The way underground

Hey, I kept this post mostly SFW but most of the links in it go to a great big NOT SFW, so go ahead and click on those and lose your job, if you want.

There were a lot of other comics around during my childhood besides the ones I bought at the newsstand, spelled a wee bit differently. The “x” probably comes from the title of Zap Comix; I’m not convinced it has anything to do with the MPAA X-rating (as claimed in Roger Sabin’s Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels), which was invented a little bit later. It’s hard to define them, as sometimes it was about self-publishing, and sometimes a stylistic thing, especially the balloony-cartoony look, and sometimes about the content (don’t say I didn’t warn you). It’s possible that the only real unifying feature was that they weren’t in ordinary comics distribution and were effectively invisible to it, or to any imaginable means of regulation. More than once, an intended one-off issue included a “subscribe” address mainly as a joke, but which turned into actual subscriptions and a scramble to put together some kind of staff and schedule. They were published any which way, distributed by hand or by direct mail-order, and sometimes in head shops or weird stores of any kind. All I can say is that the available volume was incredible, they were everywhere, everyone had them.

It’s absurd to list or try to catalogue titles here: even saying Zap, Snatch, or Yellow Dog misses the point that there were dozens and dozens of titles, often merely a single issue, as well as magazines like witzend (begun by Wally Wood) that featured a ton of stuff, and a constant array of running strips or backup features in multiple other publications, such as underground newspapers like The Berkeley Barb and The East Village Other, or Vaughn Bode’s work in National Lampoon and Cavalier. If you add poster and album cover art, as you should, then collections or bootlegs of those become part of the library. One should also understand that there’s no real starting point to the phenomenon, going back to Tijuana Bibles if you like, or the edgier EC and similar comics of the 1950s, Harvey Kurtzman of course and possibly William Gaines himself.

In the current discourse, everyone talks about Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, S. Clay Wilson, Jay Lynch, Rick Griffin, Harvey Pekar, Denis Kitchen, Spain, Kim Deitch … but I suggest looking at everyone else too. You’ll notice a few more familiar names cropping up: Wally Wood as mentioned above, Richard Corben, Jeff Jones, Basil Wolverton, Mike Ploog, and Alex Toth, among others. Also, don’t miss the presence of women writers and artists, just as wickedly incisive or weirdly artistic as the men, and equally explicit. The most famous is Trina Robbins, but again, once you go looking there’s a surprising list that produces more familiar names than you might think.

In the many, many households and wide variety of people I encountered in my childhood, these comics were often scattered about. I remember reading tons of them, including some incredibly raunchy stuff I can’t believe I saw before I was ten, like Crumb’s infamous “Fuck-In” and a lot of similar material. Good for me? Bad for me? I can’t say. Remember, I grew up with skinny-dipping and by this time had seen and socialized with literally hundreds of naked adults and kids. Although my own house didn’t accumulate comix, we did have such things as The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics (which was very insane) and an early collection of Rick Griffin art.

I can’t remember how I got into a copy of Mark James Estren’s A History of Underground Comix (1974) but the images and text in there were indelibly printed into my mind, so I must have been able to peruse it over and over, I’m thinking at about age 12. I wish more kids my generation had learned about drugs and sex and political hassles this way; one gets buffeted by all the details and observations from the adults and surrounding world without any explanation, and it helped a lot. It’s thoughtful, interesting, and inspiring, providing immense context and raising all the right questions for a bright kid to process the extreme imagery. Acquiring the reprint published in 1982 was a joyous occasion for me. Anyone who wants to understand comics history needs this book. [the later reprints have a different cover]

I can’t remember how I got into a copy of Mark James Estren’s A History of Underground Comix (1974) but the images and text in there were indelibly printed into my mind, so I must have been able to peruse it over and over, I’m thinking at about age 12. I wish more kids my generation had learned about drugs and sex and political hassles this way; one gets buffeted by all the details and observations from the adults and surrounding world without any explanation, and it helped a lot. It’s thoughtful, interesting, and inspiring, providing immense context and raising all the right questions for a bright kid to process the extreme imagery. Acquiring the reprint published in 1982 was a joyous occasion for me. Anyone who wants to understand comics history needs this book. [the later reprints have a different cover]

