The not so secret cabal

Posted by Ron Edwards

In the course of scribbling our vigilante posts and rejoinders therein, Steve and I realized something. It’s incredibly obvious and I wouldn’t be surprised if we were greeted with a collective, “Everyone knows that!”, but as it happens, well, I didn’t. So here.

The series so far includes Eat hot lead, comics reader, What was the question again?, The Big Bang, Wicked good, Vigilantes R Us, and In Darkest Knight. This one relies on the back-and-forth history between Marvel and DC in the 70s and 80s described in And the horse you rode in on, with help from The Comic Book Heroes.

RON COUNTS ON HIS FINGERS

O’Neil and Giordano

Robbins and Bob Brown

I doubt I need to elaborate on the revision of Batman away from the established comedic 60s character around-and-about 1970 through 1975 or so. My present point is that it didn’t occur in a single title or by a single creator’s hand. Denny O’Neil and/or Neal Adams (meaning, together or with different artists and writers, respectively) played a big role, but as writers, so did Len Wein, Archie Goodwin, and Frank Robbins (who with Adams introduced the Man-Bat), and the short series by Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers is a classic all on its own. I don’t know whether or how Marv Wolfman participated; it seems his sort of thing, but I’m not so good on detailed DC history, so will defer to anyone who does know.

O’Neil and Adams

Robbins and Adams

I think the starting insight is that this era’s The Batman, “the Dark Night Detective,” emerged as a composite from at least four authors and several artists. A number of other important and lasting characterizations kicked in here too, especially restoring the Joker as a mass-murdering maniac. (Whether all this is a return to the pulp Kane Batman of the 1930s or a new thing of its own, I dunno. For what it’s worth, that Batman did rack up a body count.)

The next is to see how this corps has been the core of the development of the vigilante and/or more-violent and/or slightly unhinged hero throughout the roughly 20-year history that Steve and I are writing about. One piece that can’t be missed is Goodwin’s and Walt Simonson’s original Manhunter series, a six-issue backup in Detective Comics. But the main and more experimental creative phase happened at Marvel, and then shifted to DC again after about a decade.

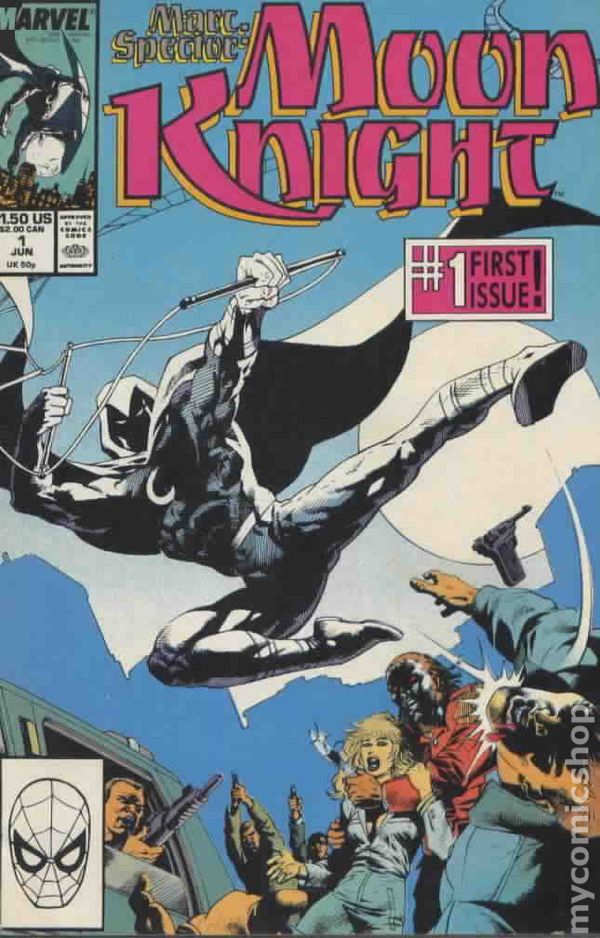

- During the mid-70s, Wolfman and Wein were writers and highly-placed editors at Marvel, even, briefly, with each as editor-in-chief. During this period Gerry Conway introduced the Punisher, who was elaborated by Wein and also by Goodwin as described in Eat hot lead, comics reader. That same year and under Wolfman’s editorship, Doug Moench introduced Moon Knight in Werewolf by Night and kept shoehorning him into other stuff as the next few years proceeded. Moon Knight would pave the way for new vigilantes to gain title status.

