Spider-Schlep

Posted by Ron Edwards

In one of the letter columns in the late-80s Question, Denny O’Neil refers to Peter Parker as a schlep, and always having been one. That’s Yiddish, and a little confusing because that precise word is a verb meaning to lug something inconvenient, but here, and as I’ve often heard or used it, it’s short for schlepper, meaning an inept, stupid person.

In one of the letter columns in the late-80s Question, Denny O’Neil refers to Peter Parker as a schlep, and always having been one. That’s Yiddish, and a little confusing because that precise word is a verb meaning to lug something inconvenient, but here, and as I’ve often heard or used it, it’s short for schlepper, meaning an inept, stupid person.

As I sat on my studio-apartment futon on the floor almost thirty years ago, on the one hand I was indignant to read that and on the other I knew what he meant. It comes right out of the period from the decade before that, which I think of as Spidey’s Dork Age after the scrambled transition out of Lee’s 100-ish run on the series.

In The Amazing Spider-Man, I’m talking about the Gerry Conway run from 1972 to 1975, followed by the Len Wein run from 1975 to 1978. It’s joined by Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man in 1976 under Conway and later Bill Mantlo, and paralleled the whole time by the curious title Marvel Team-Up, written mostly by Mantlo. A couple of nuances are added by the long-running Marvel Tales, which at this time ran reprints of The Amazing Spider-Man which could be confusing when perusing the spinner rack, and for younger readers, the show-and-comic Spidey Super Stories. Here:

If the Lee run (first with Ditko, then with Romita) was Spider-Man’s literary, even revolutionary identity, as I think it was, then this period’s comics and other media established Spider-Man’s cultural identity. What “everyone knows” the character is. And the news is not good. The main Marvel titles were blighted by the “illusion of change,” and Spider-Man was hit particularly hard.

If the Lee run (first with Ditko, then with Romita) was Spider-Man’s literary, even revolutionary identity, as I think it was, then this period’s comics and other media established Spider-Man’s cultural identity. What “everyone knows” the character is. And the news is not good. The main Marvel titles were blighted by the “illusion of change,” and Spider-Man was hit particularly hard.

I can just hear the cries of woe out there – I’m pissing on your childhood, waaaah. But! This is my childhood we’re talking about. I bought these issues quarter by quarter, haunting the spinner racks. Work with me and, just like I have to, put aside the mythology that the Spider-man saga is defined by the origin (AAF 15), the personalizing of the Green Goblin (ASM 39-40), and the death of Gwen Stacy (ASM 121-122). Think instead in writer, artist, and editor chunks regarding three series titles.

The “main book”

Gerry Conway was not even twenty when he took over The Amazing Spider-Man, representing a thirty-year drop in author age. Although Roy Thomas seems to have mentored him sincerely, Thomas was not in the chief editorship for long, so this young guy was in many ways sent not just into the deep end, but off a cliff (on the Fantastic Four as well, and other main titles to come). I want to stress too that Conway was a superior prose artist – perhaps the first really skilled producer of human dialogue in superhero comics without injecting comedy or working within the conventions. Better even than Steve Gerber, more disciplined and in-character. It’s important to my points.

There’s no nice way to say it: his Spidey/Peter isn’t schleppy, he’s a real asshole – sulking, spiteful, randomly hostile, and passive-aggressive. The long list of lying to, snarling at, dismissing, and generally badly treating his friends through the run is jaw-dropping, incredible. It’s captured perfectly in two pages from #129. I’ve remembered the sequence for all these years because it was genuinely disturbing, and it’s even more so now … just look at him. The silent panels at the page transition literally shout his isolation and his disgust with anyone and everything, trying and failing to put on a shitty-happy face. Then literally sneering at Betty as she tries to connect with him. (Back in #112, Jameson refers to him as hanging around the Bugle “like some kind of growth,” and he has a point.) This guy is more than reluctant or a bit doubtful – he hates being Spider-Man, and only does it because he hates it a tiny bit less than being Peter Parker. It makes perfect sense that his transition into Conway’s tenure is getting diagnosed with an ulcer.

There’s no nice way to say it: his Spidey/Peter isn’t schleppy, he’s a real asshole – sulking, spiteful, randomly hostile, and passive-aggressive. The long list of lying to, snarling at, dismissing, and generally badly treating his friends through the run is jaw-dropping, incredible. It’s captured perfectly in two pages from #129. I’ve remembered the sequence for all these years because it was genuinely disturbing, and it’s even more so now … just look at him. The silent panels at the page transition literally shout his isolation and his disgust with anyone and everything, trying and failing to put on a shitty-happy face. Then literally sneering at Betty as she tries to connect with him. (Back in #112, Jameson refers to him as hanging around the Bugle “like some kind of growth,” and he has a point.) This guy is more than reluctant or a bit doubtful – he hates being Spider-Man, and only does it because he hates it a tiny bit less than being Peter Parker. It makes perfect sense that his transition into Conway’s tenure is getting diagnosed with an ulcer.

