Missed! Ran out! Dang! Unnhh!

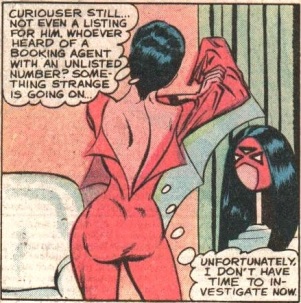

Let’s begin with a serious observation: this is art by Carmine Infantino we’re talking about, and that is a woman’s body for a woman character – no “objectification,” no high heels, no prancing model-on-runway posture. That latter stuff is The Eighties, which in actual chronology were not under way until 1983 and not the standard in comics until about 1987. Spider-Woman provides the perfect lens for the troubled transition between the bad-ass, primal, intelligent, rather animalistic women of the 1970s (see Bless me DC, for I have sinned, Long live lib and Faster, pussycat) and the bizarre Barbies of a decade later – who include, just so I can hear the radiators hissing out there, the fan-fave versions of Rogue and Storm.

Let’s begin with a serious observation: this is art by Carmine Infantino we’re talking about, and that is a woman’s body for a woman character – no “objectification,” no high heels, no prancing model-on-runway posture. That latter stuff is The Eighties, which in actual chronology were not under way until 1983 and not the standard in comics until about 1987. Spider-Woman provides the perfect lens for the troubled transition between the bad-ass, primal, intelligent, rather animalistic women of the 1970s (see Bless me DC, for I have sinned, Long live lib and Faster, pussycat) and the bizarre Barbies of a decade later – who include, just so I can hear the radiators hissing out there, the fan-fave versions of Rogue and Storm.

