott, Don Heck, John Severin, Russ Heath, Joe Orlando, Bob Brown, Dick Ayers, Dave Berg, John Romita, Gene Colan, Jerry Robinson, and George Tuska.

- Star Spangled War Stories (DC): begun in 1952 initially retitling Star Spangled Comics, running through 1977; editor Robert Kanigher

- G.I. Combat: first published by Quality Comics, 1952-1956, acquired by DC to run 1957-1987; Robert Kanigher and Joe Kashdan are the primary writers

- Our Army at War (DC): 1952-1977, by Robert Kanigher and Joe Kubert. Sgt. Rock is introduced in 1959, initially as a WWII veteran serving at NCO.

- Our Fighting Forces: DC, 1954-1978, although I don’t know how continuous it was. Robert Kanigher was the editor and primary writer.

- Fightin’ Army / Air Force / Navy / Marines (Charlton): four titles begun approximately in 1954 allowing for title changes and another publisher, running through 1977 with hiatus and reprints through 1984.

- All-American Men of War (DC): 1956-1966 (this one’s confusing, it seems to have run for longer but I don’t know when)

I went into this detail, minimal by comics scholars’ standards, for three reasons: (1) how prevalent the titles are, zooming and booming straight through what comics fans and scholars think of as the dramatic destruction of American comics in the late 1950s (yes, volume did decrease; the thing is how the number of war titles didn’t, and although the content altered, it didn’t vanish); (2) the specificity of the creators, showing how dominated the genre was by Kanigher, Kubert, and a few others, and on a related note, how many of the future greats made their bones and developed their creative relationships on these titles; and (3) the strong tendency to focus on WWII rather than Korea and (later) Vietnam, which sometimes included criticizing current war policy in a safer fictional space.

On to the titles I know a little bit more about that began in the 1960s, which as you can see from the dates above should be understood as added to and included in most of the above titles and concepts, rather than replacing them. No surprise really that dissent is more explicit, with the most obvious example in an effective revival of the EC titles from a decade-plus earlier, Blazing Combat magazine from Warren Publishing (see … To see something really scary?). It appeared in only four issues during 1965-1966, featuring 29 stories set in a wide variety of war settings, including “Landscape” in #2, from the North Vietnamese POV. It was unabashedly violent horror and explicitly anti-war. Archie Goodwin wrote it all, Harvey Kurtzman was an active consultant, and it featured the usual Warren all-star artists.

On to the titles I know a little bit more about that began in the 1960s, which as you can see from the dates above should be understood as added to and included in most of the above titles and concepts, rather than replacing them. No surprise really that dissent is more explicit, with the most obvious example in an effective revival of the EC titles from a decade-plus earlier, Blazing Combat magazine from Warren Publishing (see … To see something really scary?). It appeared in only four issues during 1965-1966, featuring 29 stories set in a wide variety of war settings, including “Landscape” in #2, from the North Vietnamese POV. It was unabashedly violent horror and explicitly anti-war. Archie Goodwin wrote it all, Harvey Kurtzman was an active consultant, and it featured the usual Warren all-star artists.

There’s also a visible shift in the newsstand comics, which I saw some of in the pile of comics I inherited from my siblings. Given my brief exposure, the content seems consonant with my points in G.I. Who. Some of it might be tied to the editor change-up at DC starting in 1968, with Carmine Infantino bringing Kubert and Kanigher up to editor status, as well as Goodwin and Dick Ayers on frequent writing duty, and Jack Kirby too, so it’s no surprise the content became more reflective and if not anti-war, questioning in a non-ambiguous way, including the the Enemy Ace (early, 1965), the Haunted Tank, the Losers, and some Vietnam stories in Our Army at War; in 1970 it would start featuring Sam Glanzman’s autobiographical stories. The same title introduced the Unknown Soldier in 1966, who’d go on to become the main character in Star Spangled War Stories in 1970, to replace the series title name in 1977, and to last until 1982. Our Army at War changed its title to Sgt. Rock in 1977 and ran until 1988.

The same thing happened at Marvel, throughout the 1963-1981 run of Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos, beginning with the multi-ethnic noncom squad during WWII by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, then evolving through Roy Thomas and Mike Friedrich (the main writer). As with DC, you can see the 1950s war-pros rising to the occasion: e.g., Ayers who did 95 issues of Sgt. Fury often inked by John Severin. Friedrich and Ayers also did two edgy Marvel WWII series: Captain Savage and his Leatherneck Raiders (1968-1970) and Combat Kelly and the Deadly Dozen (1972-1973).

