Stones, smoke, and light

A lot of my writing in this blog is retrospective, keeping most of the content removed from my present-day circumstance and present-day events in comics. But this one’s pretty close to home and I’ll share. The series Berlin nears its completion with the publication of issue #20, presaging the conclusion of the trilogy thus far seen in City of Stones and City of Smoke with City of Light.

A lot of my writing in this blog is retrospective, keeping most of the content removed from my present-day circumstance and present-day events in comics. But this one’s pretty close to home and I’ll share. The series Berlin nears its completion with the publication of issue #20, presaging the conclusion of the trilogy thus far seen in City of Stones and City of Smoke with City of Light.

As with so many comics-related things in the 1990s, I was first introduced to Jason Lutes’ work in the back pages of Cerebus, specifically his Jar of Fools, which I bought the instant I saw the collected paperback. Anyone who read Inking is sexy will instantly recognize that Jason’s work is right in my zone. Granted, I like almost any comics art with a ton of the stuff in it, but his combo of even lines, strong outlining, and solid blacks is special, managing to be both detailed and clear. He’s right in there with Hergé, and in my mind, there’s a cluster which also includes Rick Geary and Alison Bechdel.

What he brings to it even more so, though, is ambition. Berlin began in 1996, aiming at a detailed political account of the city from 1928 through 1933, shooting for the highest possible visual and cultural detail. And like I said, first published by Black Eye Productions and now by Drawn & Quarterly, it’s getting close to the conclusion planned in #22.

What he brings to it even more so, though, is ambition. Berlin began in 1996, aiming at a detailed political account of the city from 1928 through 1933, shooting for the highest possible visual and cultural detail. And like I said, first published by Black Eye Productions and now by Drawn & Quarterly, it’s getting close to the conclusion planned in #22.

Isn’t that kind of … slow? Hey – you ask me, a person can do a comic when and how they want. This one, as well as Eric Shanower’s Age of Bronze, goes slow and steady, well, mostly steady, considering other work like Houdini: The Handcuff King and Jason’s prof job at the Center for Cartoon Studies.

There’s something important about the time in this case: how much has happened here-and-now from 1996 to today, which the book comments on substantively. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not a fascism! fascism! alarmist, Trump is Teh Nazis guy … no, I’m a lot worse than that. You don’t want to know how I think the term fascism, strictly defined, applies to the country I was born in. Just sing that anthem at the football game and be happy. What I’m referring to is the issue of small-d democracy, i.e., the simple fact of voting within some kind of governmental framework, and how it intersects with but does not represent either individual experiences or social organizing. Weimar’s a good example, and so are we – it’s not about specific purported parallels, or a predicted outcome, but about different examples of the same phenomenon.

Now I’ll shift back to the virtues of the comic, subtopic: style. First is its diversity of pace, ranging from a whole page dedicated to nuances of a glance, or a clarinet solo; to landscape poems and way-of-life portraiture; to complex dialogue full of shifting relationships; to explosive action.

The story also plays fun and loose with its focus, diving into the thoughts of any character whenever (in fact, justifying the existence of the thought balloon as a unique contributor), careening into surrealism to show a character’s musings and perceptions, using sound effects when it seems to work and not when not. Yet the effect is profoundly naturalistic, in part due to the meticulous – hell, monolithic – architecture, but also because the thoughts and effects are so familiar. A surreal imagined effect is how the mind really does it, so it’s naturalistic after all.

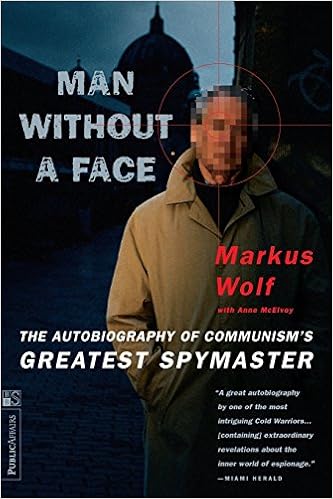

So what’s this about me and Berlin? It began with a 2004 essay which included a toss-it-in protogame as an example, using grey-spy literature for maximum moral crisis. Later, I decided I might have been onto something and thought about maybe doing a game, so dove into that literature, which I hadn’t done before, and from there into the equally grey world of Cold War spy-everything. Oddly, when I read Markus Wolf’s Man Without a Face., something snapped – and I embarked on a genuinely insane project to combine education, non-fiction writing, and role-playing, which I called Spione (German for “spies”).

So what’s this about me and Berlin? It began with a 2004 essay which included a toss-it-in protogame as an example, using grey-spy literature for maximum moral crisis. Later, I decided I might have been onto something and thought about maybe doing a game, so dove into that literature, which I hadn’t done before, and from there into the equally grey world of Cold War spy-everything. Oddly, when I read Markus Wolf’s Man Without a Face., something snapped – and I embarked on a genuinely insane project to combine education, non-fiction writing, and role-playing, which I called Spione (German for “spies”).

The overall saga of Spione is both successful and upsetting, as I think I wrote a damn good book (hell, buy it here) and the game in it broke all kinds of ground, but the more general web project fell apart – and I lost the incredible Wiki I built that cross-referenced an insane amount of spy fiction, non-fiction, and journalism. For me personally, the project was incredibly life-changing. The relevant point here is that during its production during 2005-2006, I had visited Berlin five times, embarked on learning conversational German, and developed a network of friends and chance acquaintances across the country.

Back to the comic (again) and how it relates. Wait, the fall of the Weimar Republic is a wee couple-three events earlier than Spione‘s Cold War focus, right? And it’s true, the political culture and the cityscape were so shattered in the interim that not much really translates directly. However, as with all the great divided cities, Berlin is profoundly layered by events, and if you know the history, get to know locals who care about it, and walk and look carefully, the just-previous past is extremely important for viewing your primary period of interest.

Once I began visiting there – five times in 2005-2006, as well as trips to other regions – the comic took on more power in my mind, and I combed through it with care. That’s how I knew where to stand at the bridge on the Spree where Rosa Luxemburg was killed, or why I demanded we drive slowly through the roundabout on the way to the stadium. Or for the opposite case, how I knew what had been leveled to make way for the Soviet War Memorial in front of the Brandenburg Gate.

Once I began visiting there – five times in 2005-2006, as well as trips to other regions – the comic took on more power in my mind, and I combed through it with care. That’s how I knew where to stand at the bridge on the Spree where Rosa Luxemburg was killed, or why I demanded we drive slowly through the roundabout on the way to the stadium. Or for the opposite case, how I knew what had been leveled to make way for the Soviet War Memorial in front of the Brandenburg Gate.

It’s no surprise that a fair amount of the scenes and characters’ situations concern the nightlife, as the single touchpoint for the period in American culture is Cabaret. If you don’t showcase how gaudy and desperate it was as the Nazi menace looms in the background, then according to the culture, you’re not “doing” Weimar. Trouble is, that narrative is both superficial and shopworn, and it’s not just a matter of other arts. It’s about the depth.

Ronald Taylor’s Berlin and its Culture and especially Charles W. Haxthausen and Heidren Suhr (editors), Berlin: Culture and Metropolis challenge the general notion that pre-WWII Germany, and especially Berlin, was a pathologically distorted culture. The logic of that notion runs, well, the Nazis and the war and the Holocaust were such horrible things that only a “sick” culture could have produced them, so now let’s dig about in the previous twenty years and show how sick it was. And then there’s the over-specific flipped version, which is to point to this-or-that national leader, or to problems in one’s own society, and say, see, see, there’s the sickness, rising again.