If I’d have to choose a favorite artist, the near-winner would be Rand Holmes, partly due to his likeable hero Harold Hedd, but especially because, well …

First place has to go to the incomparable Vaughn Bode; I was and am a huge Cheech Wizard fan, and this and this were very big posters on my wall for most of my life. I like Pekar’s writing well enough and love his synergy with artists. S. Clay Wilson will scar you, but I confess I find most of it hilarious. The Furry Freak Brothers were also always a fave – I never could figure out why people are so stupid about this title, not understanding that it’s spoofing drugs and hippiedom just as hard as the establishment, although in the pinch it does choose a side and therefore gains some weight. I got a kick out of Wonder Warthog and recently made sure to nab the collection. I’d drop some good money on George Metzger’s Moondog in a nice reprint collection, if anyone’s listening.

If you’d like to see my tiny homage to all of this, see the Trollbabe Comix I did with a number of artists in 2004-2007 or so. It’s a pretty good story! The fact that it completely baffled my role-playing customer/audience base was a sharp lesson for me.

But that’s enough review; there are many websites dedicated to the topic. Here I want to talk about the extensive crossover between underground and newsstand comics during this period, maybe 1968 through 1977 (I guess). Way more than you might think. Marvel was itself sort of an underground publisher for a while, in two ways. First, various creators subverted oversight by acting as one another’s proofreaders, so as long as they didn’t kick off the characteristically literalist and frankly stupid Code people, they could do whatever they wanted. Therefore some of stuff which hit the stands labeled “Marvel” was not too far from a covert little shop of crazy guys having fun but also deadly serious about certain things, typically Englehart, Starlin, Gerber, and McGregor. This seems to have gone on more-or-less from 1971 to about 1976. (Denny O’Neill certainly could get acknowledged this way too, over at DC.)

That point gets a lot more literal when you examine the indie-Marvel-indie-Marvel careers of Gene Day and Frank Thorne, both of whom served as influences and mentors to the Pinis doing Elfquest and Dave Sim doing Cerebus the Aardvark – both of which are nothing but the purest underground work imaginable in all but name. “Comix” might have become bad box office, but all you had to do was not use the term. Neither the Pinis nor Sim ever worked for Marvel but without those Marvel-underground hybrid influences/mentors, I don’t think their comics would have launched and maintained themselves as successfully.

Second, Stan Lee did one of his rare executive actions by connecting with Denis Kitchen to produce the Comix Book (1974-1976), which I see unfairly dismissed in various accounts as a curiosity or a stunt (the current Wikipedia page presumes Lee merely “capitalized on” the undergrounds), or wrongly described as watered down in terms of explicitness. The latter point first: it’s true, there were no Crumb or Wilson-style ridgy hard-ons or oozing vulvas, but lots of “real” underground stuff didn’t have those either, and it did in fact display about as much nudity and crudity as most of them, as well as some genuinely great social satire. For the former point, in acquiring the recent collection (The Best of …), I was surprised to see the heavy hitters included in there, such as Robbins, Spain (!), Wilson (!!), Spiegelman, and more. Robbins’ Panthea deserves a post of her own, and I’m tempted to see her as the prompter for all those kittycat heroines at Marvel of the later 70s. Reading the letters and looking at the editorial decisions, I can only conclude that Stan Lee personally enjoyed underground comix and really did want to get the creators into national distribution. You can bleat your Friedmanite cant about “sales” all you want, but looking at the dates, you’ll have to work hard to convince me that either Landau or Gaulton didn’t kill the Comix Book dead with a single “we own it you do it” meeting.