Now for what really scared and repelled me when I first went to the spinner racks with my two quarters and assortment of smaller change. First, Weird War Tales from DC, 1971-1983, edited by – no surprise allowed – Joe Orlando, his EC and scary-war-shit from the 1950s on full display. Get this: the series is hosted by Death, full of explicit horror and occult elements, including post-apocalyptic stories like “The Day After Doomsday.” Its terrifying twin was Marvel’s War is Hell, 1973-1975, which began with reprints of old war comics, then shifted into nightmare territory, in which Death is the main character, forcing a doomed soldier to die countless lives in war theaters across history. Really, these two are just one big shared title, considering the shared pool of writers between them and their venue for creators’ break-ins, similar to Warren Publishing. WWT featured the first comics work by Walt Simonson and the first collaboration between Roger McKenzie and Frank Miller; WIH featured early Chris Claremont and Steve Gerber.

Now for what really scared and repelled me when I first went to the spinner racks with my two quarters and assortment of smaller change. First, Weird War Tales from DC, 1971-1983, edited by – no surprise allowed – Joe Orlando, his EC and scary-war-shit from the 1950s on full display. Get this: the series is hosted by Death, full of explicit horror and occult elements, including post-apocalyptic stories like “The Day After Doomsday.” Its terrifying twin was Marvel’s War is Hell, 1973-1975, which began with reprints of old war comics, then shifted into nightmare territory, in which Death is the main character, forcing a doomed soldier to die countless lives in war theaters across history. Really, these two are just one big shared title, considering the shared pool of writers between them and their venue for creators’ break-ins, similar to Warren Publishing. WWT featured the first comics work by Walt Simonson and the first collaboration between Roger McKenzie and Frank Miller; WIH featured early Chris Claremont and Steve Gerber.

I am baffled that I should have been an avid reader of such novels as The Forever War by Joe Haldeman and stories like “Run for the Stars” by Harlan Ellison, but such a wuss about these. They’re totally of a piece with my seminal influences described in A dangerous vision and Your mama’s apocalypse. As a minor point, I’m interested to know how Weird War Tales crossed the hard line (1975) between Infantino’s editorship and the Jenette Kahn era, and why War is Hell faltered during a period of massive uncritical buildup of Marvel titles.

Anyone reading this blog knows already that I am running, not walking, to read each of these from start to finish, and that I don’t consider anything about my 70s comics writing complete until I do so. I have tons of Joe Kubert material under my belt as a reader and also in collections; like anyone who knows what a comic is, I know that Kubert was one of the giants of modern comics as both creator and mentor. But I am awed by even my first look at his war content, how much of this whole thing was shaped by his life and passion concerning the subject – a passion which was by no means mindless patriotic militarism. Add Kanigher, Goodwin, and Orlando immediately.

Anyone reading this blog knows already that I am running, not walking, to read each of these from start to finish, and that I don’t consider anything about my 70s comics writing complete until I do so. I have tons of Joe Kubert material under my belt as a reader and also in collections; like anyone who knows what a comic is, I know that Kubert was one of the giants of modern comics as both creator and mentor. But I am awed by even my first look at his war content, how much of this whole thing was shaped by his life and passion concerning the subject – a passion which was by no means mindless patriotic militarism. Add Kanigher, Goodwin, and Orlando immediately.

After this? You got me there, my experience stops almost cold. I know literally nothing about the latter years of Sgt. Rock and Sgt. Fury or about Men of War (DC’s title change for All-American Men of War, 1977-1980); and as I’ve written about before, I was oblivious to the 1980s version of G.I. Joe. I’ve never seen a physical issue of The ‘Nam (Marvel, 1986-1993). But … am I wrong in thinking that the “war comic” that lasted this long (1950-1980 or so) is mostly gone today? Or that in whatever versions replaced them, that the particular veteran-experience and generally-reflective undertone of so many war comics has vanished? I have quite a bit to say about the alleged end of the Cold War and the illusion that “we’re all peaceful now except, oh no, terrorists” that was promulgated in the 1990s, but about the comics, I’ve only seen a couple examples and need some help framing these questions and addressing them.

I know even less about non-U.S. comics set in actual combat. The easy comparison is that the U.S. population hasn’t experienced a war on its own territory since the 1800s so “we don’t know” and romanticize and idealize more than others do, but I’m not too sure that’s true. It wouldn’t surprise me if the uneasy mix of glory-and-doubt were present in such comics worldwide. I’d also be interested to know whether in-theater war content in comics (as opposed to aftermath-setting) came under legal restrictions, especially in postwar Germany, Italy, or Japan.