Ronald Taylor’s Berlin and its Culture and especially Charles W. Haxthausen and Heidren Suhr (editors), Berlin: Culture and Metropolis challenge the general notion that pre-WWII Germany, and especially Berlin, was a pathologically distorted culture. The logic of that notion runs, well, the Nazis and the war and the Holocaust were such horrible things that only a “sick” culture could have produced them, so now let’s dig about in the previous twenty years and show how sick it was. And then there’s the over-specific flipped version, which is to point to this-or-that national leader, or to problems in one’s own society, and say, see, see, there’s the sickness, rising again.

Whereas these books, and I submit, Jason’s Berlin as a whole, examine the period from the perspective that everything happening in it is – while historically specific – completely normally human, and worth discussing right in-and-among the raft of other social-political circumstances of our lifetimes and just before, rather than as the separated outlier. This is both less gaudy and more disturbing than the pathology-based viewpoint, which has lasted way longer than the circumstances of the propaganda that spawned it, and serves to distract from a clear conversation about what modern social life and politics are actually like.

Disclosure: The reader has probably already noticed that I use first names for the comics creators I know personally and surnames for those I don’t. Jason and I have not met or talked much, but we follow and comment at one another’s social media.

Some more good books: David Clay Large, Berlin; Brian Ladd, The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape.

Links: Jason Lutes’s Drawn & Quarterly page, CBR.com: Jason Lutes talks the final days of “Berlin”

Next column: Two villains (May 21, if the actually-happening-now move to Sweden doesn’t entirely flatten me)

Posted on May 14, 2017, in Politics dammit and tagged Berlin: City of Light, Berlin: City of Smoke, Berlin: City of Stones, Black Eye Productions, Cold War, Drawn & Quarterly, Jar of Fools, Jason Lutes, Spione RPG, Story Now. Bookmark the permalink. 108 Comments.

“You don’t want to know how I think the term fascism, strictly defined, applies to the country I was born in. ”

Um, why yes. Yes we do.

Also, out of curiosity, why have current political events been off limits for this blog.

Not that I’m complaining, this continues to be some of the finest cultural critique out there.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Damn, now I have to work up a solid reply.

I’ll start with the last thing first, the current political events part. I’m not sure what you mean: as a topic for a post, or in the comments? Also, where is there a directive about current events? Did I imply or say it in a post? I couldn’t find anything in the posted blog rules to indicate “off limits.”

(Fascism later. Might take a bit.)

LikeLike

No directive, just an observation. Honestly, I find your political and cultural stuff so relevant that in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election this was one of the first places I came, searching for some way to make sense of the whole mess, and was then surprised that the One Thing That Literally No One Else Can Shut Up About isn’t really directly discussed here. And you tend to be very deliberate about things, and this then made me start to wonder if there wasn’t a specific reason that you haven’t talked about it, and then I got curious as to what that reason might be.

That’s all.

– Tor

LikeLike

It’s a valid point. The specific reason is … well, both too general and too specific, I guess.

I think the fault or problem or failing of U.S. political culture – and if we want to artificially focus on presidential elections – occurred first in 1948 and second in 1972. Meaning, certain trends like productivity vs. wages, or the effective one-party system, or the cheap oil trick, or the re-instatement of slavery throughout the nation (instead of just Texas and Florida), or the attempted harnessing of reactionary religion both domestically and in foreign policy, were put in place during the WWII-to-Vietnam era, and, since then, ramped up to become policy itself, and not once subjected to serious criticism in policy terms or even public comprehension.

In this context, Trump is a blip, and just about all current/memetic language for correcting it/him obviously means returning to the heinous business as usual. I don’t see that as very inspiring. So focusing on him is too specific, and focusing on the big picture is too general to address “recent events” in and of themselves.

LikeLike

(this is weirdly not letting me reply to your June 20 comment, so replying here)

You said:

“It’s a valid point. The specific reason is … well, both too general and too specific, I guess.

I think the fault or problem or failing of U.S. political culture – and if we want to artificially focus on presidential elections – occurred first in 1948 and second in 1972. Meaning, certain trends like productivity vs. wages, or the effective one-party system, or the cheap oil trick, or the re-instatement of slavery throughout the nation (instead of just Texas and Florida), or the attempted harnessing of reactionary religion both domestically and in foreign policy, were put in place during the WWII-to-Vietnam era, and, since then, ramped up to become policy itself, and not once subjected to serious criticism in policy terms or even public comprehension.

In this context, Trump is a blip, and just about all current/memetic language for correcting it/him obviously means returning to the heinous business as usual. I don’t see that as very inspiring. So focusing on him is too specific, and focusing on the big picture is too general to address “recent events” in and of themselves.”

I guess I was afraid of something like that. For what it’s worth, I think that if there is an upside to Trump, it’s that it’s causing a lot of people to have a political awakening that extends far beyond Trump himself, and I’ll leave it at that.

– Tor

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let’s do this in steps. Here’s part 1; Tor, I want you to respond before I do part 2, OK?

I want to establish that it’s not controversial to use the term “fascism” as a wider phenomenon than strictly Benito Mussolini’s regime in post-WWI Italy. No big deal there, right? After all, it’s characteristically applied to the National Socialist Party rule in Germany (that’s “Nazis,” colloquially), perhaps even more so than to the party that popularized the term.

I’m good with the standard concept that both of these regimes or movements were alike enough to be lumped together and that the lumping term is, so to speak, on tap for when it might apply to any other such regime or movement. What I’m preparing to say next relies on this concept, so before I eat up more bandwith, I want to make sure this isn’t going to be a point of contention, or to resolve it if it is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I 100% have no problem with the idea that fascism as a phenomenon might apply outside of Mussolini Italy or Nazi Germany; in fact, I’ve made similar arguments myself in the recent past.

– Tor

LikeLike

Cool. On to …

Part 2: Let’s talk about what’s meant by an “ism” or any equivalent. For example …

The term “democracy” has been abused into absurdity. It only and simply means voting is somehow involved in governance. Which is very old and very widespread, throughout tons of governmental systems which differ greatly from one another in many other features. There isn’t any such thing as “a democracy,” merely this-or-that democratic feature in this-or-that historical situation, for better or worse with no apparent pattern to find.

As associated with the U.S., it’s been idolized into far more than that meaning: (i) associated with the republic-style aspects of the U.S. Constitution and the separate branches of government, (2) associated with prosperity and general satisfaction with life, (3) associated with U.S. foreign policy since WWII. However, U.S. political culture isn’t any shining example. Even taking the documentarian version at its face value – best described as “let’s organize referenda,” this has never applied to the nominally eligible U.S. population in full. And what little it’s had on actual policy, that’s been scuttled step by step throughout the Cold War period. Simultaneously, my (3) above has confounded “democracy” or “genuine democracy” with U.S. identity and policy to an absurd extent, such that if “we” do it, then it must somehow both represent a uniquely democratic outlook (whatever that is) and be the product of a uniquely pure and effective democratic process.

All this is to say that the presence of democratic steps or features in a governing system is no immunizer against or falsifier of its fascism. Nor does being fascist obviate or have to “topple” the democracy.

I presume that there’s no need to go into similar detail regarding “communism” or “socialism, both of which have been similarly bloated into “systems” rather than policies, and as well, confounded so thoroughly with one another that I’m just as happy throwing both terms out.

Here’s another nonsense term: “totalitarianism.” Even more so, in fact, as it’s strictly a policy wonk word to justify demonizing specific targets of policy – spin. It has a definition, but no state or society accords with that definition, past or present; humans don’t become automata, ever.

Those things which are usually pointed to to indicate it – excessive state security, paramilitary youth movements, characterization of a fictional persona for the state, regimentation of the workplace, identification of “productive” work with personal virtue, obscure and pettifogging bureaucracy, identification of a certain governmental office as “the leader,” gaudy reversals of formerly dissenting customs or holidays into celebrations of the state, ecstatic and even orgiastic festivals to display loyalty to the state and enthusiasm for its policies, identification of a specific religion with the virtues of the state, identification of acceptable minority religious activity by its fixed loyalty to the state – are not only common across many instances, they apply astoundingly well to the U.S., beginning just after the Civil War and taking quantum jumps after each World War.