In re-reading, it’s compelling as a realistic, meticulous portrait of clinical depression, laid down with force by the aforementioned skill. That stupid Metals interpretation of comics history is yet again easily disproved, as the Conway Parker is as good an example of genuine anti-hero as it gets, much subtler as such, and deeper, than, say, the 1980s Punisher and all his ilk. The downside, no pun intended, is that (i) it obviates the Lee story totally, (ii) it’s no kinda superhero, and (iii) it’s … well, contagious, in the way that you can be drawn in behaviorally by someone else’s pathology.

In re-reading, it’s compelling as a realistic, meticulous portrait of clinical depression, laid down with force by the aforementioned skill. That stupid Metals interpretation of comics history is yet again easily disproved, as the Conway Parker is as good an example of genuine anti-hero as it gets, much subtler as such, and deeper, than, say, the 1980s Punisher and all his ilk. The downside, no pun intended, is that (i) it obviates the Lee story totally, (ii) it’s no kinda superhero, and (iii) it’s … well, contagious, in the way that you can be drawn in behaviorally by someone else’s pathology.

The villains aren’t the half of it. The whole world he’s in, the non-costumed one, is unbelievably horrid. Flip the pages and look at the faces – everyone is angry, breaking down, or oblivious, all the time. Never before in mainstream comics, and never since, have the police been as quick to launch into free-fire on sight. Since this was my childhood reading, I have always been baffled when people mention the Code’s insistence on portraying law enforcement positively, as I had come into comics exactly when they were emphatically not.

The villains aren’t the half of it. The whole world he’s in, the non-costumed one, is unbelievably horrid. Flip the pages and look at the faces – everyone is angry, breaking down, or oblivious, all the time. Never before in mainstream comics, and never since, have the police been as quick to launch into free-fire on sight. Since this was my childhood reading, I have always been baffled when people mention the Code’s insistence on portraying law enforcement positively, as I had come into comics exactly when they were emphatically not.

I’ll give it this: in that mission, it succeeds. The stories start dark and go dark from there. Even aside from Gwen’s death, Harry’s utter disintegration, and Aunt May’s unrelieved estrangement, you gotta hand it to a comic which taught children vocab like “duodenal ulcer,” “total clinical psychosis,” and this charmer from #138:

Yeah, that’s me — Mr. Masochism, 1974! If things go badly, I’m unhappy — and if things go well, I’m unhappy — so either way, I just can’t win.

Understandably, in order for depresso-Peter to look good while unironically referring to slitting his own throat (yes, that’s in #141) or to “crawl under a rock and die” (#146), you have to make the villains berserk brutes, thoroughly unhinged masterminds, and wildly-grinning psychopaths, which all of them are, and poor Goblin-Harry gets to be all three at once. I’ll grant you that Doc Ock as crimeboss vs. Hammerhead isn’t all that bad, and that most of the new villains were solidly in the Lee-Ditko tradition, good and bad. I’m willing to forgive-and-forget the Gibbon, the Kangaroo, and the Grizzly. Maybe the Mindworm, if you are. And two “new shadowy villains” in Dr. Jonas Harrow and the Jackal, who aren’t great, but provide some throughlines. Don’t think being a bad guy keeps you safe though. I’ll let you count how many times villains die in really horrible, tragic ways which are not played for “gee, no one could have survived that” winks.

The first Conway year’s art is by Romita, mostly inking himself, then Kane with Romita’s inking. It’s magnificent, and I think, uniquely super-noir. It has a shadowy, smoky look which stands up with the edgiest rendering in comics even today, the POV works at any zoom or angle, the fights are frankly scary in their brutality, and the expressions and body language contribute greatly to the trapped, edgy psychology. Then Ross Andru begins his five-year run, inked mostly by Frank Giacoia during this phase, and you can join the cacophony of debate about whether that’s good or bad at the website of your choosing. I go back and forth about it. To the point of this post, though, Andru’s New York locations were in flawless perspective and incredibly detailed; it’s all easy to “feel” as a naturalistic environment.

Can you see what I mean about the illusion of change being both too much and not enough? Killings galore, villainous revision of the supporting cast, killing and cloning the female romantic lead, cloning the hero with a full unresolved “which is it,” a substantial new rogues’ gallery … Never before had there been this much unrelieved change! And yet there’s no change in story. Lee’s 100-ish issues move with verve through distinct stages of maturity, strength, and romance, but here, the Swing has become the Drop. Peter remains the same throughout: sulking, sullen, smirking, with flashes of sudden rage, and more important, his circumstances remain stuck in a grim, even nasty interpretation of the Lee-Romita period. Even starting up with Mary Jane is a stunningly cruel set-up for clone Gwen’s return. As Spider-Man, he swings around a lot, gets shot at a lot, and hits a lot of costumed people, but doesn’t do anything, socially speaking, and his troubles with reputation hit a low point and then stay, and stay, and stay there.