A premature generalization? (1) That from 1945-1985 or so, when being in the American military was a matter of conscription and brief one-war enlistment except at the highest ranks, and as U.S. culture grappled with the perceived virtue and perceived mandate of winning wars while insisting we did no such thing, war comics permitted perspective and dissent as part of, rather than specifically opposing, the dramatic and sort-of heroic depiction of historical combat. Don’t be simplistic: before you say “Americans were critical of war in Vietnam and the comics just rode on that,” bear in mind that Nixon won his 1972 presidential campaign in a shocking landslide, on a wave of fervent patriotic “we will win” rhetoric and putting down dissenters as whiners and wimps. (2) That from roughly 1985 and certainly from 1991 to the present, as narratives of war shifted especially for Vietnam, as the image of “the Russians” changed from nigh-insuperable, frightening alien forces into those stupid wimps we beat (and were beating all along), as the Israeli model became idealized and tightly tied to U.S. policy, as the military moved into its first generation of career-model for the non-officer ranks, combat-theater war comics fell right out of the mainstream. No spate of hard and gritty Against the Terrorists and Our Fightin’ Peacekeepers appeared – and this in knowledge of how thoroughly the Pentagon supports and promotes its policies and desired public image via cinema.

But why? Could it be that comics are the opposite of cinema, that although (selon Truffaut) you can’t make an anti-war film set in a war theater because war’s too much fun to watch, you can’t make a genuine pro-war comic set similarly because … of something? (with the proviso that “a” is too simplistic, it’d have to be assessed across a spectrum of titles and stories)

Whether that’s right or wrong or aiming wrong in the first place, I dunno. Time to learn about it.

Links: A history of Timely-Atlas war comics (1950-1960), Joe Kubert dies at 85 (NYT obituary), A tribute to Robert Kanigher (Comics Alliance), Weird War Tales covers (you’re welcome), War is Hell covers (ditto)

Next column: It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s an implosion! (March 19)

Posted on March 12, 2017, in Politics dammit, The 70s me and tagged Archie Goodwin, Blazing Combat, Carmine Infantino, Comics Code Authority, Dick Ayers, Entertainment Comics (EC), Frontline Combat, Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Kirby, Joe Kubert, Joe Orlando, Robert Kanigher, Sam Glanzman, Two-Fisted Tales, War is Hell, Weird War Tales. Bookmark the permalink. 30 Comments.

Well, since you asked me on G+ to comment here, here goes. I’d be interested in your take on The ‘Nam in that I know from your other writings that you have personal experience that leads you to specific conclusions about that conflict. Which, I have found interesting in the past.

The comic takes as its conceit that each issue covers on month of the war. Not that each issue is a full month but, they move through the conflict at that speed. So, for the first 12 issues is the main characters full 1 year tour of duty. And, the first year has Michael Golden on art for which he is well suited. The comic seems to have been inspired by Michael Golden and Doug Murray Vietnam stories they published in the short lived Savage Tales (and were clearly the best stuff to come out of that revival. Well, that and the John Severin stuff that was in there). For the most part it focuses on the soldiers lives rather than the politics but, politics does rear its head in it’s portrayal of war protesters and how returning soldiers were treated after returning and similar stuff (as you might imagine). And, also in some of the statements about whether it was winnable or not. Though, it is unclear whether these are the perspectives of the writers or the characters. It does try to portray various aspects of the war like the experiences of locals who previously allied with the French and now with the Americans. One of the strengths of Michael Golden’s art for the series is that his semi-realist approach (by which I mean the characters are somewhat cartoony but, equipment is not) and presentation of the landscape of Vietnam really gives it a sense of being a real place in which these things happened in a way that a lot of discussion of it does not. That in itself really makes it worth at least a casual look.

After Golden and Murray left the series went downhill relatively fast and fell into hackneyed late ’80s tropes and generally, less inspired writing and art. Still, I felt the first couple years good enough to save and while, I think it does have a somewhat flawed presentation of the history, I do think this flawed perspective was common to many of the people who went through it (at least from talking to a variety of people who went through it).

LikeLike

Thanks for posting! The summary does intrigue me and I suppose I should sit down with a collection.

I’ve writtten about the curious shift in the cultural identity of the Vietnam veteran: (1) anti-establishment, even counter-cultural, definitely associated with draft resistance; to (2) troubled-patriot, brotherhood-in-arms, spat-upon. How this comic plays into that is unquestionably a big deal, especially since it seems to be the “serious” counterpart to the G.I. Joe series as far as Marvel-reading teens of the late 1980s would be concerned.

I like the month-by-month structure, it’s a device for immediacy which I’d expect to be used more often, historically.

