Doctor Venn’s circle strike

It’s true that a lot of Venning is nothing special, an unnecessary display of things that do just as well in a comparative table. It also risks reifying, thereby generating categories as “things” when none exist just because you depicted a circle or box.

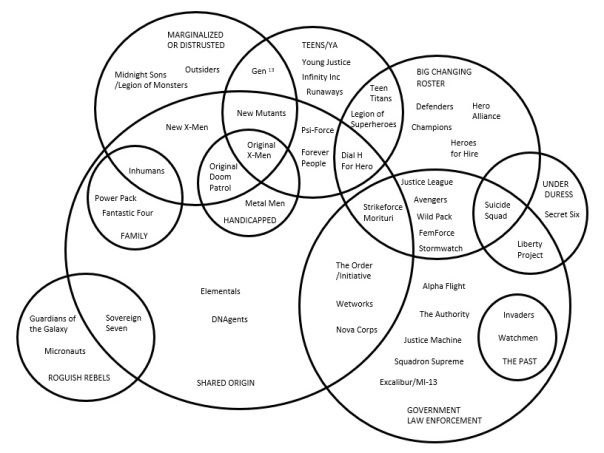

But here I am working on a game system which lets people make their own superhero groups for their own creative purposes, rather than aping existing ones, and yet also which relies on inspiration from and appreciation for the comics. How does one describe and inspire superhero groups without just skinning existing ones? I started thinking about what superhero groups were and why they existed – not the in-fiction reasons, but reader and publication reasons.

Historically, superhero groups are a great way to sell one more comic without making up anything new, to keep IPs active when they can’t carry their economic weight by themselves, and to pad pages with lots more banter and dialogue and poses than you can get away with in a single-protagonist story. I am cynical enough to think that’s all the explanation we need for why they exist in the originalist/source version of that question.

But that did and does lead to a variety of engaging creative opportunities and questions which at least some comics creators picked up on, at least some of the time. I’m tentatively proceeding under a non-cynical, not-very-secure hat of hope that those efforts produced categories that might provoke creativity.

This is a first pass, anyway, and it’s certainly casual if not outright careless.

My choice of “handicapped” is probably getting glances, insofar as I think one of the strengths of the original Metal Men is that each hero was so strongly characterized as to be borderline-clinical, albeit written in a charming and “sometimes that’s what it takes” way.

The original Champions game (not the Marvel comic of that title) was profoundly inspired by comics from about 1965 through 1980, so I’ve focused on groups from that period or which came up a little bit later by the same creators or younger creators who were clearly working from those models of comics storytelling. I definitely think it’s a bad idea to dump in every imaginable group, e.g. from the Wikipedia superhero teams page.

I’m staying away from movie and recent franchise concepts, so a lot of the re-conceived versions of the Avengers or the Champions aren’t in there. I decided most spin-off groups aren’t really their own things, especially the plethora of X-titles which would do nothing but fill up the space occupied by the New X-Men. I also tried avoid blatant reboots and also deconstructive expys like the Hero Alliance or the Authority. Maybe some of those are worth including, I don’t know.

Even now, a couple of groups of groups occur to me which are conceivably interesting or would cause some circle-shifting. Strikeforce Morituri and several of the Wildstorm groups would be found in an overlap between “shared origin” and “government/law enforcement,” for example, which doesn’t ruin the overall arrangement but brings the two lower circles closer.

At the risk of that reification thing, one of the empty zones does strike me as begging for it: the “teens, feared and distrusted, but not shared-origin,” or its mirror, “teens, shared-origin, but not feared and distrusted.” I must just be missing

As with any multivariate method, this one benefits from holding back on some variables of interest and then assessing their distribution across the pattern you get from the numerous, concrete, and not very interesting ones. In this case, I was interested to see whether any characteristic villainy or politics arose in adjacent sectors, and it does strike me that betrayal, either by a rogue member or by an authority figure, seems concentrated over to the right, and antagonists with at least some right or reason on their side seem concentrated over to the left.

Another way to look at it is to treat the arrangement as entirely historical and contingent, thus indicative of nothing special, and permitting “violation” in order to think of something new with previously unmined story potential. I find myself resisting slightly when I try it, though. Teens under duress by law enforcement? Maybe, if a bit grim.