Tor, I assume I’m being boring and obvious and failing to get to the point, but long experience has taught me to do it. Otherwise I’ll get one and a half sentences out before someone gets hysterical about totalitarianism and communism/democracy, usually ending by shouting “Stalin! Stalin!” So … just hoping for one more confirmation from you that I’m making sense, or if necessary any pointed criticism from you of what I’ve said, to lay it down before I get there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ron, If you what you are saying is “Democracy is this one thing that has existed in a lot of different forms in a lot of different societies for a long time, but in America the term has become loaded down with huge amounts of baggage that have nothing to do with the act of voting” then I’m totally on board.

I’m not sure I’m on board with your comments re: totalitarianism. Because no society has ever achieved some Platonic totalitarian ideal we can’t talk about totalitarianism? Wikipedia: “Totalitarianism is a political system in which the state recognizes no limits to its authority and strives to regulate every aspect of public and private life wherever feasible.” Surely there are people who believe in this, and surely there have been political systems that have done their utmost to achieve this, and surely some of these political systems have been more successful than others. Is it really that controversial to say “the Soviet Union under Stalin was a totalitarian state”? Or, the United States in 2017, for all its flaws, is not a totalitarian state?

In reading your indicators of totalitarianism and how they exist in the US, I’m like, ‘okay, I can see the connection’ but it still seems like there’s a comfortable gap between 9 million political dissidents murdered under Stalin and the United States treatment of its own citizenry.

I mean, am I missing something?

LikeLike

Lots to unpack, I’ll do it in a couple posts. First part, regarding democracy:

I’m going a bit further than that to say that there isn’t a noun, “democracy,” distinguishable from comparable nouns. In other words, the U.S. isn’t “a democracy” because that’s not a category.

The U.S. merely includes a plethora of democratic techniques scattered about its larger political culture/system, just like tons of other societies, past and present, each with its own particular profile. Calling the U.S.’s profile “democracy,” let alone the best or most original or purest one (“true democracy”), and tying its historical aggregation of voting techniques to a bunch of other stuff (e.g. states/federal organization, rules for parties, court system, specific laws) is walking into a swamp.

However, I don’t think going this far into that topic is important to our current one. My only goal here is to forestall the “But we can’t be fascism, we’re a democracy” reaction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Ron,

No problem with those statements whatsoever. Please proceed.

Tor

LikeLike

Re: totalitarianism – I’m struggling against the internet argumentative event horizon.

The Wikipedia definition holds its own negation through the flexibility of its terms. “Wherever feasible,” “state authority,” “regulation” …

The essential element goes unstated: that the totalitarians exert terrifying and unique techniques to turn their citizens mindless, and that (according to this view) they succeed, so, therefore although various other situations are “bad” or “tragic,” they are at least not evil in an alien and robotic way. This is hardcore Cold War talk: if I had a dime for “but at least it’s not totalitarian” regarding Chile under the Pinochet regime, Spain under the Franco regime, Zimbabwe under the Mugabe regime …

It strikes me that arguing this point is getting off track. I’ll try to get back on, but I can’t resist pointing to one thing about your response. Even by that definition, how many people abused or killed during a given regime is not stated as an indicator. Do you see how you shifted the issue by asking that? “Totalitarianism is not a category.” “But Stalin killed zillions of people!” Tons of human societies have killed zillions of people in an organized way, whether their own citizens or otherwise or both. To debate about how many, or whether that means this or means that, is to be diverted quite badly.

On track then: I’m not saying the USSR wasn’t, or that the USA is – I’m saying the term itself isn’t a meaningful category, and there is no “is” to evaluate. My concern is to remove “totalitarian” from the discussion of fascism, just as I did with “democracy,” and for a similar reason: the reflexive cry of “we can’t be fascist, we’re not totalitarian like STALIN” is very quick.

However, whether it really does/doesn’t exist as such isn’t core to my upcoming “is the U.S. fascist” reply. I’m OK with merely shelving totalitarianism as a term rather than genuinely agreeing to eliminate it, if that’s OK with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Been mulling this over. I think I get what you’re saying about the term “totalitarian,” that it’s a term that’s been used selectively to target political enemies of the US. I didn’t realize how selectively the term had been used during the Cold War. A little googling around found an article from the Hoover Institution saying that “The Chilean military regime from 1973 to 1990 was authoritarian, certainly, but not totalitarian” and ending with “It’s time to acknowledge that the legacies of the Pinochet years are a much better mix than they are usually said to be.”

Hmm.

I also didn’t immediately associate the term totalitarian with the idea that the state was turning people into automata (in fact, I can’t say I’ve had that many conversations with people where the phrase ‘totalitarian’ even came up: could be because I was only ten when the Berlin wall came down so it was less of a conversational topic?), so I think that was confusing me as well.

All that said, I have no problems whatsoever with your last two paragraphs above. I don’t see fascism and totalitarianism as being inextricably linked, and I’m also fine shelving the term “totalitarian” for purposes of this discussion.

Tor

LikeLiked by 1 person

Couldn’t find a relevant link so I have to rely on memory: literature and propaganda depicted people living in Warsaw Pact countries as beaten down, propagandized, and numbed. The intent may have been to raise sympathy for victims of Communism and, thereby, encourage acceptance of NATO policies. But that dehumanization also fits into a nuclear deterrence logic: given that potential victims of nuclear strikes have been so degraded and dehumanized, it’s not really that bad if they get incinerated in a war between West and East. Considering millions of people as one faceless horde — be it a pathetic or a menacing one — makes imagining bombs thrown against them a little easier.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I gave a lot of thought to this while working on Spione, as it was very difficult to get others to visualize citizens of the DDR as anything except wretched, bowed figures wrapped in rags, standing in food lines.

My thinking is a little different from yours – merely that it triggered the American horror of poverty, “you see what socialism does, it makes people poor.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. But you did get apocalyptic bravura from opinion makers. I came across one National Review piece where the writer said something to the effect that, given Christian eschatology and absolute moral principles, having the Earth depopulated in a righteous fight against evil is not the worst possible outcome of the Cold War. Fighting and dying to retain Christian civilization and going out as virtuous Christian warriors preferable to enduring slavery. The Yale grad’s fancied up version of “Better Dead than Red.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

My understanding of John Foster Dulles’ outlook was that it matched this view.

I suggested in Shahida that reactionary fundamentalism became transnational due to deliberate aid across borders/nationalities, and that this action is characterized by accord and mutual agreement among reactionary-fundamentalist Christian, Muslim, and Jewish power-brokers. (References: Karen Armstrong’s The Battle for God and Robert Dreyfuss’ Devil’s Game.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Part 3: I might as well finally define fascism then, right? The earlier points being that (i) it isn’t restricted to the details of historical examples and (ii) that I’m presuming it is a “thing,” actually happening, and not a chimera like the terms I described above.

Dictionaries are full of hassles for this purpose, but I think I’m staying in their collective bounds with the following description. Each of the entries below should be conceived as a spoke of a wheel; “fascism” is – as I see it – getting toward the center of the wheel such that the different components mutually reinforce one another. I’ll save the analysis for a final post.

Economic

This is the core: private industry retains its corporate financial identity, but specific corporate entities are so favored by the government, and so integrated with their functions, with key individuals passing back and forth, that they comprise a single power-and-policy structure.

The effect is that the state exists such that these companies profit, and these companies’ continued dominance is regarded as the health of the state. Legally it’s evidenced in non-accountability, via a tapdance between “but it’s the government, so regulations upon private enterprise don’t apply,” and “but it’s private, so built-in constraints on government don’t apply.”