I don’t suppose any perspectives of those Vietnamese opposed to the U.S. presence were presented?

LikeLike

I need to reread my collection of British war comics now. I don’t recall them having much that could be read as anti-war politics – they were all pretty much “against the Nazis!” – which tends to squeeze out anti-war sentiment even in people who are otherwise anti-war. (But I’m personally sympathetic to the Indian and Burmese nationalists, who fought against the British during WW2. It’s a long and cool story.)

Biographically, my reading of war comics followed, and superseded, my early reading of superheroes. By the time I was about 13, both had been replaced by pulp SF and fantasy. I didn’t get back into comics until the mid-80s, under the impact of superhero RPGs like Champions.

The idea that “you can’t make an anti-war film set in a war theater because war’s too much fun to watch” seems counter-intuitive to me. I’m not into film theory, but the anecdotal exceptions seem to point against it. Kubrick’s “Paths of Glory” is the first that comes to mind, and there are others. But of course I don’t necessarily understand what Truffaut was suggesting.

The reverse case is interesting – the creation of pro-war comics. To state the obvious, I would be perfectly happy if such comics were impossible to do well, but I don’t think that is the case. I’m talking about “hard and gritty Against the Terrorists and Our Fightin’ Peacekeepers” here.

The thing that makes me think that is that there *are* comics that cover “anti-terrorist”-type storylines. They are just dressed in superhero clothes. The Punisher is an example.

I don’t think the fact that he is an individual, rather than a team, is relevant.

What could be relevant is the mistrust of government in (US) popular culture. In some ways, a rogue individual is more acceptable than a team of government agents. I think this could be successfully worked around.

LikeLike

Hi Alan,

I’d like to learn more about the British comics – titles, years, the basic information. I imagine they’re similarly anthology-oriented; is that true?

That’s a good point about the Punisher, and it ties back to my and Steve Long’s writings about the character in early 2016. Specifically, that his initial opponents (when he wasn’t being hornswoggled or distracted into trying to shoot Spider-Man) were mobsters who’d managed to skirt the attention of law enforcement, even establishment types or tied to them in some corrupt way. He didn’t focus on “punks” or drug traffickers straight out of Hollywood casting until later. However – he *did* relatively quickly shift to terrorists, e.g. the one-initial-changed “PLF,” when written by Len Wein.

The U.S. confusion about rogue/patriotic violent actors is very hard to explain outside of the culture, and without knowledge of the John Birch Society. Suffice to say that government (what’s now called “Deep State”) aims are often upheld as virtuous, but that only men who break silly government rules immediately constraining them can achieve those aims. So you’re anti-authoritarian, see, but you are helping the powers which … keep us safe, or something … get what they want. So the rogue is the super-patriot after all. (I didn’t say it was rational …)

I tend to think that Truffaut’s right enough for discussable points or meaningful debate , at least regarding depicting violent combat as plot, or at least that avoiding the problem he describes takes a lot of care. It also matters that I don’t regard many mainstream films to be genuinely anti-war, so much as “gee we’re so troubled, but hey, let’s kill some evidently unmotivated malevolent bad people,” e.g. Platoon.

Movies like Paths of Glory, Das Boot, Gallipoli, Born on the Fourth of July, and Full Metal Jacket support the point in that they depict very little combat relative to their running length and plots, that the primary conflicts are about something else, and that the violence tends not to be hand-to-hand, victory-through-effort, but the kind which kills at random. I’ve observed, too, that fans of Full Metal Jacket actually don’t know the movie very well and can’t recount the plot, instead incessantly repeating one or two scenes they think are funny.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. Thank you. I was about to manifest my foreigner confusion. It’s like reading Miller’s DK1 and thinking it’s left wing and rebellious, then reading his more recent comics and going “oh, well, so THAT’S where he was going with that”. It’s something that I guess you could see surprisingly clearly in Lucas’ prequel trilogy, that this young guy who’s got a problem with authority grows up to be a fascist dictator. It’s where I see a lot of Internet “D&D alignment” jokes/debates get confusing, like, are ‘loveable rogues’ like Han Solo really Chaotic Good? Aren’t those the same guys that get Lawful Evil once they GET power? I guess you guys are always circling back to the cowboy, the guy who’s outside the law but who’s there to impose his own law.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. I am the editor on a new book which collects every single USS Stevens story that Sam Glanzman ever wrote and drew (not counting the two A Sailor’s Story graphic novels he did for Marvel, which I collected separately). It took two years to put together. I hope you’ll check it out! Here is the Amazon link: U.S.S. Stevens: The Collected Stories (Dover Graphic Novels) https://www.amazon.com/dp/0486801586/ref=cm_sw_r_cp_api_vxIXyb8CYFPGG

Best,

Drew Ford

P.S. You’ll also see links on that page to the A Sailor’s Story and ATTU collections that I put together for Sam. And Sam’s Red Range collection which will be out in June of this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Drew! I’m honored and greatly appreciate the comment.

