Getting it just right

Posted by Ron Edwards

Looking yet again at DC Heroes from 1984 and 1986, design team led by Greg Gorden, published by Mayfair Games, I must say, it’s one of the best bread-and-butter supers RPGs I can think of, possibly even best RPGs period. It is also the harbinger of some of the worst.

Looking yet again at DC Heroes from 1984 and 1986, design team led by Greg Gorden, published by Mayfair Games, I must say, it’s one of the best bread-and-butter supers RPGs I can think of, possibly even best RPGs period. It is also the harbinger of some of the worst.

I didn’t play it, or barely. My 80s game as should be abundantly clear by now was Champions, specifically the mostly-forgotten earlier editions. My main contact with DC Heroes came through some accounts and art in The Clobberin’ Times which mostly disguised the actual game system to slip by the zine’s focus on Champions which was usually enforced. The reported events looked like a lot of fun, concerning a group called the Minutemen (probably inspired by Watchmen, nothing to do with the real-life nativist/supremacist group by that name), and especially a nifty-looking hero called Dr. Python. [I have played and enjoyed the contemporary game Marvel Super Heroes, so this post will get partner about that game one day.]

I was intrigued enough to get the rules and to note some crucial points, which seem more important to me now than back then. FYI: the curse of role-playing at the level of its medium is that the basic shared understanding of what’s happening in the fiction readily breaks down. I call this the Murk. Participants in this hobby, reading this, know exactly what I’m talking about and how frequently it has dogged and ruined the enjoyment of this thing. You have to know what the current scene and situation are, and in some practical way, where your character is and what’s going on. This is conducted solely through dialogue – little miniatures and maps never work by themselve – and through a degree of social attention and commitment to the imagined space.

The considerably more prevalent view was reductive: that the more clarity was established for action by action resolution, then the smallest atoms of these imagined moments would be clear to everyone – and thus, strictly through accumulation, any larger-scale units, regarding major changes in fictional events, time, and place, would be accounted for, and never unclear, from the bottom up. Many RPG designers have dedicated considerable effort toward this end.

The principles at this level include what I call IIEE (intent, initiation, execution, effect), search time and handling time, and outcome authority. RPG titles mostly provide an imitative stew of crapshot design expected to be massaged into function by a group at a table, but there are also some shining lights. The DC Heroes rules have them so well in hand that it takes my breath away.

First, one has the Action Points, representing a design ideal at the time to model any and every physical quantity with a simple scale. DC Heroes takes it even farther to rate characters only in these same terms, so there are no conversions or derived features in the rules.

Many games with the above feature tend to include complex methods of resolution, especially for consequences. In DC Heroes, this is all you need:

There are no bonuses or circumstantial effects beyond single-digit math prior to the roll, always in Action Point units, and you always roll two tend-sided dice to consult the Action Table. Resolution is utterly reliable at this level, no Murk at all – so given the reductive logic, one would think: problem solved.

There are no bonuses or circumstantial effects beyond single-digit math prior to the roll, always in Action Point units, and you always roll two tend-sided dice to consult the Action Table. Resolution is utterly reliable at this level, no Murk at all – so given the reductive logic, one would think: problem solved.

My view differs, in suggesting that there are scale-dependent forms of Murk that must be dealt with specifically on their own, such things as starting and stopping scenes, and how character desires and actions cause and reflect that, or clarifying how we know a larger situation is “done” or not. My published games display a wide range of how this might be accomplished, especially as a consequence of play in the moment, without sacrificing all to the mandate of a single person at the table.

With this is mind, the design for these lowest-level resolution events demands a couple more variables which the “nail it down always” doesn’t serve too well. I call them the Bounce, meaning the unpredictability of resolved actions and ultimately situations based on immediate circumstances, and the fruitful void, meaning enjoyable effects which arise not because they’re listed and named, but because of how the listed-and-named effects may interact in a specific case. Both of them arise directly from the real people’s commitment to the immediate fiction; thus, eliminating Murk is necessary … but not sufficient.