- In the late 70s through the early-mid 80s, O’Neil was an editor at Marvel, overseeing both Frank Miller’s Daredevil – which I do regard as a vigilante title – and Moench’s Moon Knight featuring Bill Sienkiewicz for art. (Funny how hard it is for me to process O’Neil as a major presence at Marvel, although his impact is as plain as day.) Keep on eye on all of the creative teams, including Klaus Janson inks for the former and, briefly, Rick Magyar’s inks for the latter.

- Back at DC, during the heyday of the above titles, Wolfman (with George Perez) introduced the Vigilante in The New Teen Titans. Also, Moench became a primary writer on Batman; and then in 1986 came the famous events of Miller’s/Janson’s The Dark Knight Returns and Miller’s/Mazzuchelli’s Batman: Year One, both overseen by O’Neil as editor.

- O’Neil is also editor for Batman: Year Two, written by Mike Barr, illustrated first by Alan Davis and then by Todd MacFarlane.

- Just to top that off, in 1987-89, O’Neil writes The Question with Denys Cowan and Rick Magyar on the art.

Right then: the vigilante “trend” is misnamed; it’s not a repeated independent phenomenon but the product of a surprisingly small body of participants, all of whom knew one another and had worked closely back-and-forth in various ways.

Obviously, O’Neil has been a serious individual player throughout, and given comments – entirely professional ones – from creators working with him (e.g. Frank Miller and Klaus Janson re: Daredevil, 1981 interview reprinted in Marvel Editions: Daredevil #2), he is a proactive editor, involved in story conferencing, character development, and thematic discussions. I gained a lot by considering his simultaneous editorship over Moon Knight and Daredevil, the former aimed at newsstand distribution and labeled with the Comics Code Authority, and the latter direct-only and with no Code, while interpreting his early writing on Batman and his later on The Question more or less as bookends.

Obviously, O’Neil has been a serious individual player throughout, and given comments – entirely professional ones – from creators working with him (e.g. Frank Miller and Klaus Janson re: Daredevil, 1981 interview reprinted in Marvel Editions: Daredevil #2), he is a proactive editor, involved in story conferencing, character development, and thematic discussions. I gained a lot by considering his simultaneous editorship over Moon Knight and Daredevil, the former aimed at newsstand distribution and labeled with the Comics Code Authority, and the latter direct-only and with no Code, while interpreting his early writing on Batman and his later on The Question more or less as bookends.

In doing so, I think one can assemble O’Neil’s hero, meaning, a set of components which have apparently been important to him. I’ll stress that I don’t think the four primary characters I’m talking about are merely “skins” for it, but they certainly partake of it. I also stress that this isn’t supposed to be Batman in an “is” or essential sense; it’s what O’Neil helped to make of Batman and, I speculate, contributed to making for these other characters as well.

- an isolated personal life, including past and ongoing rejections of those who would become closer,

- ongoing rejection of sex in favor of “out for justice tonight,”

- explicit non-super-powered physique and the effort it takes to keep in peak physical condition

- strong emphasis on a street patrol and policing role,

- absolutely will not kill (and aided by the plot in never doing so accidentally),

- identifiable mental instability especially regarding anger, but not clinical or out of control,

- vehement disapproval of guns,

- low-level but ongoing pop mysticism,

- reduction of the human person into a mask of its own, corresponding to the elevation of the character-mask into a motivated force,

- politically, perhaps the term “dissenting angry liberal” is the best summary, meaning frustration with institutions and feeling forced to maintain humanist ideals with one’s fingernails and teeth [I use the term “liberal” in one of its older meanings, nothing to do with today’s political rhetoric]

Scoping out again to the larger (if only slightly) body of work among all these creators, you can find some differing views here and there, differing standards for social contexts and values, but the range really isn’t that wide. The big change comes – often involving the same characters – when entirely other primary creators become involved. It’s like an orthogonal invasion, displaying striking differences and a whole new sort of political conundrum.

- Steven Grant, after writing the vigilante title Whisper at First Comics; in 1986 he comes in to do both the Punisher: War Journal mini-series and, in 1989, Moon Knight

- Mike Baron, after writing Nexus and The Badger at Capital Comics and then First Comics, both vigilantes; in 1986-87 he comes in to begin the Punisher series.