When and if you’re inclined, I hope you’d be willing to review my posts concerning war and the comics in/about them. It’s starting to look as if I have a book in the making, and that would certainly be a chapter.

LikeLike

You wish you knew more about non-U.S. comics set in actual combat, you say? Boy, do I have a big piece of history to share with you… 😉

https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRtbUK98ooD4dEg6q1t_PwpMtdGex55K0W0mvt3JPC4bTM1PdaMHw

https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcQAsaleVfS9RJXRurEZWG3C0bOpvGlx3M_d7SGVMtEhw4CXa9t01A

LikeLike

Santiago, can you describe or characterize the comic for me? How does it relate to the points I made in the article, if at all?

To my knowledge, the only military events in Argentina during my lifetime were during the Falklands Crisis (i.e., Las Malvinas) in the early 1980s, which I followed carefully at the time and often had to explain to the older people around me, who were typically astonished at the islands’ location. Let me know if I’m missing other important events.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, no, that’s part of what’s interesting about it! They’re mostly anti-war comics made in the 1950s set in the World War II. A lot of them, like *most* of them, are framed stories in which the narrator is the character Ernie Pike, based on an actual historical figure called Ernie Pyle. All of them are scripted by Héctor Oesterheld, a comic book scriptwriter that’s like our patron saint of comics; think of Stan Lee or Osamu Tezuka.

Now, if you want to see him write a (sort of) war story that happens in Argentina, fast forward a few years later to 1957’s El Eternauta (recently translated and released in the U.S., and the last of the links I put, it’s a shame that it alone didn’t show up as an image), which is a science fiction/survival/apocalyptic/invasion story.

Here in the outskirts of the empire, it’s never obvious to us that we can set the things that we make in our own cultural background. Oesterheld and Borges were lauded for making genre stories set in Buenos Aires; before them, Argentines would write SF or crime fiction and set them in USA. The rock bands of the 60s are considered pioneers for daring to sing in Spanish, previous rock bands sang in the best English they could, as if the language was part of the genre.

That being said, not being at the center has its own perks. I don’t want to make this too long so I’ll just say that you get to read and get influenced by everyone else (sometimes the French and the Americans, for instance, don’t read each other) and that I’m certain that Oesterheld’s war stories are top notch, some of the best done ever, no matter the country.

(I wonder if in the US you ever get that kind of alienation. Maybe manga lovers? Do you have, like, artists that draw in the style of manga but don’t read each other because they’re not “really Japanese”?)

I’ll think about the points made on the article and about other Argentine war comics of other decades, even the ones set in the Falklands, and I’ll comment again if I think of something pertinent.

(Oh, and thanks for the “Malvinas”, I guess I should be patriotic and call them Malvinas too, it’s just that I call them Malvinas in Spanish and Falklands in English, like a Deutschland/Germany/Alemania thing.)

LikeLike

I’ll look forward to more information about all of them!

I hesitate to summarize the stereotypical treatment of Argentina relative to war, here in the U.S. It’s really insulting: that the country harbored a zillion fleeing Nazis and was probably ruled by Hitler, or Hitler’s brain in a jar, afterwards. And no, this isn’t just pop culture. It would be surprising here to see that Argentinan comics didn’t present a pro-Nazi view of the war.

This ties into your other point about artists. Obviously a few Argentinan comics creators became famous here, e.g. José Muñoz, but as with almost any country, that almost never translates into a general appreciation of the comics culture that Muñoz or whoever came from. For instance, people in U.S. comics culture only talk about Filipino artists insofar as they get published by American companies, despite the constant influx of creators and the considerable influence they’ve had. [Japan is the exception, in the reverse direction, tending to favor the brand rather than the specific works, styles, or all but a very few creators.]

Therefore my impression is that other nations’ war comics are almost entirely opaque to the U.S. audience, even to the sort-of critical audience like me – you have to be an active scholar to get the basic knowledge. We don’t know the larger comics context in those cultures enough to understand the range in which “a comic” could be made, and we don’t have any good historical grasp of how a given nation relates to WWII, either at the time or since. (U.S. history education is notoriously light on the Soviet history, very similar to British in this regard.) (I’m often able to astonish people by asking them to describe what Lebanese, Syrian, or Palestinian nationalists did vs. what Zionist nationalists did during the war, meaning, they don’t know, and what they speculate is dramatically different from what happened.)

