A fearful symmetry is born

Posted by Ron Edwards

Now it’s time to check out Intruder as he might be expressed across the comics/games/games/comics via licensing.

Now it’s time to check out Intruder as he might be expressed across the comics/games/games/comics via licensing.

This is the eighth post about the villain protagonist (anti-villain, whatever) Intruder, created by Scott LeMien and me, including a fun comics story. The previous posts include Intruder alert, “I Am I” (this is where you can read the comic), Forms and features, Rough and ready, Oh noes, What medium and idiom hath wrought, and In the Eighties.

You can see the new comics/game crossover explode into existence in the mid-80s. It’s obviously there for the two big-company licensees, but it’s also more subtly present for the games discussed in the previous post: the Heroes Unlimited supplement featuring the Justice Machine (1984), which was associated with the early version of the comic (several publishers); the launch of the Champions comic (initially Eclipse Comics, 1986) by Dennis Mallonee using the original Champions authors’ characters (see Recursion isn’t just a river in Egypt); the limited series for Villains & Vigilantes (Eclipse Comics, 1986); and the interrelationship between Wild Cards and GURPS: Supers, itself to be expressed in comics later (Epic Comics, 1990; see So not making friends here). The concept also applies at least in terms of reader perception and enjoyment for Bill Willingham’s scenarios Death-Duel with the Destroyers and The Island of Doctor Apocalypse for V&V (both 1982), as revised into the comics title Elementals (Comico, 1984; see Elementary); and for the origins of the Wild Cards series in playing Superworld.

I’m not concerned here with the nuts and bolts of IP and licensing, but rather with the hobby embrace of “do the comics with the game” and “do the game with the comics.” This is different from the games I discussed in the last few posts, which did this:

- Looking back to the comics as shared inspiration, with game authors and game users conceived as we-are-players-one-and-all.

- Looking ahead to play as its own unique creation with no ongoing relationship to specific published comics.

Instead, now here’s a whole new commercial relationship: “buy the comics because you play the game” + “buy the game because you read the comics.” By the mid-1980s, notions of customer loyalty and buying into your promised fun, sequentially and long-term, had finally become the social standard for Marvel and DC comics and was desperately sought both by new comics companies and game companies.

Now pay attention to this huge related point: this is also the birth moment of official and editorial ‘Verse for both companies. Look at those Universe/Who’s Who comics titles, each bought sequentially and each to be revised periodically so you could buy them all over again. Buying the endless supplements of “these characters built in game terms” is the role-playing hobby mirror.

One of my friends devoted a fair piece of time he should have spent studying to converting every single character in the Official Handbook to Champions 2nd edition, starting with the bench press weight and proceeding through every detail. He completed it A to Z, and I’m betting he wasn’t alone. I want you to think about why! He was very proud that his intended gaming materials, unlike those of mere others with less commitment, were properly official – or in later pop culture terms, canonical. Consider his sense of accomplishment, capture, mastery, codification, and sense that now we can finally “really” play. Examine whether you get that, and what kind of slavishness to commerce is required to get it, and to be happy about it.

The happiness is only comprehensible within an entirely new concept of hobby participation. Role-playing superhero comics is now conceived as representation rather than creation. Superhero comics fandom is now conceived as consumption of received goods rather than participation. Put these into the larger matrix of the hard push of comics into film, the tight telescoping of distribution for both comics and games, the speculated financial value of the physical comics, and the newly-minted narrative of comics’ history as “progress” or “maturation.” Bits and pieces of these things had always existed in comics and gaming, but this moment is exactly when they took on hideous cultural life.

Fortunately, there is good news: that beyond any reasonable expectation, the licensee superhero role-playing efforts for Marvel and DC have yielded some remarkably good games.

There are four Marvel-based role-playing games, examined in some detail in my Monday Lab seminar Make Mine Marvel. That discussion reveals the understandable, but nevertheless unexpected effect that each game beautifully captured the Marvel-ness of the characters from the decade prior to the game’s publication, better than the company’s contemporary comics were doing.