Second, Stan Lee did one of his rare executive actions by connecting with Denis Kitchen to produce the Comix Book (1974-1976), which I see unfairly dismissed in various accounts as a curiosity or a stunt (the current Wikipedia page presumes Lee merely “capitalized on” the undergrounds), or wrongly described as watered down in terms of explicitness. The latter point first: it’s true, there were no Crumb or Wilson-style ridgy hard-ons or oozing vulvas, but lots of “real” underground stuff didn’t have those either, and it did in fact display about as much nudity and crudity as most of them, as well as some genuinely great social satire. For the former point, in acquiring the recent collection (The Best of …), I was surprised to see the heavy hitters included in there, such as Robbins, Spain (!), Wilson (!!), Spiegelman, and more. Robbins’ Panthea deserves a post of her own, and I’m tempted to see her as the prompter for all those kittycat heroines at Marvel of the later 70s. Reading the letters and looking at the editorial decisions, I can only conclude that Stan Lee personally enjoyed underground comix and really did want to get the creators into national distribution. You can bleat your Friedmanite cant about “sales” all you want, but looking at the dates, you’ll have to work hard to convince me that either Landau or Gaulton didn’t kill the Comix Book dead with a single “we own it you do it” meeting.

To me as a reader, this content was all continuous, from caricatures of Nixon in The Furry Freak Brothers to the barely-unnamed Nixon blowing his own brains out in the Oval Office in Captain America. Or reading both Rick Griffin and Warlock, which absolutely correspond to the uber-trippy work by Kirby, Ditko, and Steranko in the 60s. I cannot possibly be the only person who experienced it all this way, and the historical connections are strong enough for me to infer that it was real.

Yet Howe’s book and my other histories totally skate past it. There’s an indelible accepted wisdom that underground comix were their own isolated thing, that they peaked in 1972 or so, and then “died out” in some kind of organic or market process. This isn’t wisdom, it’s a blatant lie. A couple of really important things did happen to create that lie and cement it into place.

In 1971, the Nixon administration cut a deal with the FCC to withhold radio air play from bands which advertised in underground newpapers and magazines, putting most of them out of business almost immediately. This destroyed the network of mobilizing for protests and communicating across different activist groups, it effectively gutted pop music politically, and it killed the primary venue for underground comix.

In 1973 or so, the legal troubles about “obscenity” began. This all ties into the long-term throughline for Kitchen Sink Press, Bud Plant, and Last Gasp, which is way too much to go into here, but the immediate point is that whatever chance the comix had to get into any sort of bulk-buy distribution vanished faster than a snowflake in hell, and repeating the mantra that they were “dead” became industry dogma.

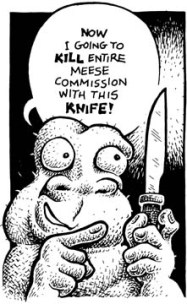

The legals effectively culminated in 1986 with the so-called Meese Report for the Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography, as crocked a crock as was ever crocked. Its important result? Permitting a local community to define “obscene,” meaning, whatever group decides to pillory a comics store (an easy cultural target) gets to decide legally whether it’s guilty in the first place. I call special attention to the testimony of one Andrea Dworkin for the Commission, who aided and abetted their puritanic, rightwing conclusions regarding actual porn (the kind with photography) with enthusiasm and public support, and who therefore may be identified as a primary destroyer of sex work reform in modern times.

In the environment of the mid-70s to the mid-80s, there was no observable stopping point for comix; claiming so is a matter of mistakenly focusing on individual titles. The varying drives toward independent publishing and untrammeled content continued into the difficult history of Eclipse Comics and First Comics. Both represented a convergence of disgruntled Marvel and DC creators and embattled undergrounders, which artistically is a match made in heaven, but without either some utterly legitimate angel-type publisher and distributor, or a culture of constantly printing cheap issues and completely informally distributing and selling them anywhere, they were financially doomed.

I am a little ambivalent about Heavy Metal (the 1977 U.S. license for Métal Hurlant) for complex reasons that aren’t too interesting here, but it did provide break-in exposure for many creators like Matt Howarth who were comix all the way without the term. I am definitely ambivalent about Fantagraphics, which has done fine work in preserving comix somewhat with Love & Rockets, Hate, and others, along with a steady stream of out-and-out European smut if one cares about that one way or another, but which also completely divorced itself from genuine contact with “ordinary comics,” fostering a sneering highbrow mentality (which doesn’t, you know, mesh with yet another Manara collection) and completely missing the opportuntity to foster freedom of publication rather than the editors’ cherry-picked favorites.