- In 1986-87, Alan Moore comes in with Watchmen and Rorschach.

There are deep waters here. Almost all of the early 70s contributors to the gritty vigilante books were generally leftish and sometimes pretty radical, and the typical foes, when they’re not badly-written villains-of-the-week, were organized crime with one foot in the police/political establishment, CIA crazy-assholes straight out of the current Pike and Church investigation results, and rich right-wing loonies.

The late-70s/early 80s don’t change this model much, but they do bring in some murky new tropes, including street gangs full of weird multi-racial mohawked juvies-who-look-thirty, egregious crazy-terrorist Arabs, and the Golan-Globus staple of revolving door courtrooms which unleash obvious psychos to make the streets unsafe for ordinary folks.

With 1986, are we looking at straightforward right-wing appropriation? I think it’s not that simple, textually. That phenomenon might be worth a post. It might however, be an accurate observation about the audience, especially those who take Judge Dredd literally, or pump fist-circles at Rorschach’s initial rants.

STEVE COUNTS ON HIS TOES

By and large I can’t really disagree with any of this — after all, it’s a theory we sort of jawed out the basics of during long phone conversations and then fleshed out with our reading. But the salient fact — Denny O’Neil’s editorship — is the key regardless of who did the main writing.

To address your concluding question, I don’t think this is a straightforward “right-wing appropriation” per se, but more a reflection of the times. Reagan is in office, with his firm and unwavering stance about “the evil empire” and other problems facing America. And then comes 1984: the year of both the Bernard Goetz “subway vigilante” incident and the introduction of crack cocaine into America’s cities. At that point crime had been on the upswing since the late Sixties. Crack just made the situation worse, and people were looking to the likes of Reagan and Rudy Giuliani to make their lives safer. In the comics that urge translates, I think, into a harder edge for many superheroes, the advent of the Bronze Age, and the rise of vigilante characters. As you say, this is perhaps more driven by what the audience wants than what the creators think and believe. Or maybe it’s just that back then, creators like O’Neil (who wrote the famously left-wing “Green Arrow and Green Lantern road trip” story) were better at keeping their politics to themselves and just writing good stories regardless of whether they “believed” in them.

It would take more knowledgeable commentators than I to address the issue of whether the early Seventies “darkening” of Batman is a new thing or a return to the earliest Batman stories of Finger and Kane, but it’s a fascinating question perhaps worth delving into at a later date after we both have time to read a lot more comics. Or maybe get the chance to ambush Denny O’Neil at a comics con and ask him a bunch of questions.

RON’S FINISH

True: this wasn’t a debate topic so much as a mutual “doink.”

My thinking on the politics – putting aside my response to the implication that the Soviets constituted a “problem for America” – is that the security/paranoia issue of the 80s is very much a New York thing, or took on specific features there which were disseminated throughout the country through mass media. I regard Giuliani’s reign there as nothing less than a catastrophe, but I also think it was a mere symptom of New Yorkers undergoing an upswing in ethnic hate, in class divisions, in insularity (as if they needed it), in Zionism, in street-fear, and a weird intermixed fear of and dependency upon police. And Marvel and DC are New York through and through, what Colin Woodard calls the New Netherlands.

In reference to the Finger/Kane Batman, I’m lucky to have my copy of The Steranko History of Comics, Volume 1, which – and remember this is from 1970 – tells us about the expressionist art, the purple prose, his original long bat-ears, cape which was constructed as ribbed wings, and finned gloves, as well as the preceding “the.” So the O’Neil/et cetera “the Batman” does seem specifically tuned to the original imagery. Steranko also directly ties the comics character to pulp fiction inspirations via Finger’s account, and if the creators we’ve mentioned in this column weren’t reading this same volume, I’ll eat my copy.

What really interests me now is the gun thing. Batman actually packs a pistol in some early issues, but that’s replaced – and this is still in the ’30s – by a code against killing, albeit the kind that you occasionally set aside “when necessary.” He even mows down some mutated monster-guys (who used to be people) with a machine gun, thinking “I hate to do this” as he goes. Huh – I’d forgotten that the Comics Code Authority was preceded by DC’s in-house Comics Code, and that during its formation around this time (1940, the year which also introduced Robin), Batman was forbidden ever to carry or use a gun.