Crucially, the funds are measured and evaluated (“the economy”) in terms of finance – given debt to use as collateral, who’s investing in it. It tangles up in three ways – the money value is converted into arcane indicators disconnected from their sources; no one can tell where Bank ends and Treasury begins; and the majority both comes from and disappears into international transactions rather than a domestic process. Again, the “health of the state” is identified with the continued flowing of these transactions, and these also comprise the basis for diplomatic alliances and policy collusions.

The necessary, constant extraction results in depression, middle-class failure. But since it comes in cycles, the next bubble provides an illusion of recovery and redemption, although upon inspection, and despite much advertisement, it applies only within strict socially-designated boundaries. (Crucial: this ‘spoke’ gets going long before the explicit hard-right political party gains government traction.)

Military policy

It emerges from the economics. The term “military-industrial complex” is extremely technical, especially considering that Eisenhower’s original speech included “-congressional.” Briefly, the government subsidizes businesses which directly serve the military, the local representatives make way for the businesses with easy-terms and other smoothing deals (re-zoning, etc), and the local populations’ employment environment is primarily defined by these businesses. The impact on every aspect of the local culture – – is a whole textbook of discussion, particularly the destruction of genuinely local industry which in a sane world would be called “the economy.” Employment goes up but nothing else does, and since this work is the only game in town, labor power evaporates.

An interesting detail: such employment is not at all perceived as “government” work, regardless of its dependence on public funding and on current government investment in military buildup. To refer to it as socialist (in non-U.S. parlance, “leftist”) would result in dropped-jaw stares.

A subtler version occurs in academics, especially the sciences, with a dramatic shift from basic/inquiry science to dedicated-aim engineering projects. The interplay among funding, influence, loyalty, and weapons development is really complicated, not as obvious as “we fund it so you’re loyal and you make our weapons,” and I can’t go into it in detail here.

The militarism more-or-less cannot help but be used eventually, considering how many people and systems are staked on garnering support by being “ready.” This leads to international bellicosity of the inch-by-inch, dare-you-to-stop-me sort, and also the incremental takeover of policy by those who discover ways to seize and override the nominal channels. Therefore actually going to war is a bit of a surprise to those who thought they were in charge of policy. The events are littered with resignations and with disgraces as people ended up talking past the point where they wanted to go.

Getting ahead of myself now, as this is a center-of-the-wheel topic, but the actual military action is always unbelievably stupid: it’s all shock-and-awe strike, good theater but strategically disastrous. Contrary to popular belief, the war once under way is already lost – it’s characterized by out-of-control, sadistic action on the ground, and by complete confusion and failure of basic goals at the management level. The effect is to do a lot of damage, to set up unstable puppets and call that “victory,” with literally zero local support – and then to be trapped in insurgent quagmires with no administrative capacity to get out. Notably, the vaunted military is crap against organized troops. It does great storming into a situation but supply and other organization is amateurish, falling apart fast. The troops are badly prepared for brutal, hands-on engagement and typically retreat in a rout. Most successes of this sort rely on puppet-government security forces instead.

Social psychology

This is easy, historically and verbally. The “fasces” is an object whose symbolism is quite clear. It’s about violent strength through many small contributors’ unity of purpose. It goes beyond the ordinary (I’d even say universal) concept of collective action, as each unit is not only unified, it’s uniform with the others, it’s interchangeable with any other such unit, and the “purpose” has only one quality: deadly force. There’s no nuance; it says what it means, it means what it says, and it happens to be fully accurate.

The symbol also requires – makes no sense without – an enemy. An enemy is easy to spot: it’s not uniform, it doesn’t contribute in the way each (“of us”) contributes, it’s necessary outside the bundle … if you’re aren’t part of it, then you suggest there’s some other option, and if you question it, well, by definition, you’re a threat. Socially, the designation of a fascist group’s enemies undergoes mission creep by definition. At first, you can’t disagree on essentials, then, you can’t disagree on current policy, then, you can’t disagree on any particular detail of comportment, and finally, you can’t disagree on any damn thing at all.

One important quality, to borrow a Marxist term, is the petit-bourgeois content of the avowed value-system, which is tied to the ethnocentrism I discuss below. No space to go into that here. Another, probably more important for present purposes, is the narrative of wounded virtue, resentment, “stabbed in the back” associated with the military. That’s tied to the elevation of military service to the society’s primary virtue, swiftly becoming fetishism both visually (uniforms, regalia, all getting a photogenic redesign) and verbally (no one says “soldiers,” but a long standard phrase instead).

Institional psychology

Obviously, the external or imposed aspect of fascism requires bigotry – technically, ethnocentrism, that you (as a type) are right and proper, meaning any details about anyone else will do to signify “other” – it could be religion, could be a physiological feature, could be a range of surnames, could be a given political label. Any such person, especially collectively, cannot possibly be trusted as part of the fasces. What they actually do or say means nothing; the very fact that they are here at all is an affront, an offense, an injustice.

Since the “us” is so strictly defined, relatively unrelated variables (opposing political party, ethnicity, religion) are confounded to make any “other” a single threat. This permits easily-targeted groups to be lumped in. They can be abused safely, blind toward the fact that one is picking on the least-able to fight back but yet feel as if a terrifying social menace has been necessarily confronted.

I’m including it under this category because it’s not the mere individual attitude which serves as a partial defining feature for fascism, it’s the institutionalization of the attitude, its role as the “new normal,” politically and professionally rewarded as such. Therefore discriminatory policies, or worse, may be regarded much like public effort toward common hygiene. Significantly, at this level, discrimination (or worse) can easily be directed toward state-designated targets, rather than merely conforming with grassroots ones.

I dunno where “nationalism” ends and “statism” begins, or if they’re the same thing, or what. Whatever that is, turn it up to 11, such that this particular organization and policy effort is hailed as both inevitable and at-risk – and it swiftly becomes a religion in every sense of the word. Durkheim would love it: celebration and demonstration of “our nation,” “the country,” “the homeland,” et cetera, is a constant feature of social life. It receives incredible institutional support, again at a non-membraned, conjoined interface between government and private, focusing directly upon the military and sports.

To me, it’s most evident in the frequent flatly-illegal, blatant maneuvers of various state and industry actors. No established or written feature of the law – and remember, this is from an ideology purporting to restore “law and order” – is safe from simple violation, often using particularly childish logic which amounts to brazening it out every time. The public acquiescence to such things, even their enthusiastic acceptance by some, treating these un-representative, un-legal, and often nonsensical events as the new normal.

Not that such events have no purpose – they uniformly diminish the power of unions (the union might continue to exist, but as enforcers for the employers, not as collective bargaining for labor), and to co-opt media of all kinds. To say that publishers and producers become mouthpieces for state policy is simply true – it’s not hyperbole.

Contrary to popular usage, I don’t think the specific personage of “the leader” is causal in fascism, rather, he’s strictly an effect of the bigotry and statism reinforcing one another. He’s always catapulted into prominence through some appropriation, rather than being an effective organizer or political animal. His buffoonery is real and widely recognized and commented upon. I even think he’s not technically a dictator, as rule is conducted by a cynical gang of insiders for whom the leader provides cover. Tracking the leader’s unpredictable pronouncements with their machinations is fascinating as they try to capitalize on some things and to paper over others.

He is, however, undeniably a demagogue. It’s impossible to tell whether he’s taking cues from his supporters or vice versa; perhaps no one knows. His absurdity is actually a source of strength – the most fervent supporters feel very humiliated and “loser” ish, so the more critics mock the leader, the more angry and justified the supporters feel in resenting them, adopting the absurdity in defiance. The more angry and out-of-control the leader, the less willing or even able he is actually to do any sort of job of governance, the better to focus the fuck-you, yeah-we-suck, what’s-it-to-you, you-egghead-above-it-all orientation of public support.