And finally, the variables strike me as awfully limited. There are probably plenty of founding concepts to work with which remain surprisingly untried. Maybe there’s lot of room for new superhero team creativity, rather than rebooting and deconstructing the few arrangements that happened to show up so far.

Posted on January 18, 2019, in Heroics and tagged superhero group. Bookmark the permalink. 18 Comments.

A more useful classification system may be multidimensional, with several axises of definition, each with a continuum. (Like the Traveller world generation system).

For example:

Origin:

1- Family unit, shared power origin (FF, Inhumans)

2- Shared origin event

3- Similar power origins (all mutants, all magic users)

4- Same origin genre (all super-science, all supernatural)

5- Eclectic power origins (The Avengers)

Legality

1-Government controlled

2- Government sanctioned, but autonomous

3- Government contacts

4-Works within the law

5-Outlaws

Geographical area

1-Works inside a single city

2-Works in a small region (a single state or province)

3-Works inside one country

4-International

5-Interplanetary

Power Level

1-Trained human

2-Trained humans with special equipment

3-Innate powers equal to military/police units

4-Innate powers equal to military operations in strength

5-Innate planet-busting powers

I am sure there are more classifications that can be done that way

LikeLike

I appreciate the thought, but that approach veers away from my purpose. I’m not trying to build a master model of every supergroup for every imaginable independent variable. I’m thinking in terms of provoking inspiration – a heuristic device rather than a complete one.

The idea is, given a few comparisons among a number of groups which, for lack of a better word, “work,” people or a group of people can better understand how to bring their inspirations into something that works too. It might be due to conforming to something they see there, especially now that they see at least something that’s operating upon it for story potential, or it might be due to averting from or even defying what they see.

For that purpose, the most useful principle is accuracy, specifically in its difference from either “complete” or “precise.” Those would work against the purpose. I actually want to avoid being either complete or precise, in favor of a few things which are provocative and not wrong.

You brought up another point which I may have to devote a post to – reducing the importance of “power level” in our discussion of comics superheroes. It’s right up there with the fascination/aversion regarding killing as a major distraction.

LikeLike

“teens, shared-origin, but not feared and distrusted.”, Jack Kirby’s Forever People?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes!

LikeLike

This is cool. I have been thinking though about the Champions Now playtests you shared videos of on adept play and how few seem to drop into these circles. Clearly with the Defiants we struggled in play with getting to the point of being a team, so maybe that’s why. But I’m then looking back and wondering if many of these categories would have helped out with the actual problems we had.

I’ve been thinking that these were at one end, finding a reason to come together and, more importantly, to care about each other’s problems, and at the other what I’m provisionally defining as “what does winning look like”. So for example for the Defiants just hitting bad guys wasn’t going to solve the characters problems and we struggled for a while trying to identify what would and then bring suitable solutions to bear.

However, when I try to envisage using the Venn categories you present to try and help resolve these I’m coming up a bit empty.

LikeLike

I’ve been musing over whether this or a similar diagram is useful for the Champions Now rules or not. On the one hand it does identify a few core punchy features of historical supergroups. On the other it’s limited in the very same way, i.e. historically, so that I’m risking imitation in place of inspiration.

In the altered version I currently have on my drive, which now includes an overlap between “government” and “common origin” and which has also added (God help me) several of the Wildstorm groups, it’s pretty clear that the two most deeply-nested/not-alike groups are the Fantastic Four (family, rock-solid membership with only minor wiggles, common origin) and the Suicide Squad (utterly institutional and dysfunctional at that, involuntary conscription, large and changing membership). So despite many overlaps and not much “shape” to the overall structure, there is at least some notion of ur-concepts or compatible combinations; you can’t quite pull the elements from a bag and throw them together.

Group identity vs. group goal is a subtle but important distinction. There really isn’t a “group goal” for most of these – they have goals of the moment and threats of the moment, mostly. What matters is their identity, which provides an anchor for goals and threats.

Taking that to the groups I’ve seen in play so far, I think the primary issue was for the players to agree at the outset that their characters were a group at all. I did not press it hard enough in many of my playtests, so that players went automatically from “I make up my guy and you make up yours” to “gee, how do we meet” as an in-play event. There’s a soft moment in between when yes, you have individual heroes, and now, we consider them a team, before play. The trouble is that I do not want that moment to devolve into conferencing, workshopping, world-building, play-before-play, and general over-programmed bullshit.

