Read your Bible

Looking here at the Tanakh, or Hebrew Bible, the first section is the Torah, or the Five Books of Moses, or the Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. (The other two sections are Nev’im, or Prophets, and Ketuvim, or Writings.) The Pentateuch’s five books aren’t really five books at all but a mash-up of many documents to “make” five. Its documentarian breakdown is non-controversial:

The Jahwist text (J) and Elohist text (E) were apparently competing narratives associated with the kingdoms of Judah and Israel, squished together later when the regions became themselves a unit. Although it’s easy to tell which is which, the events J and E describe are combined line-for-line so thoroughly that you can call them JE together.

The Jahwist text (J) and Elohist text (E) were apparently competing narratives associated with the kingdoms of Judah and Israel, squished together later when the regions became themselves a unit. Although it’s easy to tell which is which, the events J and E describe are combined line-for-line so thoroughly that you can call them JE together.- The Priestly (P) and Deuteronomist (D) additions are larger-scale interjections and less blended for the most part. The D is probably several authors from various periods.

- The Redactor (R) text is all bits of glue-like prose linking the other parts together, with no distinct single book or section.

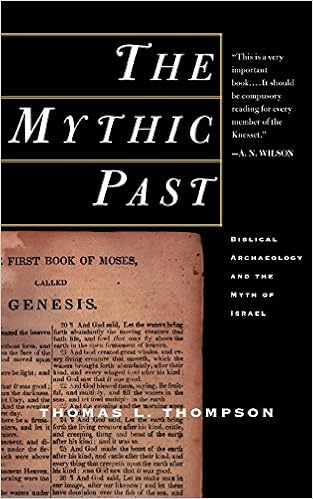

Scholars differ on whether the respective letters represent actual specific “chunks” of document composition or merely identifiable trends in scattered and ongoing composition and inclusion (the fragmentary hypothesis variant). What’s most controversial is the dating: most scholars of this stuff are religious and consistently back-date as far as they can, associating, for instance, content about Moses with the presumed historical time of Moses. My own jaundiced outlook leads me to side with contrarian texts like Thomas Thompson’s The Mythic Past, in which the contributing texts are considerably younger than the dates you’ll currently find at Wikipedia, and the compilation anyone would call a “book” is as recent as 140-37 BCE, i.e., New Testament times, and therefore not particularly ancient relative to it.

Scholars differ on whether the respective letters represent actual specific “chunks” of document composition or merely identifiable trends in scattered and ongoing composition and inclusion (the fragmentary hypothesis variant). What’s most controversial is the dating: most scholars of this stuff are religious and consistently back-date as far as they can, associating, for instance, content about Moses with the presumed historical time of Moses. My own jaundiced outlook leads me to side with contrarian texts like Thomas Thompson’s The Mythic Past, in which the contributing texts are considerably younger than the dates you’ll currently find at Wikipedia, and the compilation anyone would call a “book” is as recent as 140-37 BCE, i.e., New Testament times, and therefore not particularly ancient relative to it.

Therefore the “Bible” in its literal titular meaning, “the Book,” is a physical and institutional artifact far more than it is, or ever was, a “book” in the sense of a text that you actually read. You can see from the documentarian image what a jumble the initial parts are, and my aforementioned jaundiced view is that Genesis was included mainly as an “lookit old stuff” legitimizer for the Priestly contributions in the service of the Maccabeean governing priesthood in alliance with Rome.

I’ll continue with my heresies in suggesting that the internal textual content of pieces like Genesis has been of no religious interest at all except for occasional political cherry-picking, and instead, that “What the Bible says” is at all times an institutional device specific to its own historical period. Such periods include post-Christian Rome (what you probably call “Byzantine”), the Rabbinate during that period, Roman Catholicism (bearing in mind the Vulgate is a later text), the Reformation and its associated wars, and the European 19th century, among others. Modern fundamentalism, although a blip in comparison, looms large in our personal perspective. None of these “what it says” meanings had or has any use for the internal, unabridged textual content, particularly that of the messy and stitched-up Genesis. The content is always universally downplayed and replaced by pedagogical substitutes. (You know this clip, right? Actually, yes, it is a weapon. You’re not supposed to read it.)