Wein takes over at the #151 mark … and holy shit, I’m now realizing that this whole period presents the perfect contrast between the worst of Marvel in a Marvel book and the worst of DC in a Marvel book. I know that’s really harsh, but stick with it for a second. The worst of Marvel is misery porn and bathos, that’s easy; whereas the worst of DC is slavery to the screen – TV episodes at most, more often nothing but trailers, striving for the utterly average.

Don’t think I mean it lightens up. It doesn’t. #151 opens with Spider-Man disposing of a body in a city dump incinerator, and to add to that, it’s his “own” body (his clone’s), eulogizing with:

Sleep well, fella. At least your worries are over! Who knows? Of the two of us, maybe you’re the lucky one!

If anything, the title gets even harsher. Stories either begin or end with an innocent person’s dead body. Wein was hell on wheels when it came to writing plain mean people; I clearly recall my own age-ten reaction to #153, when the goon grabs a sparrow and then crushes it to death on-panel to emphasize his threat. The police remain outright murderous. Peter is all the more turned into an ongoing repetition of grinding, inescapable woe and personal failure, with all social maturation (college, real employment) abandoned. The social/soap material turns the supporting cast into a bunch of off-putting nonentities (MJ is a flighty, bad-tempered witch, Flash is an ineffectual everyman who says “huh?” a lot, Harry is horrifyingly neurologically damaged), and hits a level of cycling sameness practically at Archie level, if Archie were set in Sartre’s Hell. It makes the continuing expansion of young readers’ vocab, e.g., “sex fiend,” almost funny by comparison.

Wein’s crime-drama murder-puzzle plots are individually excellent, another hallmark of DC training, including the way that you can slot any hero into the lead role. But his super-foe stories are terrible, by the numbers, all introduced, fought, and finished like clockwork. Conway’s interesting politics are gone; there are no politics. There’s an endless parade of “gallery” villains: the Molten Man, the Shocker, the Kingpin, the Tinkerer, the Lizard, Spider-Slayer bots, Silvermane (!), all of whom were specific to stages of Lee’s character development but reappear now as commodities, none more so than the Ock-Hammerhead retreading. Along with a few one-shot-and-drop crooks like Mirage, Jigsaw, and Photon, there’s also a real salad of odd, completely unhinged villains like Stegron, Will-of-the-Wisp, Doctor Faustus, and that Bart yahoo who tries to be the Goblin, who seem always to be about 75% baked in terms of concept and imply that Len Wein really does not like scientists and psychiatrists. After about a year, the hero crossovers begin as well, equally programmed with their interminable misunderstanding-fights.

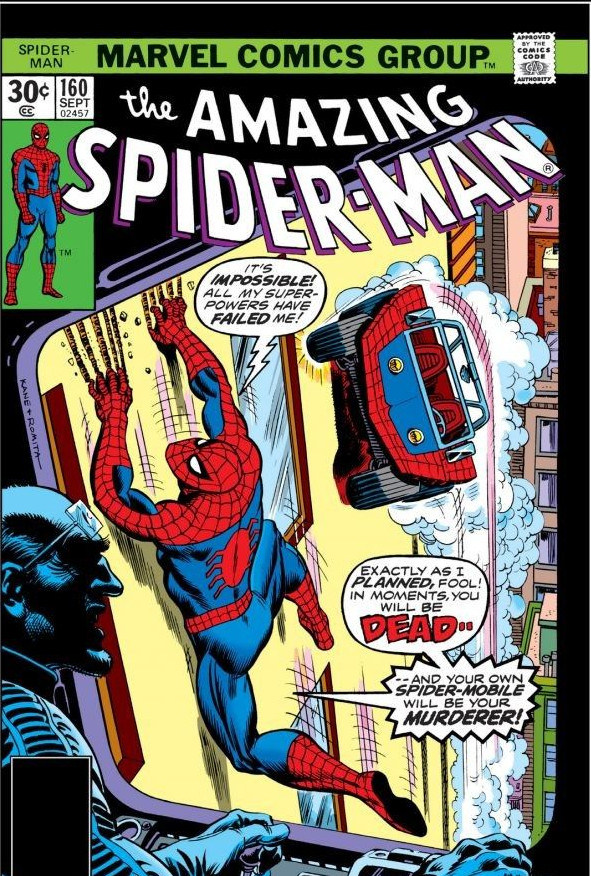

One side point: it strikes me that the Wein run is kinda racist, in contrast with previous Spider-Man stories. Aside from introducing the interesting and lovely Glory Grant, who then does literally nothing, black characters include “snarling like animals” (that’s a caption quote) as well as whatever you want to call Toy from #160 (I remember being upset by that at eleven!). I also under-brow stare at the bland portrayal of Robbie Robertson and at Randy’s single silent cameo. That said, his final few months on the title are much better in this and all other respects, with more characters saying and doing more sympathetic things, a little bit of spine for Harry, and even a little zest for Aunt May.