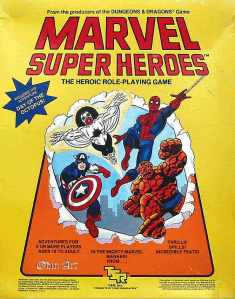

The first one, Marvel Super Heroes (1984) is the only RPG, historically, to be completely upfront about playing villains, even a villain group. It’s not even presented as a dedicated, self-aware option but simply through specific rules sitting right there in their relevant sections and a very casual reference to doing so, as if “anyone would do it” and “everyone knows that.” I point with great pleasure at the Karma rules for villains – they lose twice as much for failing to interact with loved ones and close friends. This puts a lot of teeth into Intruder’s relationships, as initiated by Scott and brought forward in our comic. (see my previous post The little game that could about this game)

The first one, Marvel Super Heroes (1984) is the only RPG, historically, to be completely upfront about playing villains, even a villain group. It’s not even presented as a dedicated, self-aware option but simply through specific rules sitting right there in their relevant sections and a very casual reference to doing so, as if “anyone would do it” and “everyone knows that.” I point with great pleasure at the Karma rules for villains – they lose twice as much for failing to interact with loved ones and close friends. This puts a lot of teeth into Intruder’s relationships, as initiated by Scott and brought forward in our comic. (see my previous post The little game that could about this game)

One of my very few criticisms of the design is that mentally-oriented characters are not well built and played in terms of how Reason, Intuition, and Psyche interrelate; Psyche, especially, is shorted as a mechanic. I frankly can’t make Intruder “straight up,” as it were. However, the rules include an outstanding subroutine for magic – perhaps the best single magic system in the hobby. I’d use it for the AI, which for this game makes most sense to be treated as a separate character, also as a villain, with its own Karma. Then their physical integration in the story becomes a matter of plain role-playing and conflict between them can be played as ordinary interactions.

Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game (1998). Although the rules assume you’ll be playing a pre-made version of a character, it also includes rules to adapt or construct a character from a comics story, which is what we’re doing here. It’s kind of neat to see rules specifically made for doing that.

Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game (1998). Although the rules assume you’ll be playing a pre-made version of a character, it also includes rules to adapt or construct a character from a comics story, which is what we’re doing here. It’s kind of neat to see rules specifically made for doing that.

It’s also built for trenchant confrontation, especially when motivations are involved, i.e., fights seem to be less about crimes and more about who gets to prove they’re right … and mechanically, a villain may conceivably triumph. The mechanics include the accumulation of Doom Bank cards for the GM, which spikes villain effectiveness unpredictably per confrontation, so you never know whether this particular instance will get your heroic ass kicked. I’ve wanted to play it for a long time, especially to see how these emergent system features fit with some of the planned/programmed phrasing in the preparation and play sections.

So, working through Intruder, after slogging through the completist skill philosophy in Champions 4th and GURPS: Supers, it’s a relief to see meaningful parsing detail in this game’s skills and powers. It’s easy to express strong differences in personality and style for basic functions like “in charge” or “tough” or “sneaky.” For example, Leadership, Empathy, Mesmerism, and Hypnosis work very well for Intruder, and not the listed Mind Control power, which is reserved for puppeteer-style actions only.

The same point applies to its options for Hindrances and Calling; this is the first structural system I’ve found for which Intruder’s motivations are not (i) provided whole cloth by the player or (ii) a difficult edge case among the options. Instead, they may be expressed in a variety of equally interesting ways depending on one’s views toward his morality and toward the influence/servitude of the AI:. I think his case breaks down into these possibilities:

- Calling: Uncontrolled, Hindrance: Hateful

- Calling: World Domination (which he thinks is Idealist), Hindrance: Transformative, and with or without Hateful as a second Hindrance

Marvel Universe (2003) is an unappreciated game whose primary system feature is not widely understood. We talked about it in the Monday Lab linked above, but briefly, when you lay out all your little stones to indicate your character’s effort toward the current situation, it’s hidden from everyone else, and that goes for everyone. So you don’t find out the order of action and the effects of actions until the big common reveal. It’s not a bidding war system. It also features an unusual character development and improvement system based on what the player decides what was most significant for the character’s saga, each session.