LikeLike

Also: Ernie Pyle is a household name here in the States, or was when I was young. His death during the final months of the war is considered a national tragedy.

Given his focus on the common-man perspective on war, I’m absolutely fascinated by the idea of a non-U.S. comic centered on him. I would love to read these.

LikeLike

(It appears we’ve reached the WordPress limit on nesting; I’m replying to myself with fear that my response will appear higher than your text which I’m responding to. Let’s cross our fingers and see.)

I have to admit that the idea that we’ve been secretly run that Hitler irks me when I think that A) We have the biggest Jewish community in the world outside of Israel and NY; and B) We gave birth to Che Guevara.

What we do have is Perón ingrained into the DNA of our culture. Reading your blog I often ask myself if he could qualify as a Doom figure, the way you said about Tito. As a left-leaning person myself, I dislike that he was a General and the center of a cult of personality, but he’s center-right at worst, nothing to do with the far-right dictators we got later, aligned with the CIA and funded by the US until the Carter administration, with the hopes that we didn’t become a Communist republic aligned with the USSR. That was what was great about Perón: he was democratically elected twice in a row (and a third time 15 years later), he wasn’t aligned with the CIA nor USSR nor anyone, his simpaties lay more with Mussolini than Hitler (and they were both gone anyway… right? Maybe not?). The Argentine Left resents him for raising the salaries of all workers, giving them vacations, medical care and etc rights, because maybe-just-maybe if all workers had been kept exploited as they were, they would’ve rebelled and made a socialist utopia. Who knows.

I shouldn’t make this post longer by going into detail about the super-interesting, mega-tragic history of the Argentine Left in the 60s and 70s, where they decided they should use guerrilla tactics against the dictatorship (common sense), but they also decided to present themselves under Peronist banners (because if you’re a Marxist you should follow the lead, love and whishes of the working classes, right?). They finally achieved their objective of getting Perón back from exile, only to see him very quickly turn on them and denounce them, sort-of-on-point, as infiltrators in his movement. Which meant death for a lot of them. (The lesson of history is: If you’re a Leftist guerrilla fighter visiting your leader-in-exile and he receives you in Spain under the protection of Franco, beware.)

But I wanted to make a mention of this because it ties into the comics thing: All four daughters of Oesterheld, and later Oesterheld himself, were dissapeared in the dictatorship that came after Peron’s death. (That was the one junta where Kissinger infamously told them “Do what you have to do, but do it quick”.) So in the 50s he was doing anti-war comics and probably didn’t like Perón very much and his view of the working classes was at best patronizing, but in the late 70s he was in hiding, writing the scripts to the graphic novels of the biographies of Evita and Che Guevara.

Phew! That took a lot more than I anticipated. I guess I’m healthily emotionally moved by the history of my own country. In another time I’ll look for more on Ernie Pike, see if I can link something here for you to read.

One more thing about that phenomenon where people dissociate artists from surrounding culture: This is also the country where Corto Maltese’s Hugo Pratt learned to make comics. He worked side by side with Oesterheld, and he was actually the artist of “Ernie Pike”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a nice surprise, there’s a very helpful and accurate English Wikipedia article on the comic: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernie_Pike

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here we go! It’s not much, but it’s two links, three stories. All in Spanish, sorry about that. One isn’t drawn by Pratt, and is captioned in English by an (I think) Brazilian blogger. The other two are colored and re-edited; the poster shows an original page for comparison.

http://thecribsheet-isabelinho.blogspot.com.ar/2014/12/ernie-pike.html

http://www.lasegundaguerra.com/viewtopic.php?f=272&t=12261

LikeLiked by 1 person

1. My God, Perón! I didn’t think of him (and her) in reference to my topic in the post because I don’t associate them with bang-bang-explosion war situations, but in retrospect, that’s the obvious throughline to investigate.

2. My life-history take on the matter shows my limits: I associate Perón with people like Ferdinand Marcos and Reza Pahlavi – which may be unfair? Not sure; these associations are all tied up with the Reagan era, the Falklands/Malvinas, and the curious elevation of sentimental, uniformed pomp in U.S. culture. “Evita,” especially Madonna’s version of “Don’t cry for me, Argentina,” is the probable single touchpoint for any U.S. citizen’s notion of the nation.

3. Given your summary, one might contrast Perón as a soft-right centrist who gets pilloried as a fascist, with Allende, a soft-left centrist who gets pilloried as a communist.