Mike Esposito began inking Andru just before the author transition to Wein, but he isn’t as consistently present as I’d mis-remembered. Romita continued to provide inks sometimes and the last year of this period is with Jim Mooney using a Romita-like style.

The more I think about it, the more Miller and Janson’s Daredevil owes to this run than he does to Batman in any form – you might forget that it began at about this time; it wasn’t an “80s” book. The swathes and patterns of black are all there already in Romita over Andru, inarguably providing a master class for the ambitious newcomers. Plot-wise, DD also shows what you can do with the depresso-hero when you’re in cahoots with your editor, when you have a real villain, and when, since you’re on a perceived secondary title, the plots are allowed actually to get somewhere. Some enterprising literary analyst may some day explain to us whether that run’s similarly ham-handed and doomed friends-and-lovers soap, including the girlfriend murder-by-villain, and by far the weakest component of Miller’s DD run, came from this specific sequence of Spider-Man as well.

I say again, and again, that none of this was garbage at any level. Like Conway, Wein was indisputably good at the fundamentals and details of pacing and dialogue. But that fact makes it all the more terrible – you get tons of material for actual plot to occur, with intelligent and engaging characterizations that lead you to think the characters will produce one, and yet it keeps slamming back to baseline, to create a hellish existence for protagonist and reader that would horrify even Charlie Brown. It also wigs me out a little that somehow, given their differences in structure/style, each writer contributed to exactly the same readable-but-unreadable hamster-wheel effect.

Peter Parker

You’d think the launch of Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man in 1976 would be a chance for the recovery of a hero without a personality disorder. The theory was that the main book would lean toward slam-bang action and this would lean more toward the socializing and Peter’s general life as a guy, while remaining in continuity with one another, but something else happened.

I bought this title to #20, as best as I can tell, which roughly corresponds to Wein’s run on ASM, but I’m not going to run through it in similar detail. I don’t have fond memories – it was the real beginning of my realization of how much money they were making off me because I wanted it to be good. In re-reading, I find that the only thing I really like are the occasional knockout covers, featuring Marie Severin, Dave Cockrum, and more.

Now, aided by my Context! post, it’s time to explain how the whole writer narrative I’m delivering here is actually a by-blow of the larger editor one. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story explains in detail the intense pressures both Conway and Wein were under as Marvel ownership fell into the hands of Shelly Feinberg and Al Landau, including health problems as well as their complex feud over the chief editorship. My outline draws on that to focus on the structure of who held what position vis-a-vis Spider-Man.

- Thomas steps down from the chief editorship in 1974

- Conway was possibly groomed for this position during the period when he becomes writer on ASM

- Wein becomes chief editor and specifically the ASM editor with #142

- Wein and Wolfman had been elevated to the chief editorships (color and B/W respectively) very much to clean house and to establish a more DC-like structure

- Wein takes on writing ASM with #151 with the text implying a struggle for control of content

- Peter Parker is launched at about that point

- Several writers pinch-hit through its first year including Conway

- Mantlo thereafter

- Wolfman becomes ASM editor and ASM writer with #182

Bluntly, the Wein-Conway transition is clearly not smooth and concerns much more than merely who’s writing a single title. The clone story is written under duress (“Bring her back!”) and may well be a fuck-you to shove the book into a corner, as well as being uncharacteristically careless on details. Goodwin and Kane do #150 as an obvious quick-fix fill-in to redial the who’s-a-clone thing, and #153 includes a whole editorial page fakesplaining all the holes in the Jackal story as due to “space constraints.” It’s pretty easy to contrast with the later transition to Wolfman which, barring the fill-in of #181, is from Wein as writer-editor to Wolfman as writer-editor. The latter two were lifelong friends and professional allies who’d pretty much shared their editorships anyway.

But all that leads to a much funkier picture for Peter Parker, in which the mess is evident via the writing roster: Conway on #1-2, Jim Shooter on #3, Archie Goodwin on #4-5, Conway on #6, Goodwin on #7-8, Mantlo on #9-10, Claremont on #11, and then all Mantlo after that with occasional fill-ins by whoever. Clearly no one was initially conceived as or trusted with actually authoring the thing. This is under Archie Goodwin’s chief editorship, who according to Marvel Comics: The Untold Story is making sure Conway is getting work, but he doesn’t stay on it – perhaps not inclined to continue to coordinate with Wein and Wolfman, I can’t say.

The art, too: instead of getting a specific artist to provide it with identity, it becomes one comic across two titles – whereas ASM has Andru with Buscema pinch-hitting for deadlines, this has Buscema with Andru pinch-hitting for deadlines. I get the impression they wanted two Spidey titles at the customer price-point while paying for one artist and one pinch-hitter, rather than for two artists.