Marvel Universe (2003) is an unappreciated game whose primary system feature is not widely understood. We talked about it in the Monday Lab linked above, but briefly, when you lay out all your little stones to indicate your character’s effort toward the current situation, it’s hidden from everyone else, and that goes for everyone. So you don’t find out the order of action and the effects of actions until the big common reveal. It’s not a bidding war system. It also features an unusual character development and improvement system based on what the player decides what was most significant for the character’s saga, each session.

I haven’t played it, unfortunately, so this is a potentially naive statement, that villainy as such looks a bit under-developed compared to the other Marvel games. However, that development system does catch my eye as a mechanism to discover and continue important relationships and backstory components; you could in fact begin not knowing at all who the Green Goblin is, and it could get worked out through this particular family of mechanics over several sessions. The game is built to develop – only through play – an organic multi-character tapestry of consequences, desires, evolving disadvantages, and revelations, which includes the villains as well as the heroes. It strongly influenced the methods I playtested and applied for the second word in the title of Champions Now.

No Mind Control is listed at all, which is weird and interesting, considering how central this effect is to the canon, and I think this has to have been a deliberate decision. Therefore, similarly to Marvel Super Heroes, I have to triangulate other rules to “get there,” and the best route would be the magic system. However, in this case, I’m keeping the AI as a ‘gestalt’ effect across the sheet rather than an autonomous entity.

Critically, with or without the magic version of the AI, Intruder is only playable if “doing things” matters outside of combat. Similar to GURPS: Supers, if play is only about “how we get to the planned fight,” then all this effort and specification is a complete waste of time. But if what the fight even is, where it is, why it happens and what might happen are left to play itself, and are subject to the outcomes of rolls and interactions, then the game has plenty of methods to serve.

Marvel Heroic Roleplaying (2010) is built partly by kitbashing a bunch of games developed at the Forge, including but not limited to The Shadow of Yesterday and Dogs in the Vineyard. Play is organized by Events, and the rules for villains are embedded in those. So it’s not just “build a character,” because you have to have an Event in mind. I’ll consider it to happen after the three-part sequence in the Supervillain You section. So, he’s written as antagonist, in the red format, and nicely suited to “troubled Captain America” or to the Avengers in one of their anti-authoritarian phases. (Reversing it entirely, so that a non-GM player could use a “red” sheet, is intriguing but not easy to implement.)

Marvel Heroic Roleplaying (2010) is built partly by kitbashing a bunch of games developed at the Forge, including but not limited to The Shadow of Yesterday and Dogs in the Vineyard. Play is organized by Events, and the rules for villains are embedded in those. So it’s not just “build a character,” because you have to have an Event in mind. I’ll consider it to happen after the three-part sequence in the Supervillain You section. So, he’s written as antagonist, in the red format, and nicely suited to “troubled Captain America” or to the Avengers in one of their anti-authoritarian phases. (Reversing it entirely, so that a non-GM player could use a “red” sheet, is intriguing but not easy to implement.)

Intruder is easy to make for this game because of its Event-driven structure. Figure the Event itself is a specific subornment or destruction of a given institution, “changing society,” relying on taking over a specific person

- So, each Milestone is easy: it’s basically success/failure of the necessary steps of what the villains are doing, and they’re often associated with big scene shifts.

- The real gold is found in the Unlockables, which (once you take a look at what I’ve listed) provide all sorts of intersection with the game’s strong “meltdown” mechanics. (In this game heroes are always grabbing their temples, screaming “Nooooo!!”, and hitting each other.)