LikeLike

Here are a couple of more general thoughts, again, based on your accurate observation that the playtesting groups don’t fit well to the historical categories. That also seems to be the case for my Champions and role-playing superhero groups in general.

1. The Avengers and the Justice League (including its precursor the Justice Society) basically have “no reason to live.” Their nominal government association is totally hand-waved, and in the JSA/JLA case, symbolically flag-waved, until that topic became more interesting to the readership in the 1980s, specifically as a source of conflict. Until then, they’re together because they’re together, and that’s it. Their actual government roles and work are bluntly absent from any plots or problems.

2. The Teen Titans and the Defenders are the same but even more so, with even their in-fiction justifications acknowledged as absurd. The original for the former is like the JLA, “hey, we’re in the same comic,” and the reboot for the group’s most famous incarnation in 1981 is basically a rehearsal for the upcoming Crisis and makes so little sense it’s like a parody. The latter is full of dialogue explaining that they had no goal or purpose.

3. The Fantastic Four were not especially proactive except for one thing: Reed’s ongoing and often quite problematic research. Otherwise, their conflicts arrived through “remarkable coincidence,” e.g. the Moleman coming up through that particular city, Galactus landing on top of the Baxter Building; or from entirely emotional and internal strife, especially concerning the “other man,” Namor, and as developed later, Reed and Victor von Doom.

4. The X-Men, in both major incarnations, were nominally defined as “doing good in the face of prejudice,” but their actual plots dipped into this very rarely, and they were typically written more like the FF, with internal tear-ups and problems dropping from the sky.

In all cases, the stories seem to be based more on “weirdness magnet” logic rather than on proactive character goals.

Anyway, all this leads me to think that justifying the group’s existence is a very low priority for some of the most famous and loved and archetypal groups, and that to bring in such justification is much more conceptually tricky than one might think. Many of the groups in the diagram that do have such justifications are almost like refinements or commentary or deconstructions of the ones that don’t.

LikeLike

On the one hand it feels like it should be functional in play to just say: you’re super heroes, you’re in a super team, we aren’t paying more attention to why than the writers would in a comic. But on the other hand this probably reduces the possibility of interesting emergent features like The Defiants actually being this network of activists, with Brian, Michael and Finn being the super powered wing. Also in the play context of socially / politically relevant conflict is there a need for The Team to have more ideological heft so as to act as an opposing pole to Villains with potentially sympathetic, or at least understandable, perspectives?

I also wonder if there is a bit of a contradiction in the game between the clear incentive to work as a team to address problems – as the Defiants learnt to their cost when they split the party – and the way disadvantages for example mostly apply pressure to individual characters. My feeling is that the Champions Now character creation – the two statements and the three corners – probably goes a long way towards addressing the caring about each others problems side, but I feel perhaps that pressure to act as a team skewed which problems the Defiants then tried to deal with when.

LikeLike

I am clearly deranged or perhaps merely doddering, to have continued, and to have made this:

And then this, putting any and all Champions groups I played in or ran, ever, not including very minor game events:

I think there’s a couple possible insights. 1. The first diagram’s structure is not intrinsic, e.g., you can slide circles around. 2. Conversely, the first diagram’s structure is surprisingly robust, in that the sliding-around I did for the role-playing groups was quite minor, with only one slight relabeling to emphasize young-adult rather than strictly teens. 3. I didn’t have to invent any new categories.

I think this might actually address some of your questions. First, that “gee we’re just a team” is iconic for the JLA/Avengers but nearly always addressed more concretely for anyone else, at the very least in a meta-commentary sense (Defenders, Hero Alliance). And in the iconic case, we’re talking about egregious IP protection as the primary driving force, which means we don’t have to worry about explaining or including it.

Second, that all the playtesting groups and in fact any group I ever made/did with the game did find a home. I was a little surprised at Legacy given that the shared origin was emergent rather than established at the outset, but it’s no less solid thereby.

LikeLike

Sorry I missed this post earlier.