It’s pretty clear that no one writing cared much: it practically codifies Spider-Man boilerplate, with an even more undramatic rogues’ gallery revolving door than in ASM: Kraven, the Vulture, the Beetle, Morbius), and with Mantlo, a bevy of absolute jobbers like Razorback, Brother Power, Sister Sun, and Lightmaster. As for the alleged personal drama, if the names Hector Ayala and Sha Shan make you clutch your head and groan, then this is what you’re remembering.

It’s painfully evident that these aren’t stories, but cycling characters through publication either for try-out or to maintain copyright or just to keep the damn pages filled up. It isn’t another Spider-Man comic, instead it spreads the same one across 44 pages a month instead of 22, bulking up the “is” with the reading equivalent of packing peanuts. If the Wein Spider-Man may be considered the beta Lee (as initiated by Conway), then PPSM is beta beta.

However, its own internal quality is only a means to an end. First, there’s a lot more of this sort of Spidey (who he “is”), and second, it generates an inter-connectedness among purchases on the purported strength of this “is.” It is exactly when attention to continuity became a selling point, so that you had to cut back and forth (or they said you “had to”), which rapidly expanded to other titles, especially sagging ones like The Champions.

Team-Up

By contrast, and completely counter-intuitively, the Spider-Man reader’s-end was held up throughout the entire period in the unlikely title Marvel Team-Up. This is really where I went for my Spidey; the pile I inherited from my brother began with #3, and I started buying them myself somewhere in the late #20s or early #30s.

By contrast, and completely counter-intuitively, the Spider-Man reader’s-end was held up throughout the entire period in the unlikely title Marvel Team-Up. This is really where I went for my Spidey; the pile I inherited from my brother began with #3, and I started buying them myself somewhere in the late #20s or early #30s.

I can understand if you don’t believe me. Obviously the title’s content is absurdly constrained by [buddy of the week] + [foe of the week], thus wasting pages on contrivances. However, the Team-Up Spider-Man is much more likeable as a spunky and often victorious hero, and counterintuitively, being forced to fill pages with the above two contrivances cuts way down on the gross soap opera. There’s still a lot of Peter but mainly in glimpses of the normal course of his day, not getting kicked in the teeth constantly.

Here’s the weird thing: starting with #2, Conway writes the first year – then Wein writes the second – and Conway writes the third – after which it’s Mantlo’s title for the foreseeable future. These shifts correspond weirdly with the drama enveloping the main title:

- Conway’s first year on Team-Up corresponds with his first year on Spider-Man

- Wein’s year on Team-Up corresponds with his editorship over Conway on Spider-Man

- When Wein takes over Spider-Man, Conway gets another year on Team-Up while only occasionally pinch-hitting in Peter Parker‘s first year

Here’s the weird thing about the weird thing: the text shows no evidence of the rancor or hassles between Conway and Wein, and (gasp) it even looks like these two stressed-out, cranky negativists are having fun. The plots are strangely less laborious than in the parallel situation of guest spots in the “real” titles. All three main writers were good at taking over highly creator-specific characters like the Ghost Rider so the characterizations come off as homages rather than chores. Spidey’s opinion of each guest star is genuinely distinctive, even thought-provoking.

The villains are also surprisingly entertaining, perhaps because they figured “there is no top” and could bring in forgotten guys and write’em with a 1960s level of audacity: Kryllk! Zarrko the Tomorrow Man! Moondark! Catman, Ape-Man, and that other guy! This is also where some of the stranger villains come from, who seem to exist only because they’re fun to draw, like Equinox. The art is mostly Kane or Sal Buscema, the latter getting especially well-paired with Steve Leialoha. And things sometimes get trippy, which is sadly lacking throughout most Spider-Man work.

Mantlo’s #41-46 blew my mind: a time-travel trip-out beginning with the Vision and the Scarlet Witch, then the sole villain-team-up issue with Doctor Doom, then jumping to Killraven and Deathlok, wait, and Moondragon was in there somewhere too. Sound stupid? It’s a sustained weird and scary reflection on war and bigotry, with a lot of striking content, including on-panel mass hangings in Salem, a jaunt to Killraven’s hell-future a few decades hence, and a similar one to Deathlok’s in much-nearer 1990. This was Mantlo’s “Scream” period, which I admire, and sure enough, Wood-God did show up in #53-54, although (and here I suspect the hand of Shooter) he didn’t get billed as the team-up partner. I think those were my final issues.

Mantlo’s #41-46 blew my mind: a time-travel trip-out beginning with the Vision and the Scarlet Witch, then the sole villain-team-up issue with Doctor Doom, then jumping to Killraven and Deathlok, wait, and Moondragon was in there somewhere too. Sound stupid? It’s a sustained weird and scary reflection on war and bigotry, with a lot of striking content, including on-panel mass hangings in Salem, a jaunt to Killraven’s hell-future a few decades hence, and a similar one to Deathlok’s in much-nearer 1990. This was Mantlo’s “Scream” period, which I admire, and sure enough, Wood-God did show up in #53-54, although (and here I suspect the hand of Shooter) he didn’t get billed as the team-up partner. I think those were my final issues.