- Add to that this game’s version of the escalating Doom during villain confrontation (similar to the 1998 game but with dice), and you have plenty of what Intruder is built to do, especially since it cannot be planned or expected before play.

So here, villainy is again highly valued by the design: unless you know what they want, why they’re there, some things which might happen (any which way), and basically the whole “why” of the villainy, then there’s nothing to play. All four Marvel games shine best when this exact feature is placed at the heart of the experience.

However, perhaps counter-intuitively, I’m struggling a little to see how play deviates from the prompts and the prepared opportunities for drama – is such deviation (“organic,” “emergent”) even possible, or are players there to experienced what’s planned for them?

That also applies across Events as well as within them. My personal hope is that the game fuels sequential drama, in that whatever happened last time affects how you’re going to build the hero this time, i..e., that however the heroes interacted and responded in the prior Events sets up how they’re built and played in the next one. I’ll have to play it for a while to get a better handle on that, but that’s what I’ve assumed or hoped in setting up Intruder the way I did.

As for the specifics of what he can do, the game uses a “designed for this time” model (which was also the case in the original version of With Great Power …, see Scratch Pad), meaning that characters are built specifically for preparation, out of an amorphous and unconstructed list or page of notes. In other words, you “build” the things that matter for this particular appearance, not as a full portrait of everything the character is. Therefore the Distinctions that you’re seeing here could easily be different, if I wanted to focus on, say, his family past and to maintain the cancer only as a colorful detail. Furthermore, since there’s no explicit currency, you just pile stuff into the Power Sets as the concept demands, including the spot-rules called SFX.

I’ve written about DC Heroes (1986) before, in Getting it just right, to acknowledge its all-hobby superiority in designing the universal resolution system, and also, in that very successful, to be careful what you wish for.

I’ve written about DC Heroes (1986) before, in Getting it just right, to acknowledge its all-hobby superiority in designing the universal resolution system, and also, in that very successful, to be careful what you wish for.

Here I’m more interested in thematics, for which the game is definitely not universal, because Intruder presents a telling mismatch with the game’s entire notion of villainy. The game was clearly written looking back upon DC history as distilled into the first couple of years of the New Teen Titans, rather than what DC was at that moment becoming (as an indicator, there’s some very tortuous text about the just-beginning Crisis). So villains are rogues’ gallery crooks who do crimes, and heroes are there to stop them, usually just in time. Anything like “Well-Intentioned Extremist” is notably lacking from the listed Villain Motivations, and anything like his actions or intentions is absent from their random encounter/preparation method. You don’t have to use the latter method, and I suppose you can simply inject the content I’m talking about yourself, but textually, you cannot get contingent morality and intersecting drama, as opposed to the caper of the next episode.

Intruder is pretty solid in terms of portraiture. The Skills were the hardest, aside from Charisma, because most of what he’s got is found in small sub-categories across many different Skills, without the general categories themselves. Unsurprisingly and lots of fun, the Subplots are gold, especially Power Complications.

Play might be a different story. As I mentioned in the linked post, effectiveness in this game isn’t really the magnitude of the points and dice, but rather the Hero Points in play at any given moment. Their purpose is explicit – for the heroes to get stymied at first but then to turn the tables. The pacing of the problem-obstacle-effort-overcome arc is practically tuned to the minute based on the starting ratio of Hero Points between heroes and villains. You can see that the creators’/franchise’s designated Fave Villains, like Deathstroke, are basically overloaded with enough Hero Points to “get away” as needed. That’s an interesting call to make regarding Intruder: is he front-loaded with mega-villain-getaway status or not?

A few other licensed games are around, most of them clearly influenced by Champions to the point that I think the creators must have been using it for a long time before shifting to their own publication plans.

Superbabes (1993) is associated with the extensive line of Femforce comics (see here if you’re not familiar with them; whatever one may judge or say, they have been a significant player in comics publishing for quite a while, and are still going strong). One of its major features is extending your actions past the listed things on your sheet, which incurs a later risk of having babe-o-licious things happen to you.