Since the 80s, it’s been “underground? what underground?” All the fanfare at Maus‘ appearance neglected to mention its extensive history in that scene, even when the text itself includes one of Spiegelman’s early stories. Everyone “knew” they were dead, but shoot, Zap technically remained in print until 2005 when it closed out with #15 (#16 is in the collected edition). Pekar and Crumb never stopped publishing. Jack Katz kept plugging away at The First Kingdom and finished it. Donna Barr’s The Desert Peach merrily stomped on anything decent about decency issue after issue, as did Howarth’s Those Annoying Post Bros. If Matt Groening’s Life in Hell wasn’t comix, then nothing is. The “Single Page” feature in Cerebus was practically a catalogue/anthology of comix of the day. I suppose you haven’t read any Maurice Vellekoop? Pity. Oh, and one simply doesn’t get more classically ridgy hard-ons comix than Dori Seda and Mary Fleener, both of whom completely obviate all narratives about sexist pig underground comix porn guys in Manichean opposition to some shrewish caricature of feminism. Real-live anti-establishment feminism was in on underground comix from the start and Fleener’s, Seda’s, and many other women’s work show that it remained there and is still there. I wish someone would notice that besides me. Back to my point, Raw began in 1980, Drawn & Quartlerly in 1990. If it’s arty, is it comix? If it’s indie? Are we going to start parsing the difference between “brand” and “label” now? (hint: no)

I’m saying the underground was and is still there … guess where, it’s right there in the name. You have to know how to look.

I don’t think I’ll ever be able to explain to people who didn’t see it how commercially bottlenecked pop culture became in the 1980s and 90s, such that all our music, comics, and movies since then represent a tiny and highly branding-defined fraction of the creative diversity that existed at low-tech, unmanageable, grassroots distribution before then. Even today’s internet provides the means without the fuel, as the cultural understanding that led such work to blossom like that had been largely killed off. It wasn’t some kind of metaphysical “mood of the nation” as if it were a change in the weather. It wasn’t “the market” or some inevitable organizational development by which the activity actually died. It was a specific and concrete set of actions and infrastructure, which rendered the comix commercially invisible and socially unacceptable, so that today’s are farther underground than they were even in the 1940s and 1950s.

But they still live on in my head, all the time.

Links: Comic Book Legal Defense Fund

Next: This one

Posted on May 21, 2015, in Commerce, Politics dammit, The 70s me, Vulgar speculation and tagged A History of Underground Comix, Andrea Dworkin, Art Spiegelman, Cerebus, Dave Sim, Denis Kitchen, Dori Seda, Eclipse Comics, Fantagraphics, Frank Thorne, Gene Day, Mark James Estren, Mary Fleener, Matt Howarth, Meese Commission on Pornography, Oodles of titles, Rand Holmes, Rick Griffin, Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, The Comix Book, The Furry Freak Brothers, Trina Robbins, Vaughn Bode, Wendy Pini, Wonder Warthog, Zap Comix. Bookmark the permalink. 14 Comments.

Hi Ron! You talk about a lot of things this time, so I will number my comments.

1) What’s about the early 70s and kids reading comics full of sex and naked women? Here’s an example of what I was reading (among many other more appropriate titles) from when I was 8 years old (attn: very NSFW images)

Naughty Italians!

Naughty Italians!

Naughty Italians

(yes, the last one is Snow White waking up Prince Charming. And not with a kiss)

I especially liked this one, it was well drawn and often very funny (in a very crass way, perfect with my tastes at the time…)

Naughty Italians!

Naughty Italians!

These are, obviously, the (in)famous “erotic fumetti” that flooded Italian newstands from the late 60s until the early 80s. They were everywhere, every house had them, and nobody worried too much about children reading them. Everybody did.