It seems that when Batman’s brought back to his roots in the 70s, that’s the one feature that squirms around or among the DC Code and the earlier “sequential-art pulps.” It’s developed into a major issue during the 80s, both psychological and societal, throughout the whole trajectory of the Punisher, Miller’s Daredevil (including his clash with the Punisher), and Moench’s Moon Knight (including the distinctive squelching of the Marc Spector identity). It also gives me new appreciation for the machine-gunning the “mutant” (gang member) in The Dark Knight Returns as a genuine callback rather than merely gratuitous splatter, as well as a new lens to examine Batman: Year Two.

Next: Sheba knows her daddy

Posted on February 25, 2016, in Vulgar speculation and tagged Alan Moore, Batman, Bill Sienkiewicz, Daredevil, DC Comics, Dennis O'Neil, Frank Miller, Mike Baron, Moon Knight, Neal Adams, Steven Grant, The Comic Book Heroes, vigilante. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

You guys probably know this, but in the interest of clear sequencing: Giuliani didn’t run for NYC Mayor until the ’89 election, and didn’t win until ’93. He was (disturbingly, I’d say) political in his various roles with the Justice department in the 80’s, but he wasn’t an elected official until the 90’s.

Which maybe just highlights the 80’s as a battlefield for “controlling the narrative”. Making these 80’s comics characters and their potential 90’s appropriation even more interesting.

A bit on the gun thing, and the strangeness of NYC politics: Giuliani initially failed to get support from the Conservative party in NYC because, among other reasons, he endorsed the Liberal party position on gun control (yes, Liberal/Conservative as potentially – and sometimes actually – separate from Republican/Democrat on the ballot).

Another bit you’ve probably considered, connected to “no guns” and the 70’s/80’s (and maybe NYC/Guardian Angels) – the growth of Martial Arts, both as myth and actual phenomena.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The martial arts thing is huge. These creators were in the first U.S. “karate generation,” in the teens to see the first commercial martial arts schools. Most of it was Shoto-Kan Karate, the national/military techniques, quickly adapted to the American commercial method. Back then it was all called karate in the U.S., pronounced “kuh-rotty” as we know. Then in the late 60s, all this new stuff managed to brand itself: Ed Parker’s Kenpo karate, later just Kenpo; Bruce Lee’s jeet kune do; kung fu pretty much meaning “what I saw in that movie;” the particular high-branding franchise version of Tae Kwon Do (spelled thusly; not the same as taekwondo or Taekwon-Do), and savate. A lot of this was very Americanized, especially in the New York and Los Angeles areas. Many other forms were present (Cuong Nhu, Tai Chi, Aikido …) but not well-branded or in the common vocabulary.

So, up through the mid-70s, comics, movies, and TV fights looked like boxing with tackles, often wrestling, with fancy kicking and “karate chops” being reserved for especially exotic fighters. Then when this very time we’re writing about gets going, you see all these newly common-vocabulary things come in. Walt Simonson was one of the artistic contributors. Doug Moench was probably the leading writer for it, featuring Moon Knight with his savate kicks and obviously, his highly technical Master of Kung Fu, but you can tell all these guys were into it. Nunchucks (so pronounced) everywhere, lots of palm strikes knocking heads back and finger-strikes to the throat, No one really knew how to draw the advanced kicks, so really long front kicks were typical.

Comics pretty much track movies – when Golan Globus started doing all their “find a champion in something and put him in a franchise with Death, Iron, Fight, Fist, or Blood in the title,” fights in comics started looking like full-contact martial arts: a boxing-ish version of older Taekwon-Do. Then of course, bringing in the new hot franchise, Ninjitsu. Since no one knew what ninjitsu looks like because it’s not a real thing (not counting the real martial arts taught today under that name, which are what they are on a case by case basis), they basically made it up to form the stuff that showed up in the comics. The pioneer there was Daredevil by Frank Miller, influenced by a lot of Japanese comics – some people may not know the Turtles were a point-for-point parody of his ninja storyline.

LikeLike

Pingback: A pretty butterfly | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Jet and silver | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Red goggles at midnight | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Irish rage, Catholic guilt | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Justice is served! | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Lurking everywhere | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Actions have consequences | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: No pants necessary | Comics Madness

Pingback: Kill, kill, kill | Comics Madness

Pingback: Batpulp | Comics Madness