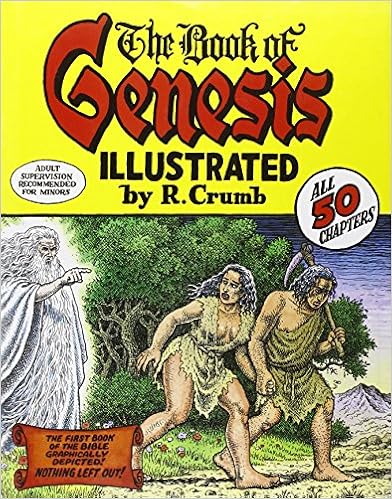

All of which delightfully makes doing Genesis as a comic all the more fun and useful. Reading it outside a “what it means” context (whether to obey or to rebel) is a new experience for just about anyone. Even considering it “a thing” in terms of beginning-and-end is a bit borked, i.e., acknowledging that multiple and layered authorship doesn’t invalidate it as a story, it certainly raises the question of whether it’s a story at all. Therefore putting it into, arguably, the most effective “narrative communications” medium possible, yields something special.

All of which delightfully makes doing Genesis as a comic all the more fun and useful. Reading it outside a “what it means” context (whether to obey or to rebel) is a new experience for just about anyone. Even considering it “a thing” in terms of beginning-and-end is a bit borked, i.e., acknowledging that multiple and layered authorship doesn’t invalidate it as a story, it certainly raises the question of whether it’s a story at all. Therefore putting it into, arguably, the most effective “narrative communications” medium possible, yields something special.

Crumb’s incredible merit bears no discussion – I nod toward it here, briefly, only to say that whatever I say about the art’s effectiveness, go ahead and amplify it astronomically, exponentially. For instance, the detailed humanity in every characterization as he goes, as he a reader, figures they might respond. Every reaction in the moment is apparent, for main, supporting, and incidental characters alike. I’m fond of Joseph’s interpreter, who doesn’t know Joseph understands the Hebrew he’s supposed to be translating for him. Many of these are simply beautiful, and I appreciate that they represent “what Crumb feels people might be feeling” rather than direct text – his interpretations become teachable moments, e.g., how does Isaac react when he realizes why his father brought no sheep for the sacrifice, and how does one’s answer, which might not be Crumb’s, affect the (or rather one’s) meaning for the passage? (For a less favorable analysis, see the Hooded Utilitarian.)

There isn’t any massaging of the text: it’s presented with all its hitches just as is, making duplications and insertions startlingly apparent.

- The duplications are famous, including the doubled origin of the world and mankind, the doubled Flood story, and certain repeats like the three-time “she’s not my wife, she’s my sister” events. Seeing it visually really strikes it home, though – there’s simply no way to cherry-pick lessons about, for instance, female subordination based on Adam’s rib, when the other simultaneous male/female origin is staring you in the face.

- I’m more taken with the obvious snippets of incomplete stories.

- Some of them are practically unknown, like Abrahams’ second marriage to Keturah and their passel o’kids who are never mentioned again, or what appears to be the start of a whole new soap opera when Reuben sleeps with Israel/Jacob’s (his father’s) concubine, which is curtailed just as it heats up.

- Others are long-ago massaged into institutional use, like Cain and Abel, and the fate of Onan, but seen here in readable entirety, demonstrate just how insubstantial the institutional use is. Cain doesn’t seem like a bad guy and his lineage culminates in a completely unexplained event, never mentioned again. The latter story isn’t about masturbation at all, but rather about Tamar tricking her father-in-law into marriage.