Security, policing, oppression

This is a biggie, maybe even more so than the militarism. There’s a heavy police presence with new, expanding special security and law-enforcement powers, directed hard at subpopulations deemed not quite right enough, and undergoing unsubtle mission creep. THe extremity is always pretty shocking – the degree of brutality, reach, overstepping, presence is way past what anyone would have imagined possible … and crucially, accepted.

Related, but not synonymous, are the militarization of the regular police, and the ramp-up of new branches and departments of political police. The latter are openly and straightforwardly directed to “thought enemies” of society – those who haven’t done anything but are considered ripe for doing so at any moment.

Related and synonymous, however, is the presence of thug movement support from the populace, which is not only tolerated by law enforcement, but fully complicit with it. Mob action is literally a police weapon; police action toward the mob is openly protective. Standard protests and demonstrations have no chance: the mob attacks while the police stand aside; the police attack and the mob backs them up. Such movement suppport is widespread enough that it becomes a wing of the government (or one of its many bewildering departments and divisions), psychologically preserving its “we’re just citizens” autonomy. Many of them become named militias with government-issued equipment.

I’ll tell you what’s not the case, however: true uniformity of support among the general population, not even among those deemed “all right.” Most everyone goes along just enough, referring to current events as an aberration, poking fun at the events within acceptable bounds, all the while buying in more than they think they do. To these people, there are consequences for less-than-perfect ideological purity but they’re generally not eligible for open abuse. And those who get too visible undergo severe career and other social marginalizing, quickly becoming unpersons although they’re not arrested and/or murdered.

One last, crucial: these “spokes” get under way long before the party identified as “the fascists” actually wins anything or takes power in governing terms. When it does, everyone is flabbergasted, including them, especially since the prior history includes a series of what look like crushing popular or electoral defeats. What’s happened is that the nominally liberal or centrist parties, and balancing mechanisms, have instituted a great deal of the above spokes quite a ways toward the wheel’s center, before the ranting buffoons show up to grab hold of it, as if it had been prepared just for them.

As I mentioned above, there’s a part 4. Thoughts on this part first?

LikeLike

Hey Ron,

Wow. Give me a day or two to absorb this and formulate a response.

Tor

LikeLike

I went ahead with the next step below, but I do want your thoughts on the above post too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ok. This is a great description, and jives extremely well with my own built in understanding of what fascism is. I’m also trying to read this without reflecting too much on the United States in order to keep an open mind, but it’s hard not to.

So my one question/comment at this point is, isn’t it fair to say that any society is going to exhibit these symptoms to some extent? Governmental favoritism of certain private corporations, the targeting of ‘others’, factions looking to push militarism and profit from it? And doesn’t that make the definition too broad (as in, all governments are fascist)?

– Tor

LikeLike

That alerts me to clarifying something. I didn’t write a bit of the above post with reference to the U.S. It’s taken strictly from descriptons and definitions of designated fascist regimes.

Two points. First, I specified that I’m referring to the confluence and mutual reinforcement of all those components. No single one of them is atomically fascist.

I do think the confluence, once under way, takes on extremely recognizable features. It’s pretty hard to think “fascist” without imagining some puffed-up baboon in an oversized military hat, a fired-up, murderous crowd, a sinister coterie of brutal semi-police, and an immediate military assault in action. But that’s all right, because for some reason, once at the center of the wheel, that set of outcomes is apparently pretty damn predictable.

The point being that identifying this or that component in some other society is not a fascist atom or “tell.” One has to decide when the confluence is strong enough to define the term, which I leave to the experts. To look below to my point #4, Jaspers focuses on the collapse of factional debate – specifically, the elevation of centrism as ideal policy – as the key causal moment or event. As a non-expert, I tend to focus on the “paper” quality of many of them as a key observation, in that they have to mutually-reinforce as none withstands critique. You asked about both of those points below so I’ll talk about them there.

Second, I think history provides some interesting other ways to have done things, not in some dramatic alternative sense like “real communism in antiquity” or whatever, but with many of the same features, but organized differently, or with a single core difference, such that the “wheel” never forms. I’ll talk more about that further down as well – probably at the end, still a major post or two away.

LikeLike

Okay, great. That’s very helpful.

LikeLike

Part 4: Analysis.

I recommend Karl Jaspers’ Wohin treibt die Bundesrepublik? (American title: The Future of Germany), published in the late 1960s. He wrote it to warn against the dangers inherent in a centrist coalition … that may not make much sense in American terminology, so I’ll translate it to liberal-conservative alliance, or as it’s often spun, “bipartisanship.”

The following may be too abstract a summary; let’s see. OK, speaking not of psychological attitudes but dedicated collective effort, let’s run a spectrum from Revolutionary, Reform, Liberal, Conservative, Establishment, Reactionary. It’s linear, not a horseshoe. See those two in the middle? They’re pretty much alike. They operate within a designated system of negotiation, and for the most part, their differences are best described as “let’s change it a little more” vs. “let’s not change it just yet.” I won’t break down the details among the two “harder” options on each side, but will stick to this point: that the two on the right (Establishment, Reactionary) are able to “hide” within a nominally conservative political effort, especially when police work and armed service are identified as specially patriotic; whereas the two on the left (Revolutionary, Reform) are much more visible for what they are, and easily targeted – and demonized as disloyal when they criticize the police and the military.

Another way to put it is, the Liberal contingent may not like or want to be associated with its “harder” cousins, but without them in play, if only as a threat, it has no muscle to negotiate with the Conservatives, and has no choice but to ape them and in effect merely to increase the Conservative contingent with a guise of opposition. And all the while, the more extreme rightward contingents are growing in effective power, without the hard-leftward contingents (who do not fear the electorate) to call them out, or to meet them in the streets. If this isn’t stopped by a dedicated organization – i.e., if the leftward contingents are successfully made taboo – then the entire government class becomes dedicated to scrambling to prove how orthodox (patriotic) it is, by throwing the Establishment and then the Reactionary contingents as many concessions as it can. The entire government becomes nothing but a Reactionary surge toward empty-headed chaos while the most cynical Establishment players loot it blind, and while the former Liberal+Conservative contingents maunder and waffle about why can’t they be in charge. And by that point, not conceding to the Reactionary contingent is not only political suicide, but incurs genuine physical threat too.

(It may help to think of an American “party” not as a party at all, but as a monetary focus for forming coalitions among these sorts of efforts, such that a given named party represents very different coalition at any given moment. I’ll bite my tongue to avoid going into a long discussion of coalition parliamentary politics.)

(You can probably see that I’m not even bothering to dismiss the terms “liberal” and “conservative” as they’re mis-used and debased in U.S. parlance. For example, what I’m calling the Conservative contingent here is best represented, currently, by most Democrats and what are derisively called the RINOs.)

So briefly: a centrist coalition opens the door to the isolation and demonization of the leftward contingents, and soon only theatrical and ineffective versions of them remain; meanwhile the rightward contingents become the real power-players under cover of false debate and essential blending of the two centrist ones.

You see how this runs counter to the modern dogma, right? According to that dogma, factionalism is bad, coordination at the center is the solution, and the goal is apparently for everyone finally to know, to agree upon, to want, and to act toward a single societal vision. See his point? Centrism is fascism, socially and philosophically. All that remains once that’s under way is for the hard-righters to step into the prepared space.

His book isn’t so abstract though. He carefully describes the incremental way this occured in 1920s and 1930s Germany, especially the subornment of labor, the flip in media support, and the shift among public intellectuals which they seemed unable to perceive in themselves. I had not read it too long before I visited the History of Berlin Museum, where the same period is presented in exquisite detail as you descend a staircase, and I was amazed at how well he’d summarized it. Experiencing that exhibit was like reading his account through a higher-focus lens – and crucially, it shows that such effects are not due to same vague and cause-free “national mood” or “shift in public opinion,” but engineered by relentless, precise moments of administrative bullying.