My interest here is purely from a game design POV. As RPGs work best (in my opinion) as cooperative group efforts, I decided a while back that any “supers” type game needed to have a team focus right from the outset…though I suppose “team” could be pretty broadly defined (“we are the individual protectors of New York” or even “of the Earth!”). However, I often got bogged down in the actual refinement of the concept for the multitude of different team examples available.

Seeing these diagrams is helpful. However, as I look through them, I feel like the teams that are most “beloved” (which I define as being “most compelling” and/or having the most “staying power”) are those that do have familial ties…even surrogate familial ties (Dr. X is a parent to his X-children who share sibling relationships…if not romantic ones). This isn’t any huge surprise, I suppose (long-term group dynamics tend to take the form of family dynamics over time), but I can see clearly where certain teams/titles didn’t “work” for me because they lacked these familial relationships…when they didn’t develop (and develop right quick) I burned out a lot quicker on a title.

For example, I’ve read Avengers off-and-on over the years. The most compelling stories (for me) were the ones that dealt with the Pyms and their various issues (whether you’re talking their marital issues or the relationship with recurring “mistakes” like Ultron). I think The Ultimates “reboot” of the Avengers did a great job of putting the relationships between the team members front-and-center…how DO these semi-functional (socially) super-beings interact with each other? That is far more interesting than what they’re doing to various “epic level threats” that arise. Yes, I want to see them kick some ass, but once the relationships start drying up, I stop tuning out (and stop buying the comics).

In an RPG, you want to make the game compelling for the folks at the table, so that THEY keep coming back…and I don’t think it’s enough to just provide tools for creating a “deep” or “rich” character. How many flaws, psych issues, or NPC dependents my character has isn’t nearly as interesting (over time and multiple sessions) as my character’s relationship with the other (real) players at the table. In the old MSH RPG I always hated having to do random tasks for NPCs just to keep from losing karma points (“Who cares if I’m supposed to have lunch with Aunt May?!”); doing trivial shit for NPCs…even having to save them from villains!…is seldom as interesting as what’s going on with my fellow team members (whether in a fight/system situation or a social interaction).

[and if the NPCs ARE more interesting than your fellow PCs, that may be a sign something’s wrong]

I know there are some games that have put the relationship between characters front-and-center to their game play (I’ll have to dig out my copy of Hillmen and read through it again), but as I remember, they tend to give equal weight to ALL relationships, PC and NPC alike (which might have something to do with why I’ve let those games slip through the cracks over the years…). In a supers game where, presumably, all the players are heroes I think the emphasis needs to be squarely on the group dynamic of the team members. Origins, governmental control, marginalization by the public, reason for existing…all those things are secondary considerations; fodder for adventures at best, and mostly background “color.” The “meat” is the relationship between the team members.

At least, if you want the game to be more than a mini-series.

Anyway, that’s what I got out of this post…and thank you for that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi JB! I agree about the team focus; that’s more or less a given with Champions. I’ve been surprised in my re-readings that it’s not addressed at all in any of the early supers RPGs. If I’m to go by my own views and perspectives from that time, I think that the authors and users of these books were so well-oriented toward the source material that we didn’t have any problem “just knowing” that superheroes made teams and that team titles were what we wanted to do. This was the heyday of the New X-Men and the New Teen Titans, and I might even blasphemously claim that the fanbase had a better grasp of the working aesthetic in them and in the wave of new groups than their creators did.

I am a little cautious about “quasi-familial ties” as a guiding term. It corresponds to any kind of emotional resonance at all, becoming, “teams where members get emotional.” Not only is that very general, it also seems to me more like a result than a grounding feature. So that your preference for these groups isn’t a preference for a kind of group, but fora comic which has relevant and resonant writing. I’m sympathetic to that point for sure, but it’s not a useful device for thinking about how to inspire people to arrive at a superhero group concept they’ll enjoy.

I think the question is less about what kind of team we are, then whether we can use the superhero team platform to arrive at powerful relationship play. Then the question I’ve poked at in this blog post is a subset – whether the fictional team definition or grounding concepts is useful for that.