In the interest of maintaining the nesting, and considering the specialization of the topic, let’s take further discussion to email.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damn, I commented all smug like thinking the links would translate to pages and now the comment it’s awaiting moderation and I don’t know what’ll happen. So I’ll confess the trick: Just google for “Hora Cero Revista”, and you’ll see where all those images came from.

https://www.google.com.ar/search?q=hora+cero&espv=2&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjultyR4NLSAhVBC5AKHa5vBocQ_AUIBygC&biw=1440&bih=745#tbm=isch&q=hora+cero+revista&*

LikeLike

(…meant to say “thinking they would translate to images”)

LikeLike

They do translate to images, but I’ve set the comments to permit a maximum of three links.

LikeLike

The British stuff I was reading came from a number of publishers, but they all used the same style.

The Wikipedia entry for one of these publishers is here. Looking at a couple of the issues in my collection, it seems accurate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commando_(comics)

There was typically one story per issue, apart from “Holiday Specials” and the like.

Stories were one-offs, with no continuing characters.

Creators were rarely credited, apart from the odd artist’s signature. Some of the artists were from outside the UK, including at least one Argentinian.

There are rarely complete copyright notices, so publication dates are tricky. The material I was reading appears to have been the real British publications, not Australian reprints. (Many of the early DC comics I read were reprints.) I wouldn’t put it past them to reprint old stories, but failing that, the material I was reading was roughly from 1973-1975, give or take a year.

There were, apparently, Australian war comics back in the 40s and 50s, but the industry had essentially died off before I came along, except for reprints.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A tangent to follow might be comics or special editions of comics aimed at soldiers.

http://www.moaa.org/Content/Publications-and-Media/MOAA-Blog/Friday-Fun–Marvel-s-Latest-Military-Only-Free-Comic-Book.aspx

Eisner used comics to spice up preventative maintenance magazines for the Army

You can get his Preventative Magazines online: http://dig.library.vcu.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/psm

I read somewhere that he did V.D. pamphlets too.

LikeLike

One analysis of G.I. Joe comics suggests that they don’t address the politics of war directly. According to Norlund (http://bit.ly/2mLB2Hl): “GI Joe comics differ significantly from other superhero comics because of these perpetual themes of nationalism and patriotism. By contrast, for example, the X-Men comic books use themes revolving around coming of age, isolation through being different, and the responsibilities of power.” There are pokes at trends in American society but no take on current wars or anti-terrorist operations.

LikeLike

I’m confused. I read his piece to mean that the non-Joe comics were not about nationalism and patriotism, and that the Joe comics were.

LikeLike

Sure. Nationalism and patriotism as something that Joe team members promote and embody as characters. Not in any coarse “Smash the X” or “Our heroic boys on front Y” propagandistic way.

LikeLike

The war comics around here have a national-identity building function in addition to promoting patriotism and the war effort. Look, Canada, we play hockey, we protect the North, etc.

And generalized machismo promotion:

Nelvana, with a female heroine and some recognition of the country’s ethnic composition, was kind of a pleasant surprise when she was rediscovered a few years back:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are or were they subsidized or otherwise facilitated through government effort? I’m given to understand that during the 1970s, at least, Canadian musicians received considerable support and direct promotion or exposure through one or another federal department.

LikeLike

Without Wiki-ing.

Paper rationing and duties on foreign reading matter allowed a comics boom around WW II.

Active cultural promotion is part of nationalistic surge in the 60’s and 70’s. Members of London/Paris-looking educated elite culture tries to get cultured institutions going in the major centres, & lots of Brits come here to get work in them (like our classical theatre troupes or national broadcaster).

The CBC and National Film Board have a strain of cultural uplift in them that shies away from grittier popular culture, aside from sports and family-friendly folk music. It takes writers like Mordecai Richler and Michel Tremblay to talk about wrestling, go-go dancing, boxing, and transvestites. The National Film Board had some very experimental animators who really contributed to the visual cultural and my personal memories.

The music industry benefited from Canadian content rules on radio. That’s been cut back in recent decades and now you apply to very particular grants or subventions or programmes. Rock rumour: Trudeau really liked Crowbar of “What a Feeling” fame and wanted to make sure Canadian rockers got a break:

I don’t think Gene Day or Dave Sim or Chester Brown really benefited from any direct support. There are minor subventions for publishers but graphic novels were not the kind of thing that got a lot of Canada Council grants.

Drawn and Quarterly could get going in Montreal because, well, Montreal is cool. And way cheaper to live in than Toronto.