I am especially impressed by the richness of stuff that’s otherwise passed over in textual reading. The begats are actually interesting, and since the place-names are mapped, you can see the point of including them as it’s all about what group of people has gone to colonize what region. I’m not too interested in it as actual-history so much as what the textual contributor of this material wanted to institute as history, i.e., probably working backwards through known lineages to hook them together in the beginning.

I am especially impressed by the richness of stuff that’s otherwise passed over in textual reading. The begats are actually interesting, and since the place-names are mapped, you can see the point of including them as it’s all about what group of people has gone to colonize what region. I’m not too interested in it as actual-history so much as what the textual contributor of this material wanted to institute as history, i.e., probably working backwards through known lineages to hook them together in the beginning.

What about the parts that aren’t fragments and obvious interjections? Even given the somewhat-contradictory duplications, is there a story here? Maybe. It’s definitely not a “novel,” especially in isolation from the rest of the Pentateuch. And what’s there, perhaps best described as a family saga, it makes most sense when considered entirely out of context of the retroactive Abrahamic tradition.

That latter statement probably seems ridiculous – is it not a story of a lineage and its sequential encounters with God? The trouble is with how various and weird God is. For one thing, forget monotheism – there are obviously lots of characters which have been potato-mashed into a retroactive fantasy thereof. You have Eloi, Elohim (yes, plural thereof), YHWH (Yahweh), El Haddai, and more, who have grossly obviously different priorities, with no indication at all that these are the same character except that the Redactor author(s) say so. In this case, Crumb’s depiction downplays the diversity of the divine characters and voices, as it reinforces a single-character reading. But for my part, I’m gonna say there’s no way to read this and to take “God” as a throughline active agent particularly seriously, as opposed to reading what’s there and seeing a whole boatload of rather standard mythological agents ranging from grand to mischievous to deranged. In that context, the story isn’t what (the) God wants or even what God is about, but rather, what people do when they feel helpless before a supernatural being/agent’s will, or maybe that they reach for such a will when they feel helpless before other things, and one another.

That latter statement probably seems ridiculous – is it not a story of a lineage and its sequential encounters with God? The trouble is with how various and weird God is. For one thing, forget monotheism – there are obviously lots of characters which have been potato-mashed into a retroactive fantasy thereof. You have Eloi, Elohim (yes, plural thereof), YHWH (Yahweh), El Haddai, and more, who have grossly obviously different priorities, with no indication at all that these are the same character except that the Redactor author(s) say so. In this case, Crumb’s depiction downplays the diversity of the divine characters and voices, as it reinforces a single-character reading. But for my part, I’m gonna say there’s no way to read this and to take “God” as a throughline active agent particularly seriously, as opposed to reading what’s there and seeing a whole boatload of rather standard mythological agents ranging from grand to mischievous to deranged. In that context, the story isn’t what (the) God wants or even what God is about, but rather, what people do when they feel helpless before a supernatural being/agent’s will, or maybe that they reach for such a will when they feel helpless before other things, and one another.

Furthermore, I’ve found throughout my life that when people say “Genesis,” even very religious “I read my Bible” people, they pretty much mean the first ten chapters. 1-3 is origins, i.e., Adam and Eve; 4 is Cain, which is fragmentary and unfinished; 5-ish -10 is a mash-up of apocalyptic fantastic stuff, like the Flood, the Tower of Babel, and the Nephilim, with the first doubled and beefed up by multiple authors (however, not enough to make Noah interesting), and the latter two in very fragmentary form. When people know even these few, they always reference only highly selected and specific bits, adding the Abraham-Isaac sacrifice, cherry-picked from a few chapters later.