The answer is oddly mangled in the actual superhero texts, and to get off-track from my answer to you for a moment, I suggest that we get far, far away from the invisible assumption that if a superhero group title is “big” in industry and fandom terms, that’s an indicator of its quality or resonance or doing-it-right, i.e., proof of concept. The JLA and the Avengers are big in that sense because the two companies kept publishing the fucking things, mainly to keep dozens and hundreds of IP in hand. That some few creators took the opportunity sometimes to get some good writing in there is all to the good, for me and you as comics-buying kids, but it’s not because of some group concept in the fiction.

And giving the group some grounding of that kind is no guarantee. Setting aside for the moment the many titles which “make sense” only because they reference the JLA and Avengers, some of the pretty solid why-we’re-together concepts made for incredibly bad stories. Even villain-of-the-week is better than another spate of misunderstandings and operatic but unsympathetic bad decisions, which are all over the titles in the diagram.

And I don’t think those two things have a simple either-or trade-off either. If relationships and problem-of-the-week are zero-sum way, then yes, the former obviously wins. And there are plenty of comics which fell into that problem, whether for the occasional issue or constantly. But I submit two ideas for you that are perhaps more complicated.

First, that relationships cut all kinds of ways, so those with adversaries may be at least as compelling as those with teammates. In other words, the relationship is good reading or it isn’t, regardless of with whom, and that again, it’s not either-or – my relationship with my villainous dad adds nuances, problems, or solutions regarding my coming-of-age romance with you, my awkward but loveable teammate. (Geez, how many comics titles and famous arcs did I just reference with that? Twenty?)

My second idea, speaking as someone who has some claim to promoting relationship mechanics in RPGs, is that no mechanic “does” things in the sense of making things happen or fun, like a gear or pleasure-button. If treated that way, the best thing it can do is fail inconsistently to keep the user uncertain and thus more easily addicted. Instead, I want to reverse your phrasing:

I will take issue with you there, because I think the game cannot and will never be compelling as stated that way. What it can be is inspiring via its properties and useful in its operation, and re-inspiring to cycle/spiral into new use – again, always, going to my analogy with musical instruments.

My application of that point is that I’m not sold on the distinction between player-character relationships vs. PC-NPC relationships. If I may be rude, I suggest that your observation that NPC relationships were boring is a matter of playing boring and irrelevant NPCs.

Let’s take that to relationships as explicit mechanics, something I’ve been going into with several videos at Adept Play lately. I’ve been trying to convey the idea, over and over and from different angles, that you can get X by nuancing Y enough so that X is very easy to develop, or vice versa. In other words, whatever you have explicit mechanics about needs to be assessed for the reliable results that are not explicit, and in practice, are still mechanics thereby.

So if you have relationship mechanics among PCs, we should be looking for plot phenomena emerging that are spiced and sparked by them, whether whoever it is we’re fighting or relationships among many NPCs. And vice versa, if we have relationship mechanics to the NPCs, then we should be looking for plot phenomena emerging that are spiced and sparked by them, specifically, relationships among our PCs.

Either one works! It’s not the case that one is more intimate or more relationship-y or more compelling than the other; the quality of the design is a matter of implementation, not picking the Good micro-mechanics over the Bad. We have a lot of bad design and bad experiences that lead us into such judgments, unfortunately and perhaps you know as well as I do the people who would scream in rage at your call for PC relationship mechanics and swear up and down that explicit relationship mechanics are “sterile” and “artificial” and “ruin the game.”

Your observation that PC+NPC relationships, i.e, relationship mechanics with anyone and everyone all the time, seems uncompelling is very important. One may ask after all, “why not both then? Wouldn’t that be perfect?” The answer is not yes, although not no exactly, but definitely not yes. But again, I don’t think it’s because NPCs have been included, I think that those designs have historically tended to crowd out emergent plot effects in favor of locking them all down too much.

Whew! Back to this part of the text writing, I think. You’ve helped me a lot with that.

LikeLike

Thanks for taking the time to write a thoughtful reply. I probably didn’t communicate as clearly as I needed: I wasn’t talking about writing a game purely based on relationships (though that might be interesting…) and certainly not relationships limited to familial (or quasi-familial) ties. And I understand the industry’s pushing of teams for IP reasons (never did much like JLA) and the pitfall of judging “quality” by “longevity.”

Any mechanics for relationships that I design would probably be on the “light” side regardless…I’m just thinking they need to be present in some regard. A way that encourages players to interact with each other…perhaps tied to the reward system. How that interaction occurs may or may not be “quasi-familial” or “non-action-y.” It’s just something I’m thinking about.