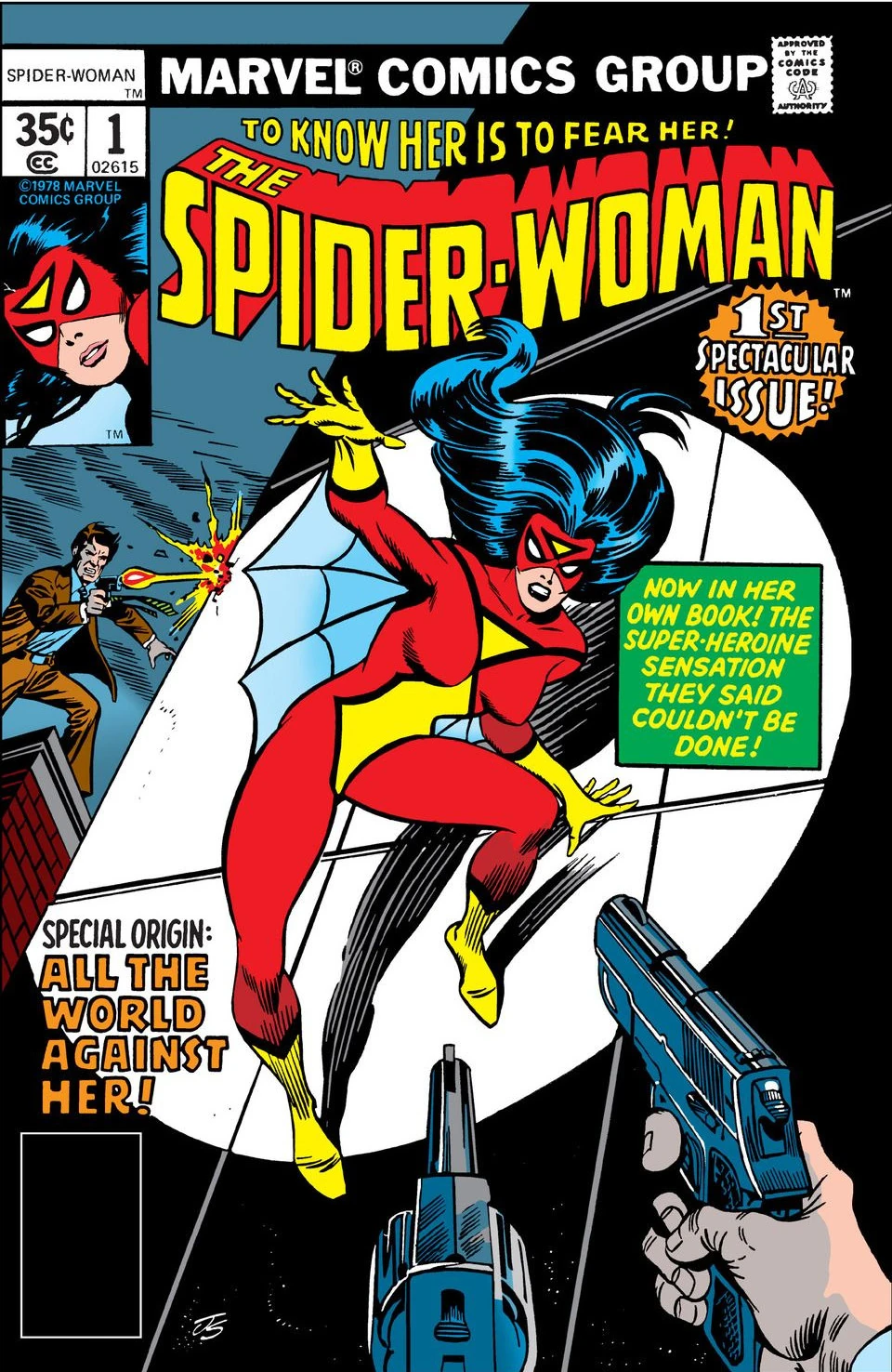

She had her own title for fifty issues, from 1978 to 1983, no small thing. Her start was like many other characters at the time: introduced by Marv Wolfman as the classic “troubled semi-villain” in, in this case, Marvel Spotlight, then cameos in Marvel Two-in-One, in a haze of contradictory explanations and interpretations, and then a finalization regarding powers and personality for her own book. Also, along with the Black Cat, she represents a fill-in for the void left behind when the Black Widow was rendered too tame. The end of the run wasn’t due to crap sales or anything like that, but to one of several publisher-editorial assassinations during Jim Shooter’s tenure as editor-in-chief.

She had her own title for fifty issues, from 1978 to 1983, no small thing. Her start was like many other characters at the time: introduced by Marv Wolfman as the classic “troubled semi-villain” in, in this case, Marvel Spotlight, then cameos in Marvel Two-in-One, in a haze of contradictory explanations and interpretations, and then a finalization regarding powers and personality for her own book. Also, along with the Black Cat, she represents a fill-in for the void left behind when the Black Widow was rendered too tame. The end of the run wasn’t due to crap sales or anything like that, but to one of several publisher-editorial assassinations during Jim Shooter’s tenure as editor-in-chief.

Carmine Infantino busted out 19 issues doing this thing. Most of the rest of the run was drawn by Steve Leialoha, so, not talking about amateurs or second-tier here. Now for the writers list which provides the framework for my post topic:

- Wolfman – (it must be said) at his most maundering and wandering, but also with a specific creepy scattershot feel that makes the character stand out, and also distinguishes her from her male namesake

- Mark Gruenwald – the most significant, about which more below

- Michael Fleischer – workmanlike

- J. M. DeMatteis – re-introduces the contemporary world

- Chris Claremont – about which more below, and as a side point, Leialoha shifts from a credible Carmantino imitation to a credible Byrne one

- Ann Nocenti – whom I remember in other titles as an average contributor in general

I’m not doing this as a survey or review. I’m doing it to pinpoint a weird variable that for which this title is almost an inadvertent dissertation. I’m also not claiming that the 70s women were well-written, but rather that their oddness and problematism reflects a genuine struggle or crisis-phase of the culture, not the cheap heat and nigh-malevolent sabotage of the later step. There’s an interplay among competence, sexy, and sinister that I’m interested in not in its most basic, story-reliable fashion, but in how it gets altered through the course of this run.

Gruenwald’s brief stint is the most significant, the big twist if you will. I will be fair: there is nothing wrong with his use of English; Marvel never hired genuinely incompetent wordsmiths until the 90s. The first major content issue is sexuality, specifically the character’s, relative to what I am forced to interpret as the author as an active … participant. He bum-rushes the boyfriend character outta there …

… puts Spider-Woman into a medicated condition relative to her pheromones (I use the term loosely and elbow my biology self in the eye as he tries to talk), and then here come the gals … oh GOD, cover my eyes for that lesbian psychofest fight scene with Nekra … anyway, I’ll let some enterprising M.A. candidate dwell on that and turn to the other major issue.

Abruptly, the character’s plain competence nosedives. Her heretofore top-tier venom blast becomes an itchy little zap which – get this – she can use once and then it takes an hour to recharge. She’s stumbly and gormless and confused all the time, and the fights become simply embarrassing. This is also the writer of the Official Handbook we’re talking about, and thus it’s a defining image far more so than merely a few issues would indicate.

Fleischer’s stint is banal but completely adequate, all about the manipulator staging misunderstanding fights, sort of an in-story stand-in for what the author was enjoined to do at Marvel at the time. He’s quite horrible to the male lead character, poor wheelchair Scotty, who needs a post of his own sometime. Anyway, Fleischer stayed with her incompetence, keeping it in Gruenwald’s mold.