But they know little if anything of the rest, which is more than three-quarters of it, in which the events and “plot” sometimes include God stuff , but, especially after the commanded sacrifice of Isaac, are mostly plain-and-pure people stuff who make decisions in moments of family crisis. I’m talking about the throughlines of Abraham’s later life, which is to say Sarah and Hagar; Isaac, which is to say Rebekah; Jacob/Israel, which is say Leah and Rachel; and Joseph. A lot of it is dramatic but more intriguing or disturbing than uplifting or instructive. Some of the characters are plain shitty, and some are weak, and the outcomes don’t really have much “see, God was on your side, your faith paid off” weight. The repeated conflicts are non-abstract, harsh situations, concerning status and hostility between siblings; the exigencies of having to travel to live; fear of a local ruler regarding one’s wife; maneuverings of women regarding marriage and fertility especially concerning barrenness; and periodic famine.

Jacob/Israel’s life is told most completely, detailed in separate conflicts through all phases, albeit muddled through duplicated passages with different details. For the guy who gets this much attention, arguably the “main character,” he’s also the least likeable of the bunch: consistently hesitant, fearful, deceitful, conciliatory to a fault, pushed-around, and passive-aggressive.

- He has brother/mother problems, but it’s weird – there isn’t an evident problem but Jacob keeps acting as if there is.

- There’s a fragmentary bit about a stew; there’s tricking the dying father to cheat Esau out of his blessing, which is really inheritance, with the mother’s help; however, there’s no indication that Esau dislikes him or is intrinsically in conflict with him.

- When they’re reunited late in life, Esau welcomes him back and is puzzled at Jacob’s elaborate attempts to avoid being assassinated or robbed by him; when their combined households are too much for the land, it’s Esau who packs up and leaves, with no evident resentment.

- He has fiancee problems

- Yet in fulfilling his father’s injunction to marry inside the clan, finding the right person is really easy given how complicated his scheme is for doing so.

- It goes south when he gets tricked into marrying the sister instead, and (to summarize) ends up doing a couple decades’ labor and management for his father-in-law in order to marry both.

- There’s a long story about how he gets his revenge on the father-in-law, who doesn’t seem like that bad a guy, basically impoverishing him, including one of the wives pulling what seems to be a pretty low theft.

- He has wife problems, some of which seem recycled/duplicated from Isaac and Rebekah, like the wife/concubine competition.

- Given four (4) mothers of a whole bushel of children, he has kid problems.

- One of his daughters is raped by a local chieftain’s son, which he tries to reconcile by having all of them converted to the covenant – but then two of his sons massacre the town and pillage all the loot and women there. (It’s real hard to find the right or good or sympathetic anywhere in this bit.)

- One of his sons, Laban, has an “evil” son who’s killed, assailants unknown, then that one’s wife has to marry the next son, who doesn’t like her and gets killed, assailants unknown; then she tricks Laban into having sex with her and marrying her. (ditto!)

- There’s a bit which begins an obviously lost story about his eldest son sleeping with his concubine.

- And the beginning of another story about ambiguously first/second twins born to yet another wife.

- All of which takes second place to the problems concerning his only children by the wife he actually loves: Joseph and Benjamin – keep in mind, this is the biggest story in Genesis by far, 13 chapters out of 50 (37, 39-50).

- Here, he undergoes considerable grief and fear with a last-minute save that’s none of his doing.

- Then there’s the out-of-context weirdness:

- The isolated wrestling match with the whatever-it-is guy.

- All of his “God” stuff looks very interjected, having no plot-value or point in any of the situations.

- And that whole thing about setting up pillars everywhere – unexplained, nothing to do with God’s apparent thing for burnt offerings.

I’m a bit disappointed in my webcrawling to discover that commentators go on and on about Crumb’s raunch, as if he’d ramped it up in some text-inappropriate way, when, well, the source material is unabashed raunchy stuff. I actually think he downplays it considerably. There is a whole lot of sex in there, most of it explicitly lacking in virtue by the standards of any/every culture. A lot of it concerns women making sure they conceive in some advantageous way, whether by tricking high-status men, or competing with low-status concubines, or colluding with a husband or lover against their father. Getting your dad drunk to have sex with him, bed-trick switches on your husband who thinks he’s marrying your sister … it makes The Canterbury Tales look PG, and even in text-only form I have to squint to remind myself it’s not some racist tract about degenerate hillbillies. Like I said, I think Crumb keeps it remarkably clean.