You get a weird reflexive effect of 70’s trouble makers messing with Canadiana with genuine affection and a nationalist intent, but who simultaneously poke fun at old-timey or officially-recognized national mythology.

http://www.comicbookdaily.com/collecting-community/whites-tsunami-weca-splashes/casting-call/

I was really lucky to have Ken Gass as my 1st year acting teacher at the U of T. And if you look at the program, you might recognize a name from Dances with Wolves and Entourage –Maury Chaykin.

— Rock Digression Follows —

I loved reading this book in my Middle School library and it remains a classic. If you want exposure to the full spectrum of 70s goodness, check out Axes, Chops and Hot Licks, a mid-70s tome on our local music scene.

http://ritchieyorke.com/axes-chops-hot-licks/

This country is huge. And if you make it from coast to coast and the border to the permafrost, you have certain bragging rights. Dave Bidini lived it and wrote about it.

http://www.cbc.ca/books/2014/10/on-a-cold-road-tales-of-adventure-in-canadian-rock.html

Bidini is great on sports, music, media, and eloquent about how important these everyday experiences are. (And he’s a mensch).

“Have Not Been The Same” documents indie rock & shows the way in which marginal and weird acts benefit from a little institutional support but have to find their way on their own. A little bit of cash to make a video. 1 CBC DJ who will play your stuff late at night. A few college radio stations. And the rest, well, you are on your own. Out of that, some of my best memories were made.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating, all of it. I have always squinted at the odd contrast between the U.S. perception of Canadians as peaceniks (probably stemming from the draft resistance issue during the Vietnam War) and the Canadian romance with the military, which is evident from casual observation.

My example of the perhaps over-enthusiastic promotion of Canadian pop artistry is Gordon Lightfoot. My wife said, “Who?” and then discovered she could sing along to every song on the Sundown album.

I don’t know all the details, but my understanding is that Chester Brown produced Paying for It on some kind of federal grant. I want to stress that I’m not implying anything specific by saying so, nor by my original inquiry about it – only a contrast with American comics, whose economic expectation is generally predicated on the bootstraps and cream model. (In the U.S., the only comparable entity is the Xeric Foundation, which is of course private/non-profit.)

LikeLike

The situation is very different from when I was a kid. There are municipal, provincial, and federal sources of income for one-offs or for enterprise support. Look, a public health insurance scheme is a godsend for creatives. IIRC Robin Laws once remarked that it was what allowed him to be a full-time game guy.

NOWADAYS Brown is recognized as a very significant artistic voice. Uh, hand. Same with Seth. The Toronto Reference Library has a very lively graphic novel and comics boutique, and runs very fine programs related to it.

Sook-Yin Lee, a character in Brown’s book, is emblematic of the change in Canadian identity. She pokes around the corners of Canadian identity with wide-eyed wonder. For years she hosted a C.B.C. show called Definitely Not the Opera, a poke at the national broadcaster’s replaying of Metropolitan Opera episodes for decades on Saturdays. No fawning on elite high culture or folksy stuffiness of the C.B.C. for her.

http://www.cbc.ca/radio/dnto

And she always had a great combination of sincerity and goofiness:

xhttp://www.cbc.ca/radio/dnto/what-does-it-mean-to-be-a-hero-1.3502900/dntosuperhero-trading-cards-collect-them-all-1.3503089

Canada’s national identity is tied up with the military very closely. The casualties at Vimy Ridge in WW I are looked at as the blood sacrifice that got us our stature as a “real” nation (in French Canada the conscription thing is looked at much differently). D-Day is our way of “mucking in” with Mother England and showing those Yanks that Johnny Canuck is as hardy as they are.

If you want the cross between two big circles on the nationalist Venn diagram — hockey & military nostalgia — then there is song “50 Mission Cap” by the Tragically Hip.

A hockey card tucked under a beat up WW II Air Force hat it is both the subject of the lyrics and the source of their content. The mysterious disappearance of a player’s body is tied to a decline in the fortunes of English Canada’s team the Leafs. Until the corpse is recovered, they don’t win a cup. It would be cut-rate Joseph Campbell-style archetype games if it weren’t actually the simple sequence of events memorialized by the card.

There is a rancor towards the U.S. that comes out in a song like American Woman, a resentment of the tougher, richer, more successful guy on the block. “What’s so great about him, huh? He’s a total jerk. I’m way more sensitive, and real, and honest, than that guy” — followed up by classic beta misogyny for the American Woman who goes out with that phony creep, American Man. (Lester Bangs pointed out the resentful psychology of that song decades ago).

LikeLike

Woah, it’s an AMERICAN military cap — the semiotics of this song are way more complicated than I imagined:

LikeLike