This ongoing limitation to the character’s effectiveness is very different from the heroism issues I wrote about in Superhuman endurance. I’m making the case that the superhero women of the 70s were underwritten but generally competent, whereas the 80s ones are overwritten and incompetent. Competence is a wonderfully fluid variable in superhero comics, including many dials to spin: crippling moral uncertainty, amnesia and twist-revelations about the past, physical fatigue and response to injury, curious vulnerability, to being sneaked up on and drugged/bonked, uncertain and unreliable powers, unexpectedly powerful “how can he withstand that” male foes, and the oldest standby, fight-affecting coincidences. All of these are fine as minor features or occasional nuances; when they provide a steady hum of plot-significant, even plot-defining input, then we’re talking about a character in whom the writer simply doesn’t believe, no matter how much flak the incidental prose throws about how awesome she is.

If I have to suffer, so do you

DeMatteis’ brief run is kind of a delay or blip; it returns to the Wolfman model of the bounty hunting, strikingly weird villains, and at least an understandable limbo of “who am I.” She becomes competent again, or better anyway. There’s also a striking inclusion of grown-up sex although not for SW, starting with her barging in on Scotty as he’s jerking off (seriously – again, oh my eyes!), and at least worth a mention, Marvel’s first out-lesbian incidental character, an unnamed bar patron.

And then Claremont’s year-long run arrives, and man alive is it ever Claremont. Credit where it’s due, the vocabulary, grammar, and general erudition jump up a quantum; I enjoy his usual paragraph captions about this-or-that real-world building or geographical feature that figures in the story; and he does justice to the California coast both geographically and culturally. I won’t even crank about his endless explanations for what’s going on; he’s not alone among comics writers for that. But his idea of the empowered woman never fails to amaze, in two parts.

And then Claremont’s year-long run arrives, and man alive is it ever Claremont. Credit where it’s due, the vocabulary, grammar, and general erudition jump up a quantum; I enjoy his usual paragraph captions about this-or-that real-world building or geographical feature that figures in the story; and he does justice to the California coast both geographically and culturally. I won’t even crank about his endless explanations for what’s going on; he’s not alone among comics writers for that. But his idea of the empowered woman never fails to amaze, in two parts.

The first is right out of the deeply-compromised Ms. Magazine and Gloria Steinem’s uniquely bourgeois notions of liberation – the TV ideal of what it must be like if you don’t really have to work for a living. There’s the hipster crowd in the loft apartment, all the models and theater people having their cocktail party, hanging out and schmoozing and hooking up … it’s kind of cool until you see it’s unrelentingly leisure class, idealizing sincerity and “finding oneself” in the context of astonishing consumer-superficiality.

The second part of Claremont female competence is incredible multipolarity among “I am the mistress of more power than you can imagine!” “My power drains and stuns me!” and “Jeepers my power does not work this time!” It’s superpowers as troubled orgasm, and that’s not snark or sly or even subtext, it’s plain text.

You put these together and there’s the new stealth-incompetent Spider-Woman: hell against goons, accompanied by much text about how good she is in either first or third person, but all the major foes just go “unnhh” and she goes “I hit him with enough to fell a dozen men, how can he still be standing?”, and all the uncertainty/what’s going on centered on mysterious powerful female villains you can stand. With one or two victories thrown in to keep things confused, and enough unconvincing buddy-buddy sisterhood to make you want to hide the knives.

Finally, there’s a full creative team change-up, with Nocenti writing, illustrated by Brian Postman, and to my eyes most significant, Mark Gruenwald replacing Denny O’Neil as editor, for four very average issues culminating in the hero’s editor-mandated death. I see their content as simply winding the title down in reference to that mandate and no real reason to dwell on it.

The prevailing narrative of the depiction of women in comics is backwards. This isn’t an ascent into empowerment from the hell of sexism and objectification. It’s the opposite. The 70s women were empowered, and don’t mix that up with self-actualized or happy – they’re not the same things. They were written with much ambiguity and incompetence and uncertainty [clarification: those terms are directed at the writing] about that power, yes, just as the better male characters were. They raised questions about what an empowered woman would be like or might want, questions which have vanished and even become taboo. Spider-Woman shows me how that process of erasure worked, and I give some credit to the character concept that every so often she struggled against the tide, the fundamentals battling with the plots. No wonder they had to kill her.

Links: Nowhere / No formats (a blog piece on the Gruenwald phase)

Next: Irish rage, Catholic guilt

Posted on April 10, 2016, in Storytalk, Vulgar speculation and tagged Ann Nocenti, Carmine Infantino, Chris Claremont, endurance, J. M. DeMatteis, Mark Gruenwald, Marv Wolfman, Max Fleischer, Michael Fleischer, orgasm, Spider Woman, Steve Leiahola, The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Okay, I will bite. How does Powerless Storm, circa Uncanny #185-224 (a/k/a “The Years James Read These Comics”) qualify as a bizarre Barbie? I will grant you that during Claremont’s entire run Storm never, ever, EVER received a consistent characterization. And at one time was a space-whale.