My addition to Jaspers’ analysis is, as I couldn’t help but jump the gun on in my #3 post, is to highlight the bubble quality: the alleged prosperity and recovery, the house-of-cards war financing, the alleged awesome military, the alleged restoration of law and order, the alleged overwhelming popular support. It’s all papered over at the time with dumb phrases that everyone seems to believe, but it’s painfully obvious in retrospect. No one thinks otherwise about Italy, and the only reason we don’t say it about Germany is that the myth of the “unstoppable” foes we stopped from “taking over the world” is too valuable.

That’s why I think fascism as usually discussed, focusing only on the gaudy end-stages of specific instances, is not a system or social organization at all, but the predictable actions of profiteers and thugs in the positions of power they’ve managed to grab, following the prior tacit breakdown. That’s why those actions only make sense as far as profiteering and thuggery go, and in terms of governance, economics, and military action, they’re spastic and destructive internally as well as externally. That’s because government, economy, and military in any organized sense of the term, are already long gone, and these guys are in it for the loot, with one or two exceptions who apparently believe their own bullshit. This train-wreck endpoint doesn’t really interest me. I’m interested instead in that prior process, which is characterized by self-congratulatory democracy, e.g. rapid party re-organizations and dramatic electoral campaigns purporting to “go one way or the other” with no actual change in policy, and most especially, by the apparent dominance of what’s termed the moderates, or centrism.

To repeat Jaspers, I think that phase is not “a struggle against the darkness,” but is rather its onset, during which social reform is characterized by symbolic, articulate rhetoric, but is completely non-substantive, and whatever representation the nominal democracy provides is scrubbed away. The police repression, the military build-up (and concomitant decrease in military sense), the institutionalization of racism, all ratchet up way before any “glorious leader” is thrust into the limelight. Coincidentally this recent article isn’t too bad a look at that: Cannibal Corpse.

… annnnd, sure enough, there’s a part 5, to talk about the U.S. Last one, or maybe not. Thoughts on this first? I think it’s finally getting at what you asked about.

LikeLike

Okay, a ton of questions. So many questions. I’ll dive right in.

“let’s run a spectrum from Revolutionary, Reform, Liberal, Conservative, Establishment, Reactionary. It’s linear, not a horseshoe. See those two in the middle? They’re pretty much alike. They operate within a designated system of negotiation, and for the most part, their differences are best described as “let’s change it a little more” vs. “let’s not change it just yet.”

So good. I don’t know why, but I’ve never seen the range of political positions laid out like that, and that’s weird, because it’s an incredibly clear and useful way to think about it.

“whereas the two on the left (Revolutionary, Reform) are much more visible for what they are, and easily targeted – and demonized as disloyal when they criticize the police and the military.”

Oh my god, yes. That makes sense and helps to explain the imbalanced way far left and far right gets talked about in our society. This has been bugging me for a long time, but your comment makes perfect sense.

“Another way to put it is, the Liberal contingent may not like or want to be associated with its “harder” cousins, but without them in play, if only as a threat, it has no muscle to negotiate with the Conservatives,”

Is this symmetrical? I mean, can you swap the words ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ in the above statement, or is it asymmetrical as in your comment that I quoted above.

“and has no choice but to ape them and in effect merely to increase the Conservative contingent with a guise of opposition. “

Okay, I don’t understand this. The liberals have no choice but to ape the Reformists and Revolutionaries? And why does this increase the Conservative contingent?

“And by that point, not conceding to the Reactionary contingent is not only political suicide, but incurs genuine physical threat too.”

Ah, yes. This sounds familiar.

“(You can probably see that I’m not even bothering to dismiss the terms “liberal” and “conservative” as they’re mis-used and debased in U.S. parlance. For example, what I’m calling the Conservative contingent here is best represented, currently, by most Democrats and what are derisively called the RINOs.)”

Okay, so to be clear, the scale you described above doesn’t have to do with specific political positions, only with how you relate to existing systems of power? So US Democrats are “Conservative” because they essentially defend the status quo with some concessions to Liberals and Reformists?

“So briefly: a centrist coalition opens the door to the isolation and demonization of the leftward contingents, and soon only theatrical and ineffective versions of them remain; “

Hopefully your answers to the above will help illuminate this for me.

“You see how this runs counter to the modern dogma, right? According to that dogma, factionalism is bad, coordination at the center is the solution, and the goal is apparently for everyone finally to know, to agree upon, to want, and to act toward a single societal vision”

I’m starting to see. Here, let me take a shot: because the political spectrum functions asymmetrically, meaning the far left operates under more scrutiny and criticism than the far right, a coalition between the center left and the center right especially hurts the far left.

“where the same period is presented in exquisite detail as you descend a staircase, and I was amazed at how well he’d summarized it. Experiencing that exhibit was like reading his account through a higher-focus lens – and crucially, it shows that such effects are not due to same vague and cause-free “national mood” or “shift in public opinion,” but engineered by relentless, precise moments of administrative bullying.”

Sounds like a pretty awesome museum.

“My addition to Jaspers’ analysis is, as I couldn’t help but jump the gun on in my #3 post, is to highlight the bubble quality: the alleged prosperity and recovery, the house-of-cards war financing, the alleged awesome military, the alleged restoration of law and order, the alleged overwhelming popular support. It’s all papered over at the time with dumb phrases that everyone seems to believe, but it’s painfully obvious in retrospect.”

I think I get this. Can you think of an example of a ‘dumb phrase that everyone seems to believe’?

Also:

“No one thinks otherwise about Italy, and the only reason we don’t say it about Germany is that the myth of the “unstoppable” foes we stopped from “taking over the world” is too valuable.”

So the Wehrmacht wasn’t an awesome military power? How did they mud stomp all of Europe less Britan then while taking on Russia?

“but the predictable actions of profiteers and thugs in the positions of power they’ve managed to grab, following the prior tacit breakdown. That’s why those actions only make sense as far as profiteering and thuggery go, and in terms of governance, economics, and military action, they’re spastic and destructive internally as well as externally.”

This makes sense. Can the thugs and profiteers be elected officials? Can they also be non-elected people in power (like bank executives, or corporate CEOs)? Are the thugs and profiteers distinct in ideology and methods from other politiicians or people in power? I mean, can you point at Mike and say, ‘he’s a thug’, and then point at Jean and say, ‘she’s just a regular ol politician’?

I’m feeling like this is actually the in-depth answer to my original question, which was why you don’t you talk about Trump in your blog.

– Tor

LikeLike

I’m pulling this question out of order, to the front, because it matters so much.

Absolutely correct. You have understood me perfectly. I’m talking about democratic government, of nearly any type or organization – anything in which avenues of representation are present and dynamic.

I should also point out that, as with the definition of fascism above, it is not derived from studying the U.S. either. It’s taken strictly from my study of coalition democracies (parliaments), the most common version in the world today. I also think many, many historical cultures qualify in this category without modern acknowledgment. Therefore I only mentioned the current U.S. terms in the post in order to dismiss them.

Oh yeah – this construction is authored by me; it’s part of my book/game in development, working title Amerikkka. I am heavily influenced by what appears to be the unspoken “everyone knows” use of these terms during the late 19th and early 20th century, but I know of no source from that time which sits down and defines them. (And nearly anything after WWII is basically blither.) For example, Jasper – whose views date from prior to WWII – uses them as unspoken givens, not in these terms or in the explicit construction I laid down.

When I do apply them to the U.S. it works beautifully, but only if you realize that our rhetoric and overt democratic processes, e.g. the named parties, mask the dynamics that are more visible elsewhere.