Superbabes (1993) is associated with the extensive line of Femforce comics (see here if you’re not familiar with them; whatever one may judge or say, they have been a significant player in comics publishing for quite a while, and are still going strong). One of its major features is extending your actions past the listed things on your sheet, which incurs a later risk of having babe-o-licious things happen to you.

Obviously, the parameters for content are highly specific, and Intruder cannot possibly be a player-character, but he could be a pretty interesting antagonist, especially given the shifting and often problematic relationships the heroes have with governments and corporations. I say “could,” however, because the game lacks almost all mention of super-villainy, which notable because its presentation of aliens, agents, and anything else is complete and even careful. … With the secondary weird exception that it does include the explicit option of playing “all villainnesses.” This kind of thing is always my tip-off that the designers knew so intuitively what to do with villains (for their game, for this concept) that it never occurred to them to describe it instructively.

Given the point system, he has to be built pretty “big,” much as a really effective version would be in GURPS: Supers or Champions 4th edition. However, not as big as I first thought; putting him at 3rd level works fine, and seems reasonable for a solid antagonist to introduce. I could even have tweaked the magical and “realm” rules as I did for a couple of other games, but as far as I can tell, that’s very dimensional and magical in this setting and not very “cyber,” so I didn’t.

This system gives me the opportunity to point out that telepathy is very different from game to game, so that here, it makes sense to include the relatively minor Read Minds as an adjunct to the Persuasion skill, whereas in other games for which it’s more Professor X style, it wouldn’t. You can define things a bit subtly across the rules-options too, so that I’d use the Hit’Em Harder power, defined as energy, as part of the “stealing Gizmos” subroutine of the Gizmo rules.

Heroes & Heroines (1993) is an unusual beast: it’s written explicitly as a generic system seeking licensing partners, which for purposes of this post, is almost too pure an ambition, as if I’d made it up. Apparently, the idea was that many comics companies would flock to this one gaming company to provide their licensed gaming needs. The influence of the Universe/Who’s Who model is explicitly present, as evidenced by calling Strength “Bench Press Weight.”

Heroes & Heroines (1993) is an unusual beast: it’s written explicitly as a generic system seeking licensing partners, which for purposes of this post, is almost too pure an ambition, as if I’d made it up. Apparently, the idea was that many comics companies would flock to this one gaming company to provide their licensed gaming needs. The influence of the Universe/Who’s Who model is explicitly present, as evidenced by calling Strength “Bench Press Weight.”

The only license it got was for The Maxx, which I’m sure was not precisely what the authors must have had in mind, and the game has not survived even as a hobby reference point, let alone as a played-and-known system. Upon looking it over, words like bland, nonsignificant, and pedestrian come to mind.

That’s why making up Intruder with it was a real shock: he’s surprisingly functional and clear, as “what he does” is perfectly available from the specifications within powers or particular points of overlap among different things. Also, as you can see from the sheet, the options and mechanics are straightforward and simple. He comes in at 418 points, which is less than the range recommended in the rules, and leads me to think I could really beef him up to be a worthy antagonist, whereas most of the other games forced me to struggle to “fit” him.

Is this a stealth good game? I think it might be! It may be capable of expressing a wide range of villainy and powers concepts that would be edge cases in most role-playing designs, or that would rely on abstract or “ask the GM” mechanics (e.g. the magic rules in two of the above games, for the former, and GURPS: Supers for the latter).

Uniquely among superhero RPGs, it features a combined random+points method for characteristics. By contrast, this is really common for fantasy games of the same period. Here, I think it’s similar to preventing card-counting, and leads to more discussion we can do in the comments if anyone’s interested.

I was looking forward to including Big Bang Comics, the game associated with the company of the same name, since it seemed almost a perfect recapitulation of the points made in the previous post and in this one, but it seems to have vanished completely even from its own publisher’s website.