But Powerless Storm is, I think, one of the more interesting characters of Claremont’s run. (Interesting, not necessarily plausible in the “I can whip anybody” sense.)

LikeLike

A “powerless” character that never missed, never lost, never made a bad decision, never failed to guilt-trip and patronize everyone else, and evinced zip-zero-zilch context or purpose in her chosen new look aside from some vague nonsense. You’ve mentioned before that this character seems or seemed empowered to you, but to this reader it’s Mary Sue all the way.

But I was mainly referring to the heroines’ elongate build and stupid heels (OK sometimes Storm had righteous boots, I grant that), and the fact that in 1987 or whatever it was, mohawks were now upper middle class chic.I will refrain from cranking about all those faux-hawk mullets in the X-Men because y’know that was the thing then; this is about what Storm’s was about, or rather not about. Expensive club punk, baby! Way to rebel!

(time-stamping this carefully because who know what happened after – I stopped reading the X-Men in the 200-teens, or just after the Mutant Massacre)

Related point and specifically to the Barbie term … since [a person close to me] had very recently not died due to anorexia nervosa at that time, I found the She-Hulk’s weird slide from genuinely sexy-hefty muscled to rail-thin pretty disturbing.

LikeLike

Point of fact: Storm’s mohawk is around ’83 or so – well past the “true” days of Punk but still somewhat transgressive to suburbanites like me: I vividly remember an Andy Rooney segment from around that time decrying the fashion. But you’re certainly right that there was zero character context for it; I suspect Paul Neary just wanted a new look.

(Claremont had like 3 or 4 different iterations of Storm, none of them consistent; same with Nightcrawler. Wolverine enjoys a decent, consistent, long-term character development up until the late 80’s when things just go completely bonkers with him. Kitty got some careful attention too. But pity poor Colossus, who was a total dud in 1975 and is a total dud 40 years later.)

But as regards to this particular Storm: you’re right that she’s unbeatable, but what comics character isn’t unbeatable in his or her own mag? Superman wins because he’s a Kryptonian from Kansas; Batman wins because he’s rich and well-trained; Spider-Man wins because he lost in Act I; Storm wins because of, I don’t know, true grit or something. All of these simply being in-fiction justifications for the victory all seasoned readers know is coming. (How much that victory may seem in doubt along the way, and which hard choices must be made to assure it, are what separate great super hero stories from good ones.)

My recollection is that this era’s Storm actually does make a number of shitty decisions. On a purely personal level she’s got Romantic Angst ™ with Forge, a/k/a Doctor Doom Lite, who through ridiculously convoluted logic is to blame for losing her powers. On a team level, she’s lost the ability to contribute the way she used to, so she’s forced to become cunning and ruthless – traits which actually were slowly coming to the fore for a while. On a leadership level, she’s arguably a trainwreck: her inattention to Rachel’s instability leads to a totally unnecessary fight against the Hellfire Club and Nimrod; her neglect of the Morlocks leads them to get Massacre’d; her decision to send the X-Men into the Massacre when they still haven’t recovered from the Hellfire/Nimrod fight results in the incapacitation of Colossus, Nightcrawler, and Shadowcat. She then assembles one of the weirdest team rosters of all time. And decides, “Hey, let’s leave the mansion and go on a road trip, leaving our teenage wards protected only by Magneto against whatever crazy enemies might be trying to track us down.”

It’s true that Storm seldom wrestles with a moral decision, but very few of Claremont’s characters ever do. (Or, I should say, they wrestle with them frequently, but it’s just kayfabe: we all know how it’s gonna come out.)

For me, Storm was an empowered woman mainly in contrast to the other Marvel candidates in the mid-to-late 80’s. She was never saddled with traditional girly roles of the damsel in distress or the love object. She punched far above her weight class, had to win through cunning and guile, and people who arguably were more powerful than her still saw her as an equal. What young kid isn’t going to like that? (Runner up: Roger Stern’s version of the Wasp.)

LikeLike

You’ve brought this perilously close to “this character does not either suck because I like her [or liked those comics then].” That position only leads to MAD. I’m not telling you that you can’t like the character or that you were dumb to like her then. You asked what I meant; answering doesn’t mean I want to duel about it.

My position: as I understand the concept, the essence of Mary Sue is that he or she constantly does stupid and absurd things but is cast as being amazing and wonderful via the responses of everyone else in the fiction, as well as by authorial phrasings and other coded signals to the reader. That’s what “never made a bad decision” means in my reply.

I stress too that Storm in isolation is not my topic, but rather the trend across female characters at the time. She contributes to it in her way like each of them does in her respective way.

LikeLike

Pingback: 70s and 80s, ladies | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: 70s and 80s, ladies | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Carol Danvers spits on your grave | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: More women part 2 | Comics Madness