LikeLike

In this case, yes, it’s symmetrical. But it’s also highly specific to the topic at hand: seeking to preserve a substantive debate between Liberal and Conservative, while each one is still powerful and relevant enough to wield actual power.

As long as this is a real debate, i.e., centrism isn’t being sought, then government in this circumstance can actually, you know, govern – alternative policies get debated, votes get integrated with policy-making, and a policy gets hammered out which probably annoys a lot of engaged participants, but which most people in the larger population, even those with opposed interests, are OK living with.

Therefore the idea that the Liberal contingent “needs” the presence of Reform and/or Revolutionary, and the Conservative contingent “needs” the presence of Establishment and/or Reactionary, is not due to affinity or shared goals, but as unused threats by Liberal and Conserative in order to keep strong hands against one another.

As a related and important point, one thing that emerges from this analysis is that being adjacent doesn’t mean “has affinity,” quite the opposite in fact. So there is no overriding “unfied” Right or “unified” Left that can be defined as a goal or specific kind of effort.

Remember that I’m specifically excluding Reform from Liberal, and Establishment from Conservative. In this construction – Jasper’s ideal – those two contingents are fervently attempting to take over the center two at all times but are forced to play nice in coalitions instead. Thus their positive qualities can be extracted for policy-making and their negative ones can be left for hard-liners to grump about in their Reform newsletters and Establishment lodges.

Jaspers’ argument is that in such a circumstance – which I suppose you might as well call “democracy” if you don’t mind the imprecision – then we may see some bad policies and we will certainly have to put up with many outrageous claims and demands, but we may often see very good policies. Most people are at least being heard, radicals of all sorts can throw their intended monkey-wrenches into the mix without much chance of genuine disruption (and a really good idea can gain traction), and we will not spiral into fascism. The Revolutionaries and the Reactionaries will be pissed-off most of the time, but even they will get their way in small things more often than they think.

But outside of that specific topic, every contingent is its own powerful avenue or approach to political action, with relative amounts of power (let alone representation, population-wise) being a matter of historical moments. When it comes to impact, whether votes or bullets or covert action or narrative-building, none is intrinsically more effective or important than any other.

LikeLike

Whoops, you misunderstood me there. The Liberal effort has no choice but to ape the Conservatives, or risk being demonized along with the harder-line leftward contingents. If centrism is the ideal, then the isolated Liberals are disadvantaged now – they are vulnerable to cries of “you’re not playing nice, you’re being radical, you’re being partisan, we knew it all along.” Since the Liberal effort has to maintain their agreements with the Conservative in order to be part of the power structure at all, it’s no surprise that very soon, as few as one or two election cycles, the Liberal position is swiftly indistinguishable from the Conservative one except with a few more smiles and nods. (And the Conservative one is now a bear trap containing powerful Establishment and Reactionary efforts under “moderate” “we’re all [insert nationality] here” guise.)

Let me know.

LikeLike

Yes. However, again, only if we’re restricting the topic to how strong Liberal and strong Conservative efforts interact, when making actual policy through substantive debate, and how fascism can be understood to arise without reference to gaudy personalities and pathology. That’s Jasper’s highly specific topic in his book, but I like to think about the larger picture for which this is just one circumstance.

For example, Jaspers’ viewpoint isn’t sympathetic to the various points or positions held by Revolutionary or Reactionary that might, you know, have a point. He only acknowledges those insofar as snippets of them filter into the more central positions, which he sees as positive. Therefore he’s very supportive of the idea that society includes vocal, intense, potentially even violent political efforts – but is trying to find a way for the Liberal and Conservative efforts to be the most powerful, representative, and policy-making ones. I think his point is very good toward that end – that you get that result when those two efforts do not seek agreement, and especially not make a formal “we shall agree and co-govern from now on” deal.

However, his analysis – perhaps necessarily, for his point – seems shallow to me in terms of regional identity and economics, throughout an area. There are policy debates for which who is the winner or loser is going to be strikingly different from region to region, and for which highly generalized, broadly-sourced compromise really isn’t the best answer, and for which the loser isn’t going to go along nicely.

He also seems a bit naive to me in terms of just how much assassination, mob violence, propaganda, and intimidation occur in non-fascist democratic processes, both within government and out there among the populace, and at the service of any of the six efforts whose proponents happen to feel they wouldn’t get their way if everyone voted at the moment.

LikeLike

“Mussolini made the trains run on time.” This one illustrates the power of such a statement both at the time and for later historical narratives, i.e., it’s still popularly stated.

He, or rather, that regime, did no such thing.

LikeLike

Sure. It’s important to my whole construction – and you can see it from my first responses – that democratic terms and processes do not comprise a category that excludes the category of fascism. It seems intrinsic to Jaspers’ point, too, that various democratic forms and even processes are still in place well after actually-existing fascism is in place.

Therefore “thug,” “profiteer,” “politician,” and “elected official” are separate concepts but potentially overlap in any combination. Mike’s a thug, Jean’s a politician, and Bob’s both, and Martha is neither but is a profiteer, and Sam’s both a profiteer and politician, et cetera. I guess I see their separate definitions as easily parsed, especially when we’re not talking about motives to infer, but straightforward and observable actions. Don’t forget the extensive grey area of appointees, too, who are not elected but are in place due to an elected person’s power. If “politician” means “policy-maker,” then man, any of them can be a politician.

LikeLike

It is. I actually set it up – or wrote enough to salve my sense I should say something – in the post itself, which you picked up on. I’ll get to the specifics about that in the next post, about whether and how these notions about fascism apply to the United States.

I’m also holding off from replying about the awesome unstoppable insurmountable Wehrmacht. I typed a whole ton actually before realizing how many sacred cows I was not only shooting but desecrating. Let’s save that for later – it’s not really a detour but will make more sense after the next post, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And……. this is why I read this blog. I’m fine to move on to the much built up and equally anticipated #5, but I do have a few comments and questions (as I write this fireworks go off in the distance and someone is playing the national anthem as part of July 4 festivities).

– Is there any connection between the various positions of the political spectrum (Revolutionary, Reform, etc) and moral right and wrong? Or, maybe that’s a bad question, how about this: have you thus far implied any such connection? This may sound like a weird question but I have reasons for asking.

– When you said “I am heavily influenced by what appears to be the unspoken “everyone knows” use of these terms during the late 19th and early 20th century,” are the terms you are referring to “Revolutionary, Reformist, Liberal, Conservative, Establishment, and Reactionary”? If the answer is yes, then I’ll feel a lot better about my life long confusion about what exactly these terms mean, in spite of hearing them ALL THE TIME.

– This: “In this construction – Jasper’s ideal – those two contingents are fervently attempting to take over the center two at all times but are forced to play nice in coalitions instead. Thus their positive qualities can be extracted for policy-making and their negative ones can be left for hard-liners to grump about in their Reform newsletters and Establishment lodges” is hilarious and tremendously useful.

– It sounds like you are saying that a healthy and just democratic society will benefit from, and possibly even need, citizenry who represent all of the various positions (“Revolutionary” etc). Is this what you’re saying? That Reactionaries in small amounts can be/are good for society? (maybe you are saying that here: “For example, Jaspers’ viewpoint isn’t sympathetic to the various points or positions held by Revolutionary or Reactionary that might, you know, have a point”?)

– As far as dumb phrases go, “made the trains run on time” seems to be the most famous, how about “Hitler fixed the German economy”?

Okay, that’s all. Ready for #5.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Answering your better construction: no, I have not implied any such thing.

However, I will also say that to the concerned individual, stuck in a policy-situation (which is to say, living in society), for which these approaches are present not as abstractions, but as deeply historical and highly-coded actual events and rhetoric, with actual policy consequences on the line, the exact coalitions among the approaches, at this moment, will be inextricable from this person’s moral right and wrong. Completely understandably and perhaps intrinsically.