I’ve been looking at these rules again to suss out where they stand regarding these issues, which is often difficult – one must examine not only the specific and clear instructions, but the offhand instructions and assumptions about how we get to punching and how we arrive at whether there’s more to be done. We’re looking at an incredibly robust action-and-resolution system, and that’s a good thing. The question is what it does.

I’ve been looking at these rules again to suss out where they stand regarding these issues, which is often difficult – one must examine not only the specific and clear instructions, but the offhand instructions and assumptions about how we get to punching and how we arrive at whether there’s more to be done. We’re looking at an incredibly robust action-and-resolution system, and that’s a good thing. The question is what it does.

Readers may also be familiar with my long-standing claim that reading a game isn’t good enough; that one must play it, not as a critic or reviewer but as a genuine participant, with a good will to understanding and according with its rules, before forming a position about it. The internet term actual play with this specific meaning, began as Forge jargon.

So, we’re playing it! My copy is a real dinosaur, 1st edition from 1985, which might raise a tear of joy in some of the readers here. I feel kind of bad that the box is bit squished from storage and moves, but fortunately everything inside is in good shape.

My partners in crime are Jerry Grayson, Joel Rojas, and Whitney Barber. Jerry, especially, knows the rules inside and out by edition.

This is Legacy, son of Shango, invented and illustrated and played by Jerry. He’s one of the Fringe Agents, three heroes in Chicago who prefer to work from the shadows and stay low-and-effective at the community level. Legacy is a fairly high-profile hero mainly due to his father’s long career as Shango, but he feels like he does his real work this way. The other two are Burn Agent (Joel) and the Bronzeville Phantom (Whitney), both of whom lean toward the spooky end of the supers scale.

This is Legacy, son of Shango, invented and illustrated and played by Jerry. He’s one of the Fringe Agents, three heroes in Chicago who prefer to work from the shadows and stay low-and-effective at the community level. Legacy is a fairly high-profile hero mainly due to his father’s long career as Shango, but he feels like he does his real work this way. The other two are Burn Agent (Joel) and the Bronzeville Phantom (Whitney), both of whom lean toward the spooky end of the supers scale.

What do you do …? Ah ha! The game rules also provide the subplot procedures, typically provided by the player, and expected to be brought into play as ongoing hassles and context for the hero’s situations. This is, I believe, the first time such rules appeared so explicitly in role-playing, although the biggest Disadvantages in Champions and their clarification in its supplements also served that end. Superheroes are soap operas, no question, and it makes perfect sense that the hobby would fold in relevant rules when this genre got under way in it.

Legacy’s current subplot, for example, concerns his father, the former superhero Shango and, as a Nigerian immigrant to the U.S., one of first black superheroes. Legacy’s powers are explicitly passed from his father to him, with the implication that as the process is completed, his father will at the very least be subject to advanced age, and possibly die.

My interest lies in answering this: does action by action resolution and effect feed directly into changing these contextual situations in unpredictable ways?

Well, there’s a historical contradiction within RPG texts between stories as emergent property vs. stories as completely under GM control. Many, many role-playing texts describe play as “the players completely direct and state the actions of the characters; and the story is guided by and under the control of the GM” – an absurd contradiction I like to call The Impossible Thing Before Breakfast, as in practice one of those things simply has to give way to the other. These are, incidentally, the two competing meanings of “story” in geek culture, and the latter is by far the most prevalent.

In removing the distraction provided by laborious and Murky resolution, DC Heroes lays this question bare. Either its solid resolution system renders every situation completely unpredictable (Bouncy, emergent, fruitful) because who-knows-who is going to do who-knows-what … or it makes the outcome of any situation nicely predictable based on the GM being able to frame it just so and able to repurpose it to the next scene just as he or she wants. Unfortunately, although the introductory material in DC Heroes leans toward the “who knows what will happen, we play to find out,” the explicit, multiple-example, and directive material in the GM’s sections swing it the other way – hard.