And even if I preferred the funny ones, some were not funny at all…

Naughty Italians!

Naughty Italians!

I must confess that I thought it was a peculiar Italian experience, and that in old puritan USA children could read only Superman or Batman, or with Red Sonja at most, without any contact with more “sinful” material, and that you could find underground comix only if you were an adult and only in adult stores. Nothing I did read about the history of comics in the USA made me doubt this. This is the first time I have read anybody in the USA describe a comparable availability of “adult comics” in every house.

By the way, seeing what children that did grow up in a more conservative environment ended up, I still think that all these sex comics had a more positive than negative effects on people’s education and maturity. The very few guys that I did know that were not allowed to read these comics from very religious families ended up being the worst girl-hating misogynist I have ever seen in high school…

There was a big difference between the underground comics you posted about and the ones I linked above: the ones I linked above were not “underground” at all. They were sold in the same exact newstands where I could buy Mickey Mouse, and often the newstands had a single “comics” section where you could find both. We did not have the comics code (there was something similar in the 60s but it was very short-lived, ineffectual and everybody ignored it), and newstands had a public license that gave them a lot of advantages, but they were required to carry everything (it was much more nuanced than that, obviously, but that was the final effect)

This means that “sex” here was published by “normal” publishers (even if specialized one – no “respectable” publisher would have published that stuff risking the ire of the Church), not by “underground” ones, and so we did not have anything similar to that underground explosion. There was something, some self-published fanzine, but they had very small circulations and sales.

I am posting this now because I am worried about some computer glitch erasing the post, I will talk later about the other points you touched in your post.

LikeLike

I was pleased to see at least one G+ commenter confirm my experience about their American presence.

LikeLike

Ron please turn these images into links! I didn’t know that the blog software would have done that!!!!

LikeLike

Fixed. BUT – please limit your number of links. I have it set to three or else the post goes into moderation.

LikeLike

Hey Ron! Finally got some time, and really liked your “underground” piece. What I love the most about comix, is the utter grass roots origins they have, particularly as a tool for those artists that thought outside the box. Like all comics, the undergrounds had their period, and would transform into a new model, more accessible both to creators and readers alike. As social mores change with generations, “comix” will always reflect the approaches and attitudes of the outsiders, their art always regulated to their own types of expression and distribution. So does the word “comix” reflect a particular time period of comics? I’d like to think that while it may have been coined in the undergrounds, “comix” refers to me primarily as a more personal, perhaps confrontational type of experience between the creator and the witness.

When one sees such later publishing efforts as Star Reach, and the later Weirdo, it is evident “comix” will always be a part of the pantheon, a place well deserved, if not always observed.

Thanks again for the insights. I WILL be back!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Vernon! Great to see you. It’s especially fitting that I just read Weapon Brown, which I just bought as you know, and what I really liked about it was how it captured two things. In general, that most newspaper comics strips had relatively strong, often subversive or just naughty roots, or some kind of depth which doesn’t match the narrative that “family comic strips” were all sweet and boring. More specifically, that my earliest experience of Peanuts was completely mixed up with the Mad Magazine parodies, which in the late 60s were pretty raw – but corresponded as well to some of the actual strip’s genuinely harsher content. So “my” Peanuts was a weird personal blend until much later when I figured out that the real strip, the parodies, and the TV specials were different things.

It raises the interesting question though: if the word “comix” has any content-based meaning, how could Weapon Brown be considered anything but? One of the most harped-on points during the obscenity legal battles from ’73 through ’86 was how the comix parodies of Nancy and many others were literally attacks upon America’s decency, and thus FIrst Amendment protection of parody didn’t apply. I don’t have to guess what Meese & Co. (including Dworkin) would have made of this depiction of Linus, Sally, and the Great Pumpkin.

LikeLike

Pingback: Long live Lib | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: It was already happening | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Faster, pussycat | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Go to hell and burn | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Sex and sex and sex and sex | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: What was the question again? | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Grit, meet grot | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Trollbabe: Recensione giocata | Storie di Ruolo