It’s “yes.” As far as I can tell, following the 1940s, the terms became so tied to their local applications in U.S. and Cold War policy that they swiftly lost their generic meanings. It’s also important to see what happened to them in the late 1980s, when they shifted from merely compromised and confounded with specifics, to genuinely incoherent.

For a very good, quite precise example of solid post-WWII and pre-1990 usage, see Puh-leeze! for my discussion of the Red Skull’s mind-control of the Falcon in the mid-1970s.

It’s tough to stay clear about when I’m (i) paraphrasing Jaspers’ points about centrism and fascism, I hope correctly; (ii) framing them in my larger-scale thoughts about these approaches and democracy, outside his specific topic; and (iii) stating my judgment about virtues and limits of his argument. In this case I’ll stay with (i).

I think Jaspers’ goal is simple: “How do we avoid fascism?” He doesn’t state an ideal-oriented goal about healthy, just, and democratic, he’s merely starting with existing forms of democratic as a given and talking about a particular potential outcome. I happen to find this down-and-dirty perspective appealing, especially since it’s very rare among post-WWII philosophers.

To extrapolate or interpret slightly, I also think – or infer from his text – that these approaches are phenomena that exist. Given a political process in which representation and voting play a part, they all kick in hard as features of society. (Remember, he doesn’t break them out into six “entities” like I did; it’s just that his phrasings and the dynamics he described fit nicely into the entities as I’ve summarized them myself.) Given that, it’s not a matter of “need” or “should,” it’s simply that this is what society looks like, and moving on from there.

LikeLike

Part 5. It’s probably obvious by now that I consider U.S. political culture to have become fascist long ago, i.e., enough spokes far enough into the center, mutually-reinforcing enough, and with enough emergent effects. I concede that another person might have a different “enough” threshold, such that they’d state a different date, or state that we’re not there yet, but I do not think the processes and effects are much in debate. The trouble lies not in the argument but in directing people’s attention to it.

Since it’s a multi-spoked wheel, I provide no single date, but I think core features are easily found in the National Security Act of 1947, in George Kennan’s White Paper of 1948, and in the remarkable collusion of state, espionage, and corporate power represented by the Dulles family by 1952. I recommend examining the election rhetoric of 1948, the first time that the two primary political parties of the U.S. fought to own the same policy position, i.e., not offering a policy choice at all. Until that point, the Democratic position was to fight “enemies abroad,” specifically communists, and the Republican one was to fight “the enemies at home,” ditto. By the election in 1952, both parties were explicitly committed to doing both, and the only electoral issue was which one was doing it/them the more fervently.

I point especially to how the technique of replacing union leadership with right-wing mob and business collusions, developed in Italy just after WWII, was imported successfully to the U.S. and implemented in full by 1953.

Another significant moment was 1972-1978, when the U.S. was bankrupted by the Vietnam War and its economics were shifted to be defined strictly by credit for international finance. Domestically the impact was immediate – no recompense for production at all, the flatlining of wages which persists to this day – and later, austerity, which was initially used as a weapon against Allende’s presidency in Chile, and is now rebranded as domestic and EU policy. As long as we’re talking about electoral moments, I recommend examining the Democratic Party’s destruction of the McGovern campaign and the resulting invention of superdelegates; you’ll have to look well past Wikipedia. This period also includes the loss of even the illusion of criminal accountability for the president and associated positions, the skating of the intelligence agencies past exposures that should have scuttled them entirely, the instigation of the War on Drugs and the expansion of the Texas prison system, and the first appearance of explicit belligerence (i.e., no longer “who us? what warmongers?”) as the defining virtue of foreign policy.

I trust that it’s not necessary to dissect the creeping militarism throughout the second half of the 20th century, beginning with covert ops and U.N. action as cover, then shifting into unilateral action, first with little missions and eventually into bombing campaigns and full-scale invasions.

Nor should I really need to go into the more-and-more high-impact collusions among finance, insurance, and real estate. I stress that as with the military policy’s it’s been a steady creep regardless of specific president or political party.

By contrast, it may take more effort than I have available to convince some readers that the liberalism that they’ve prized as “progressive” (meaning Reform) for the past thirty years isn’t Reform at all, or even Liberal, but has been hand-jobbing the hard right the whole time. I call attention to (1) gay being OK after all – once they’re shown to be properly committed to military service; (2) much yap about a woman’s right to choose while actual birth-control and abortion services disappeared from most of the U.S., especially for anyone under median income; (3) astonishingly blatant black show ponies, assimilationist to the core, held up as evidence for the disappearance of racism – while the prison system re-instituted ethnic slavery nationwide and the police became a militia, including bare-faced banditry and ethnic-cleansing assassination.

For similar reasons, I’m not going to provide the necessary many-thousands word essay to clarify what the Reactionary really is, here and now. It would begin with a good airing for the term “white,” and the realities the term obscures in all directions. A post someday perhaps. Even the most radical only sort of get it: The cultural anxiety of the white middle class and The racial mythology of the Left’s political nostalgia; I’m citing them now because the latter ties well to this discussion’s topic.

I had my personal “all right, that’s the corner turned” moment. Some time in 2006 and 2007, reading Jaspers and thinking about that exhibit in Berlin, I decided that whenever it might have been clinched as a process (1980? 1996?), the deal was sealed – i.e., the process had invited in those who would truly use it – when Dick Cheney set up his own White House Staff.

That’s a very technical statement so I should clarify. On paper, according to the National Security Act of 1947, the various intelligence agencies were all supposed to run their findings through a central node for final analysis, hence, “Central Intelligence Agency.” It wasn’t to have any other function. However, this agency turned out to have its own surveillance and operations programs as an artifact of last-second finagling, e.g., until 1958, the operations branch, or Office of Policy Coordination, was semi-pseudo private and actually not officially part of the CIA (and had its own back door into the Treasury for funding). The operations director of this … thing, Allen Dulles, became the head of the (real) CIA in 1952, and that pattern was often repeated after the OPC finally did get folded officially into the CIA. This person was also, as part of that job, the representative of U.S. intelligence (National Security Advisor) at meetings of the National Security Council, as per the actual-on-paper mandate of the CIA.

Real players in the history of the Cold War U.S. knew that this whole arrangement – basically a direct line from the Security Council into CIA covert ops, and back up, was a source of incredible real power. From the top, you could run operations that were tailor-made to justify the policy you wanted, or you could run operations without policy at all and dare anyone to stop you; from the bottom, you could force policy-makers to live with what you just did … it bypassed every on-paper, organized form of governing, and existed entirely free of oversight or law.

Now, exactly who grabbed that lever at any given moment is a matter of raw history. You’d recognize a couple of the names easily and not a couple of the others. But what I really want to talk about is how a number of employed positions evolved during the decades, associated with that chain of power, and like all shady bureaucracies, taking on a policy identity of its own. This is the so-called White House Staff, whose name might lead you to think of people dusting china or setting up PowerPoint for visiting school groups, but is actually a terrifyingly significant policy culture, and since it’s not actually a named intelligency agency, is completely free from oversight or accounting. Thus the White House Chief of Staff is a grossly powerful person who, historically, has not been above seizing that lever himself.

In 2000, Dick Cheney did something only a very canny, knowledgeable insider could have done – he not only seized the lever, but also set up his own, independent White House Staff, de novo. This is why he and a number of cronies could insert short-lived “replacement” agencies right over the DIA, the CIA, and the NSA, each of which stovepiped any snippet of un-analyzed intelligence (i.e., rumors) to his office. Those, as you should know, became leaks to compliant media, then the media reports were used as an excuse for the White House to be “forced” to respond. (This is addition to the new Department of Homeland Security, which was set up to report and function directly under the White House, rather than the Department of Justice like the FBI.)