I’m a bit disappointed in my webcrawling to discover that commentators go on and on about Crumb’s raunch, as if he’d ramped it up in some text-inappropriate way, when, well, the source material is unabashed raunchy stuff. I actually think he downplays it considerably. There is a whole lot of sex in there, most of it explicitly lacking in virtue by the standards of any/every culture. A lot of it concerns women making sure they conceive in some advantageous way, whether by tricking high-status men, or competing with low-status concubines, or colluding with a husband or lover against their father. Getting your dad drunk to have sex with him, bed-trick switches on your husband who thinks he’s marrying your sister … it makes The Canterbury Tales look PG, and even in text-only form I have to squint to remind myself it’s not some racist tract about degenerate hillbillies. Like I said, I think Crumb keeps it remarkably clean.

My completely selfish view, ridiculous of course, is that I’d like to see the whole Pentateuch done this way, for the sake of my own and future generations’ reading comprehension if nothing else. At least Genesis is mostly JE, whereas Exodus is such an obvious P-compromised text – and in my opinion a rather vicious and negative one – that I’d like to see what would ensue.

Links: Hammer Museum exhibition of the work, excerpt from my book Shahida if you’re interested in my take on holy books, A serious romp through Graf-Wellhausen-Friedman documentary hypothesis

Next comics: August 30, Sword of God, The Edge p. 6; September 1, One Plus One, I Want In p. 9

Next column: Four-color Christ (September 4)

Posted on August 28, 2016, in Storytalk and tagged Bible, documentarian hypothesis, Pentateuch, religion, Robert Crumb, The Book of Genesis, The Mythic Past, Thomas Thompson. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

My reaction to the idea of the Bible as literature has usually been “maybe not-so-great literature,” but I can see where the comic treatment might bump that up a few notches.

And I’ve been exposed to the idea of the Bible as literature in so many ways for so much of my life that it’s hard to take “you’re not supposed to read it” seriously – except, of course, I’ve also met people who clearly cared more about weapon-use than reading, so …

LikeLike

Speaking strictly only from my own experience, discussing “the Bible as literature” is usually predicated on limited ideas. Either it’s the usual “what did the real writer(s) mean,” or it’s tarred strongly with the idea that this tradition somehow invented phenomena like social contracts and ethics. The former is especially complex, because the fixed notion that “this is really important!” is still hiding in there – much like the way people think that finding “the real Jesus” would tell us something important about Christianity. The latter idea is embedded so deeply in general education and culture that I despair of discussing it – you run across it in the fundamental assertions that Babylonian, Persian, Egyptian cultures were all stupid grunting “primitive” civilizations (except for the claimed lily-white Macedonians of course), and before anyone reading this says “but no one thinks that,” I would caution you to reflect briefly on current international matters.

As for the relative presence of “it’s a book, of course you read it like a book” vs. “it’s not just a weapon, it’s the weapon,” I’ll just leave this here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trijicon_biblical_verses_controversy

LikeLike

Yeah, I guess it’s not surprising that my personal, shallowly considered (to the extent I’ve considered it at all) impression isn’t definitive. I just remember 70’s/very early 80’s High School/undergraduate courses on the Bible as literature, discussing things like Mithraism and the “theme” of rebirth. Some controversy, since there were folks who think it’s just WRONG to treat a Holy Book that way, but those folks lost the argument, right? Well, maybe not in popular culture – but in academia, they lost. At least I guess I assumed/HOPED they lost.

But apart from wondering “what people thought/think”, I’ll stress that it’s real easy for me to see how Crumb’s work could boost the literature value/accessibility.

LikeLike

Pingback: Four-color Christ Jesus | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: God, an aardvark, and the man in between | Doctor Xaos comics madness