I do have some conclusions. Like them as games or not, or however your critique may go in terms of comics and role-playing history, each of these really does take its own stand on two critical issues:

- What a villain is and how that relates to everything about play, “what we’re here for.”

- What Mind Control is and how it may be usefully played for fun.

Maybe the close association with texts forced this – the authors had to think about how it worked and what it did in these comics, i.e., not as a logical or engineering concept, and therefore ended up with functioning, non-generic rules design. Given each one’s response to the above bullet points, these games split into two understandable and even admirable categories: those which “arrive” at Intruder rather well, and those which flatly state “we don’t do that” and spare us half-assed or fake attempts.

Superhero role-playing is notoriously difficult to design for, and I am finally understanding why: you’re spinning two dials. One concerns the procedures and options for play, with whole subsets like morality and villainy, let alone powers as significant agency; and the other concerns the comics as an ongoing, dynamic, created process rather than an encyclopedic body of facts. You have to “hold one of them down,” I think, in order to arrive at the best ideas and inspirations for the other.

Against all expectations that licensed games would be the least interesting or ground-breaking, I think that locking the comics dial down a bit had exactly the opposite effect: some of most insightful designs in the history. The results even transcended the “terrible symmetry” that consumed and – yes, I’m saying it – ruined the comics themselves! Really, you and I ought to be playing all of these.

Posted on May 10, 2020, in Gnawing entrails, Supers role-playing and tagged DC Heroes RPG, Heroes & Heroines RPG, Intruder, Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game RPG, Marvel Super Heroes RPG, Marvel Universe RPG, Scott LeMien, Superbabes RPG. Bookmark the permalink. 11 Comments.

Speaking of liscenced games. I’m surprised that you didn’t try Intruder with Mutants and Masterminds DC Adventures.

LikeLike

I don’t make any claim to completism. I don’t have the game and can’t be troubled to hunt it down and process it, partly due to lack of interest. If I had to pick one game to do that for, it’d be Golden Adventures, the 1980s upgrade of Superhero 2044.

LikeLike

Feel free to write up your thoughts on how it might be done, and reflections on the results, and I’ll be happy to include it here!

LikeLike

I admit I am a noob to playing RPGs myself. and recently other outside pressures distract me for the foreseeable future. However since The Intruder is your project, I really hope you can consider Mutants & Masterminds (or their liscenced DC Adventures). Reviews from longtime hobbyists speak highly of those. You may be able to procure a copy of an out of print pdf from a site such as The-Eye.

LikeLike

Finally, some games that I’m familiar with! I’d like to engage with the thesis of this post, but first I have to be a geek.

MARVEL SUPER HEROES was published in 1984, but they did a deluxe edition in 1986. Some changes are especially relevant to Intruder.

Notably the power “Pheromones,” which basically means if your mojo is powerful enough, a person becomes your friend for a while, meaning that Popularity rolls become much easier. It seems to fit Intruder’s “nudge” form of mind control fairly well.

There’s also “Computer Links.” As someone put it, “Back in 1986, having WiFi was a super power.” It seems to fit the Intruder concept as well.

Interestingly, Mind Control in the 1986 version of the rules is treated as a crime. Super heroes lose 10 Karma, possibly more, just for using it. (It’s implied, but not stated, that a villain would gain Karma.)

MARVEL HEROIC is morally agnostic: you could absolutely run Intruder as a player-controlled villain.

Interestingly, Mind Control in MHR looks different than it does in SAGA or MSH. In those earlier games, Mind Control is a toggle: it’s total, until it’s not. In Marvel Heroic, Mind Control is more like a dragging effect, like the rollover penalties in Sorcerer. The control depends on context and is very far from total.

(I have read SAGA, and even made up some cards for it, but never got around to playing. I think MARVEL UNIVERSE added Mind Control in the errata as one of the options for Telepathy or something. That game needed an editor very badly.)

I ought to try to organize something sometime, with all this stay-at-home time.