Here’s the thing, or rather, two. First, the scenarios and situations the heroes face are fixed as villain-of-the-week confrontations, tuned to a fine art of “the villains do an illegal thing, you hear about it, you find out about it, and you have a chance to stop the big thing they’re doing next. The villains, frankly, are dumb – they just do crimes, period, and by definition, in such a way that a hero is bound to get onto them. They really don’t live up to the golden opportunity provided in character creation, in which (in my edition) you pick the Heroic Motivation first. Choosing villains and their plots well-suited to those motivations seems like a gimme. Even the villainous motivations – discernible only from the DC example characters, and not part of the villain creation methods – are, no pun intended, criminally boring.

Second, the GM sets the opening parameters of every fictional moment, which is to say, – everything’s incredibly predictable, up to and including the spendable resource. The text even recommends rehearsing the hero-villain fights as a matter of preparation, so you can be all ready for anything that can happen during play. If you want them to burn Hero Points, set the difficulties just past their average success range, and you’ll see’em do it. If they’re sucking wind “too soon” relative to stopping the villain, then set up the next circumstance such that they have some advantages.

What all this means, sadly, is that the subplots are intended merely to hum along, and the villain-stopping adventures arrive like clockwork too. There simply is no way for events in play itself to develop the fiction into something unplanned.

If your idea of role-playing is the GM tapping on the players’ tuning forks, posing situations just past their on-paper capabilities to keep the Hero Points cycling, managing the villain-crimes and fights as set-pieces, always knowing what to do next, and rolling the subplots along, then it’s for you. Story creation type 2, “well in hand.” The players’ decisions and their characters actions can look causal, but they really are not.

The timing makes perfect sense for the exact mid-1980s in role-playing history, as the hobby as a whole was seeing a profound shift from “the story is wide open” to “the story is safely in-hand.” This shift arose from a lot of things, including fiction tie-ins, RPGA practices, changes in publishing and distribution, and a culture of Game Master as Fantasy Series Author. The primary agent began with Dragonlance and reached its refined form with Forgotten Realms. For superheroes, Champions was about to display this switch abruptly from the former (1st-3rd editions) to the latter (4th edition, 1989), and DC Heroes appears to me as an almost perfect avatar of the moment, hovering between the two, so that if you tip your head one way, putting some text in bold and softening other text or ignoring it, then the story is wide open, and if you tip it the other, doing the same only with the texts reversed, it’s safely in-hand.

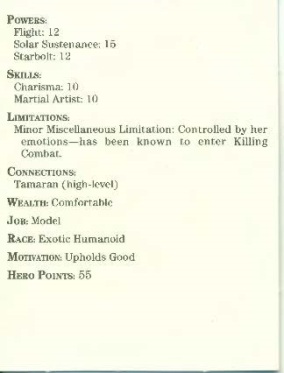

As nicely safe as the Wolfman-Perez The New Teen Titans, the comic which obviously inspires it more than any other, with which I have an admiration/exasperation relationship, and which will be receiving a no doubt unpopular post here in a few days. Here’s Starfire in my rules.

It’s great. But is this the reliable baseline to which we will always return, or is it the jumping-off point for what may come?

It’s great. But is this the reliable baseline to which we will always return, or is it the jumping-off point for what may come?

Both Villains & Vigilantes and Champions are unquestionably the more jury-rigged, unnecessarily math-y, and kooky games, but (in the editions I’m talking about) also unquestionably built to emulate existing superheroes, so you can do what you want, and who knows where your game will go, and who/what the heroes will become. DC Heroes can do this if you squint away much of the text, but as a whole, it finally comes down on the side of simulating existing superheroes – meaning, “getting it right, as we absolutely know what is firmly is” and thereby winds up with … well, with doing exactly that.

In our game, I’m messing with this a little, while also trying to stay within the textual parameters of how to prepare. Given the clarity of the text, it may be possible to isolate the precise “hover point” between the two story types down to the sentences. So look forward to posting about our awesome characters, villains, play-events, and emergent story sometime.