Merchandising

Wham, right at this time, I’d say 1975, the huge licensing and toy endeavor descended like an invasion of the Killraven alien horde. I was a big fan of the Mego figures, this is true, and one friend of mine, recently re-contacted, can’t stop talking about the stop-motion movies we made with the Goblin and Spidey re-enacting #122, so I wasn’t alone. The other toy-type stuff like kites or whatever was unbelievably horrid, cheap nasty junk, but there was a lot of it. TV got into it, first with two seasons of Spidey Super Stories skits on The Electric Company, accompanied by the little-kids comic which would run for quite a while, and then the much-promoted two-season TV show. That latter, counter to fandom’s ever-mistaken memory, did well in the ratings and didn’t fail, it was shitcanned by the studio. There was also the rock album which I wrote about in Whoa-oh-oh naa, whoa-oh-oh na na. 1970s pre-teens were very hungry for their own generation of product and went nuts on all this stuff.

Which is all well and good when sipping your Slurpee, but if you were reading the comics, this merchandising push was flatly bizarre. Early therein, no one realized its power to overwhelm. Both Conway and Wein could lampoon the infamous ‘Mobile and bring it to more than one nasty end, but the joke turned out to be on them within another year. Who could forget the onset of those full-page Hostess Fruit Pies ads? But I’m not saying this to snark. Let me see if I can make my point about a profoundly mixed message by which I was just old enough and economically savvy enough to be repelled.

First, Spidey is being marketed for the first time as a cultural rival to Superman, festooning t-shirts, lunchboxes, Slurpee cups, TV kids’ skits, the rock album, an endless array of decals, a new prime-time show, and just about anything that wasn’t nailed down. The character is billed as a kid-friendly and uplifting figure with a delightfully spunky smart-mouth and heartfelt “great responsibility” values. He’s now present in the comics as a meta-title, across three series (four if you count Super Stories) which also serve as glue across multiple other series and “floating” characters. The magic word “movie” has been spoken out loud. The fruit pies are significant: co-opting the medium hitherto dominated by Charles Atlas, of comics-as-ad, ad-as-comics.

First, Spidey is being marketed for the first time as a cultural rival to Superman, festooning t-shirts, lunchboxes, Slurpee cups, TV kids’ skits, the rock album, an endless array of decals, a new prime-time show, and just about anything that wasn’t nailed down. The character is billed as a kid-friendly and uplifting figure with a delightfully spunky smart-mouth and heartfelt “great responsibility” values. He’s now present in the comics as a meta-title, across three series (four if you count Super Stories) which also serve as glue across multiple other series and “floating” characters. The magic word “movie” has been spoken out loud. The fruit pies are significant: co-opting the medium hitherto dominated by Charles Atlas, of comics-as-ad, ad-as-comics.

And yet in the still-primary title, he’s absolutely an unhinged depressive with homicidal act-outs, and no, I am not kidding. You read that page! Yeah, this is the guy who’s supposed to be endorsing Hostess Fruit Pies? What’s in ’em, Thorazine? For further uplifting content, that story opened with a narrowly-averted rape and knifing. Mm-mmm, fruit pies!

Looking back

This is a LOT of Spidey, a tsunami of visual presence and products landing right on a generation who did not experience the Lee stories and who only received select pieces of them. I can accept that a comics character who “succeeds” has no choice but to become a cultural version of himself or herself, and also that the fiction must become episodic in terms of first-encounter writing logic and designated rather than organic arcs. But those stories, or as I’ve tried to argue, that novel, was and remains lost.

Recall that at that time, there were few collections or compilations. The origin was told over and over, in The Origin of Marvel Comics or in inserts in kid magazines, as were #39-40. You could find some older stories in the Spectacular specials, and the 1960s issues were reprinted monthly as Marvel Tales, but they were not very easy for a kid on a limited budget to follow and parse. There were no paperback compilations like today’s. No one had amassed dedicated runs of the 1960s issues – my generation was the one that invented owning sequential runs mainly by accident, because we refused to throw them away, and longboxes were a decade away in the future. An incomplete stack of Lee-Romita like the one I inherited from my brother was a real exception; no one knew who Captain Stacy was.

When the onset is so “big” like this, past a practical level of purchase and attention, bigger than the scale that you can yourself manage to take on, you lose critical capacity to read the content in a literate way and instead uptake the perceived gestalt as the “thing.” This 1977-ish “thing” became and is Spider-Man, its spine of origin-Goblin-Gwen literally summarized by Mantlo in ASM #181 (the Wein-Wolfman transition). Not just a Universe “is,” but the whole readership’s – what the producing end of more Spidey-reading would have to take as a given or “it wouldn’t be Spider-Man.” And it’s a weird, mixed-message mess.