And for what it’s worth, I don’t think you’re rude to suggest our NPCs were boring…that’s certainly possible! Just not sure there’s a way to facilitate the creation of super-interesting or compelling NPCs. I guess, I just think it would be easier to facilitate PC interaction because players (I’d hope!) have more potential “depth” than imaginary people. I’m lazy that way.

; )

You’ve given me a lot to chew on, Ron. Thanks again and please keep at it. I was just checking out your Champions Now playtest doc. I look forward to seeing the publication of your Super-related projects.

LikeLike

Feel free to contact me by email if you want a closer look at the real/done work. It seems to me that demonstrating how the rules really grab the topics you’re bringing up, perhaps in a recorded video conversation to address them, would be valuable to a lot of people who are following or backing this project.

LikeLike

What about having INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS as a Disadvantage category? Players could work out shared Disadvantages between themselves and then both put the same Disadvantage on their characters. They don’t have to be romantic either. Perhaps Miasma is being watched by a team mate who doesn’t believe her change to the side of the angels?

Are you familiar with the subplot mechanic from the original DC Heroes? Players work out a subplot, like an on-going mini-adventure or side-trek, write it out and give it to the GM to run and then they gain experience when it appears and they actively engage with it. No experience is gained just for taking a subplot, only for engaging with it when it appears. Two players could formulate the same subplot between themselves and the provide it to the GM to facilitate. (It also takes some of the pressure of the GM in providing compelling stories; theoretically, if it is a player supplied subplot, they will be emotionally engaged in playing through it).

I know you are not a fan of a lot of negotiation and pre-planning prior to playing but the players can sort out the shared Disadvantage or the subplot between themselves before play.

LikeLike

It’s a little tricky to see which of your points are for discussion, and I don’t think any of them are question, so this reply about the relationships is more of a guess. Let me know if it qualifies as a reply.

You’re right to anticipate my thinking that a front-loaded inter-player-hero relationship carries some risks. They mainly concern blowing smoke, i.e., cheap histrionics, “it says I resent you so I act resentful,” because they are neither validated by events nor overturned by decisions under stress.

I am calling it a “risk,” not a “problem,” so please don’t perceive this as full disapproval or disallowance. In fact, it’s totally eligible in the rules as I have them now.

* Players can choose whatever Psychological Situations they want; nothing forbids an emotion or attitude about another hero. Play presupposes that the “team” already exists so it’s not like they have to make up some extra reason why they know each other.

* The systems of change for the hero sheet include more explicit means of altering the Situations than the original game had for altering Disadvantages. You can shift them around without having to spend points. So if a player’s hero started with no relationships like those you’re describing, they could become Situations if the player wants them to.

I think those two details of the rules add up to a “yes” for your point. It also allows for perfectly understandable backstories when you want them, like a husband-and-wife team or just as you describe for Miasma, “I fought her as a menace, whaddaya mean she’s on the team.”

However, since the risks are real (i.e. I’ve seen the problem in play), I am not designating the idea as a special sort of Situation or bringing it forward in the text as a best-practices option.

Let me know if that made any sense.

Oh yeah – I do know the Subplot from DC Heroes, having played the game and (with the players) gravitated toward those rules. My revision of the DNPC rules is strongly influenced by them, as well as my rules or discussion for conducting play in the moment.

LikeLike

Thank you for the reply. You are right, they were not questions, just suggestions. I do understand what you mean about defined Disadvantages locking players into or allowing the justification of disruptive behaviour.

As for the subplots, it’s nice to see the now ancient mechanics still getting some love!

Is there a newer play-test document than July 2018, by the way?

LikeLike

“Play-test document” is not too applicable a term any more, since we’re now looking at submitted text that’s going to undergo a final hard look for content and style.

As a related point, everything from last July until this point has been steadily mutated, altered practically weekly through my and others’ use of it in play.

If you want to learn more about the current, just-about-final form, we should talk about it directly. I think it would make more sense to you that way, and if we make a video of a conversation, it would be very helpful to other backers. Send me an email if you’re interested.

LikeLike

Pingback: Doctor Venn’s circle strike | i can bend minds with my spoon