Next: The not so secret cabal

Posted on February 21, 2016, in Supers role-playing and tagged Bounce, DC Heroes RPG, fruitful void, Greg Gorden, IIEE, Impossible Thing Before Breakfast, Jerry Grayson, Joel Rojas, Mayfair Games, Murk, Teen Titans, Whitney Barber. Bookmark the permalink. 15 Comments.

Ron, I still have my original 1st edition of DC Heroes (and the second). I bought it when it came out because I was a DC fan though I never had the chance to play. Have nearly all the sourcebooks and adventure modules too -as reference materials of course. I am looking forward to hearing more about this new campaign.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool. AP = Attribute Point, btw.

LikeLike

Right – I meant Hero Points, HPs. Hey, they’re all in the same units …

LikeLike

How do Kickers from Sorcerer differ from Motivations in DC Heroes? Kickers are certainly more specific, but they both offer the context from which the GM will frame the next scene/session. In either case, the player is unlikely to be surprised of how the session opens but the question seems to be: where does it go from there? This may be a mechanical obstacle; the Hero Point economy certainly makes DC Heroes harder to improvise, but I wonder if even that could be navigated. I agree that the text expects the GM to run a more scripted arc.

LikeLike

Seems to me that the Motivations can be like Kickers only with extensive rules re-working and aggressive re-interpretation. They don’t include a specific player-authored scene that the GM must incorporate as serious business, not merely as a hook into a pre-planned third-party situation. As written, they’re more like psychological profiles – in fact, pretty much irrelevant because, taking the rest of the game’s instructions into account, any hero with any Motivation can be thrown up against any villain, genuinely at random.

One has to beware projecting into the text too. I definitely see the Motivations as integrated with the Subplot rules, “obviously” so … but you see, that’s my reading and habits of play getting involved, not what the text really says.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Got it. I too integrated Motivations with Sub-plots as one part although the rules don’t support how to use those elements together and _may_ even contradict them. The text does not explicitly offer guidance on that front.

LikeLike

I’ve been meaning to get my hands on a copy of DCH for decades now; it’s the one ’80s SHRPG with which I have absolutely no experience.

Aside: Ron, is Chaosium’s Superworld on your radar?

LikeLike

I remember its promotion all the way back when. But I’ve never seen it.

LikeLike

There was some interesting contemporary commentary from the designers (I don’t recall precisely where, sorry) about their approach to the game. As I recall, they talked about pinning down various DC writers and editors and positing them a scenario where Superman, Wonder Woman, Martian Manhunter and other characters are all trapped and bound and absolutely cannot escape and are being bombarded with mega-deadly death-rays, and asked the writers who dies first, second and so on, in order to figure out the character’s game stats.

It occurred to me years later how that approach, intended to show how much the designers were striving to make the game accurate to the source, was really doing the opposite. The question isn’t “how long does it take to kill Superman?” as if he’s a high-level D&D Paladin with a vast but finite store of hit points, but “how does Superman, the *protagonist*, escape the unescapable death trap? Because that’s what Superman does.” Looking back, it’s interesting to recognize the dissonance created from a tactical mindset applied to a narrative genre.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a bunch of meaningless malarkey. I have to assume you never actually played the game, possibly never even read it, if this is your interpretation. Lots of self-serving mumbo-jumbo in a desperate bid to appear intellectual. Where did the bad GM touch you to make you act out this way?

LikeLike

Congratulations! You have achieved the most worthless attempt at a drive-by at the blog thus far. Is it possible to chew up the scenery with missed shots if they’re all blanks? Marvin proves it is, trollin’ like it’s 1999!

Try finding a thing in the post actually to critique, which entails reading the little word-things in sequence. No sign so far that you did that yet.

Speaking of things to find, your dick is probably around there someplace. It’s more fun to masturbate using it than the keyboard. You’re welcome!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Top Book Bloggers of 2016 – castaliahouse.com

Pingback: Being, having, and nothingness | Comics Madness

Pingback: Dynamic mechanics | Comics Madness

Pingback: A fearful symmetry is born | Comics Madness