It certainly contributed to my abandoning the superheroes in late 1977 or early 1978, as I described in The beginning, Never heard of’em, and The river. Regarding Spider-Man, I might have hung on a bit longer; I recall finally recoiling when Peter dropped out of college. There simply wasn’t any text for me to use any more as “the good, real, core stuff” in the face of the overwhelming franchise-“is.”

I don’t think O’Neil was right about Peter always having been a schlepper, nor do I think he was quite right about these either – but yet, he’s not wrong. The Lee story was, as I’ve written about in detail, an excellent novel with a remarkable, powerful ending, if necessarily diffuse in actual presentation. The Conway/Wein runs are … weird, in that they do not quite internally write Peter as a schlepper, rather to the contrary as a disturbing wreck of a man trapped in hell, but the effect produced by serial fiction is to create a schlepper. In pure literary terms, O’Neil nailed it that the classic existential protagonist cannot be a hero – we’re in L’Etrange and Notes from Underground territory in which the human existence descends into a blend of murder and pathos, unleavened by hope-spots or even black comedy.

It’s bigger than that though. This period locked down the characterization into the culture as a commodity, most obviously in all this kids-targeted image-saturation onto everything,but especially as a reader-capture commercial enterprise regarding the interacting comics themselves. Together they established who Peter/Spidey “is” at the expense of what happened in his story – meaning, at the expense of there being a story. Therefore this protagonist is necessarily trapped into the lying-centered, unfunny soap opera and a parade of villains he cannot truly stop – no arc-conclusion is permitted. Given the naturalistic backdrop which forbids him to escape to the stars like Superman did (and who also benefited from his own lockdown occurring during wartime propaganda, i.e., a winner), and bereft of the parody and satire afforded to Howard the Duck, Spider-Man necessarily becomes inept, stupid, and helpless.

Special trivia: the coloring sometimes made Peter’s eyes blue and sometimes brown, and Mary-Jane liked to call him “[color]-eyes,” which got very confusing month by month. My favorite comics coloring error, however, arrives in #157, when he crashes through a woman’s apartment window with no pants (him, not her). Really, go look it up.

Next comics: Sword of God, Friends, p. 5; One Plus One, Two, p. 8

Next column: Elementary

Posted on November 13, 2016, in Storytalk, The 70s me and tagged Al Landau, Archie Goodwin, Bill Mantlo, Chris Claremont, Daredevil, Dennis O'Neil, Frank Miller, Gerry Conway, Gil Kane, Green Goblin, Gwen Stacy, illusion of change, Jim Mooney, John Romita Sr., Len Wein, Marv Wolfman, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Marvel Team-Up, Mike Esposito, Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man, Ross Andru, Sal Buscema, schlepper, Sheldon Feinberg, Spider-Man, Spidey Super Stories, Steve Leiahola, The Amazing Spider-Man 1977 TV series. Bookmark the permalink. 9 Comments.

Wow. This very much explains why I had the perspective I did on Spidey when I was a teen. I started collecting in 1987, at age 13, and used the Handbook and spending all my allowance on back issues and reprint books to try to get “up to speed.” It worked pretty well with the X-men and somewhat for the Avengers, but both Spiderman and the Fantastic Four seemed too big for too little payoff. I didn’t have the funds to try to drink those oceans. I knew unquestionably that Spiderman was the “main character” of the Marvel universe, but I could never find anything compelling about him. The Handbook laid out what you called “the origin-Goblin-Gwen spine” and then a lot of nothing. I was a sucker for crossovers, and every Spiderman crossover issue seemed the same. I’d browse the back issue bins and pick up issues of Marvel Team Up featuring characters I liked and the Spidey portion felt the same way. Nothing happened. Your comparison to Charlie Brown is apt.

Your cautionary note about how this sorry of thing is inevitable on serial fiction is a bit chilling, as I’m starting some serial fiction of my own.

LikeLike

Hi! It was great to see you last weekend and to get the new version of With Great Power …. I wish the timing had permitted this post to come out beforehand so we could have talked about it.

We are exactly ten years apart in age. But it’s not “just” a given time-unit, which at our ages (52 and 42) means practically nothing, especially not for two people with deeply people-engaged lifestyles and paths filled with hard decisions. There is something about the particular intervening decade that matters. Not, I hasten to add, that makes me more insightful or better-positioned than you – but rather, has unique properties regarding comics and pop culture that I do not think any other intervening ten years would have held.

My post “The River” is part of that, in that my second step into said river was your first step, and so that makes our experiences into an opportunity for comparison. The comparison is potentially more insightful than either of our individual summaries would be.