LikeLike

I’m interested in the “engage with the thesis of this post” part, now that the useful footnotes are in place.

LikeLike

As far as whether these games are “fit for purpose” for playing a super villian protagonist, I’d agree that the three I mentioned above all would do the job fairly well; I’m not familiar with the others.

But as far as the weird corporate synergy between comics and gaming, I have an historical comment, a psychological comment, and then a mixture of both.

—–

Historically: as someone who was 10 in the mid-80’s, none of what you’re describing as “official” ‘Verse registered or stuck. None of my friends took the Official Handbook stuff as anything other than, “Here’s six billion characters you’ve never heard of before, and here’s the deal with each of them.” Likewise the published gaming stats were pretty obviously some flunky’s half-assed implementation. We never once played in the Real Marvel Universe, and the notion that this would be of any particular interest would have seemed extremely alien to us.

I remember a conversation I had once about the MARVEL SUPERS game. Scott, who would have been around 15 at the time, was telling me how he and his friends laughed that Hank Pym only had an “Excellent” intelligence score, which for a super scientist in that game is pretty pathetic. Scott also apparently enjoyed playing the Punisher, shooting people in the head, and collecting their villain gear.

So I think there’s a perfectly ordinary gradation between young adults, teenagers, and little kids as far as how this stuff was perceived.

—–

Psychologically: as an adult, I can definitely enjoy “a good [CHARACTER X] ” game–or dread a bad one.

One of my very favorite gaming experiences was in 2009, playing “With Great Power…” to do a Silver Age riff on Spider-Man and the Thing teaming up. The players and I loved the hell out of these characters, loved this particular era of comics. We ended up with a really fun set of sessions, and one piece of that was that this was “a good Thing story” and also “a good Spidey story.”

Buoyed on that experience, I ran “WGP” at a local con using some DC characters just as a way to get immediate buy-in from people who maybe didn’t know comics. The guy playing Batman decided, basically, “The hell with Alfred, I don’t care if General Zod vaporizes him.” I ran with it–RIP Alfred!–but it was jarring. I came away with thinking, “This wasn’t a great Batman story.”

Not that the player did something out of bounds–dude, it should be AMAZING to see a situation where Batman would sacrifice Alfred! But in play it was a really off-the-cuff type of thing. I would have enjoyed that moment a lot more if it had been “Nocturnal Flying Rodent Man” instead of, y’know, Batman.

—–

Mixture:

Maybe the only fuctional “adventures” for the MARVEL SUPERS game was an extended riff on the “Days of Futures Past” storyline. I had one of these as a kid, and it baffled me–I was too young to realize that it was a campaign setting, a sort of meta-adventure. (There were 4 products in this series; only the first two are any good.)

We never played it as kids, but I’ve gotten some mileage out of it as an adult, and I think it works as well as it does *because* it’s licensed, and building off a classic X-Men story, published at a time when “Uncanny X-Men,” “The New Mutants,” and “X-Factor” were all taking a protracted look at the metaphorical Holocaust.

It’s a situation where if this had been, “Evil Robots Conquer America, Outlaw Superheroes,” nothing would change functionally. It would still be a good gaming prompt. But for fans of the original story, and fans of the mid-80’s foreshadowing (post-shadowing?), I think using the original art delivered some extra ooomph.

LikeLike

Is there a Sorcerer supplement available or in the works that re-skins demons as an individual’s “super power?” If not, are you still open to folks tinkering with Sorcerer adaptations?

Just curious.

LikeLike

It would work great for plenty of comics I can think of, certainly. I don’t have plans along those lines but I am completely OK with people using the rules or versions of them – that’s been going on for a long time anyway, after all. I’d say go for it, and all I ask is a nice acknowledgment somewhere in there.

Ha … this is so perfect …

LikeLike

Pingback: Oddities and experiments | Comics Madness

Pingback: Presentation: The Death of the Superhero (retrospective re-presentation of a 2018 talk) – Academy and community