The Official Handbook is part of it too, which you know I regard as a near crime against humanity. It extends both into the past to replace the actual text and its powerful content with pablum “this is his power” summaries and obvious plot revisions, and into the future as editorial-level authority over what must be repeated and re-establishd about the character henceforward. I’ll go further to say that Gruenwald’s choices in what to codify were bizarre and often gross – e.g., why Hank Pym as an abusive psycho had to be enshrined, as opposed to evaporated just like any number of other more solid plot points were, is beyond me.

Another part is thinking about 2005-2006, when you might recall we could never quite get into the same conversational space about With Great Power …, despite both of us being enthusiastic.

The tricky part for Spider-Man is that my grasp of his 1978-1987 period is poor. I read some or all of it as a chunk once, thirty years ago exactly, and upon seeing McFarlane’s version, decided that needed no further viewing. I didn’t tune into Spider-Man again until the 2003 film. I recall enjoying Stern’s stories a lot, especially with John Romita Jr.’s art – I think of it now like Conway in style (which is a good thing) with a different, positive, if perhaps bland foundation. But that’s not a reliable assessment given the decades; I may have to look them and the preceding Wolfman period over in order to say anything I trust.

My apologies for the perhaps over-intimate reply, but talking about Spider-Man tends to bring out the TMI in people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not TMI, just a busy couple days. It was great to see you at Metatopia, even if just for a bit. Dreamation is in February. I’m just sayin’.

As a teenager without any older friends or relatives to bequeath me stacks of comics (which is an origin story I’ve heard from more than just you), I felt at the time that the Official Handbooks were a way to get at that vast, rich trove of backstory that was affordable and accessible. I read every entry. I cross-referenced characters. It gave me a sense of what the characters were “about”, although that sense was often shallow and warped.

My most shame-faced confession born from that sort of reading is that I didn’t really understand that Jean Grey coming back from the dead was a retcon. Even after I knew what had happened on an intellectual level, it took me a decade or more to really begin to understand what the impact must have been on the current readership.

When I was publishing the classic edition of With Great Power, I was still working my way through that belief that I knew so much about comics that I had never read. And now that I’ve got the access through Marvel Digital, I have so many competing demands on my time.

Plus, to be honest, I find the stylistic conventions of the 60s stuff (Lee and Thomas, in particular) difficult to read. I forced myself to read the Kree-Skrull War recently and was so put off by the tin-eared dialogue (“Show ’em, High-Pockets!”) and the strange status quo (Why is Clint Barton currently Giant-Man? What does that have to do with his criminal past or anything else about the character? Why should I care that he sacrifices it for the greater good?) that I actually had to stop myself after each issue and process the amazing ideas that had been tossed out. And remind myself that this was the debut of those ideas.

That’s the other catch. You can only have your first exposure to something once. The Official Handbook spoiled so many reveals for me that I can never get back. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from it, it’s to be attentive to what spoiler warnings I ignore, and try to be respectful of others’ spoilers. Stories are power, but they are a fragile power.

I’ve also typed too much and not enough. Gotta get to work.

LikeLike

Maybe I’ve got substantive comments about me & Spiderman in the context(s) of this awesome post, but it just won’t quite materialize. But at the core of those theoretical-comments is my formative Spiderman experience, the 1967-70 (and, it least in my six channel – SIX!, double the normal three! – NYC-area TV broadcast area, endlessly repeated for years on Saturday mornings) cartoons. My casual research reveals Ralph Bakshi was deeply involved in seasons 2/3. His trippy re-use of episodes from his “Rocket Robin Hood” was memorable for me even in my pre-teens. I see they’re on YouTube. I’m sure they’re … not awesome, but a rewatch to understand how they influenced my later Spidey-experience might be informative.

LikeLike

Sorry for the delay in replying. It so happens that my mom was very down on TV, so my home viewing was extremely limited, and the television itself was substandard even for the 70s, which I’m sure you understand means not much better than a ham radio set. So I represent an odd combination of (i) ignorance of many cherished shows and other TV-ish things like commercials and news events, with (ii) extremely strong and focused memories of what I did see, as I put myself into “I’m really watching this” mode when I got the chance. (It may also amuse you that I was surprised to learn, by viewing at friends’ houses, that the characters in Star Trek wore differently-colored shirts, or in The Wizard of Oz, why the horse was of a different color.)

It would be extremely useful to examine how the TV and newspaper strip incarnations of specific characters provide rock-solid, incontrovertible faith in people’s perception of who these characters “are.” Superman is the obvious example, from the live-action George Reeves show and also from the 70s Superfriends, but also perhaps covertly from the Captain Marvel film serials of the 1940s, given that Superman had basically co-opted so much Captain Marvel content by the 1950s.

The most common outlook among scholars of pop culture is that there is no “text,” that a gestalt forms via all these influences and that’s who or what a character “is” at a mass level. Comics fans’ fixation on auteur-ship clashes with this outlook constantly, and it’s especially evident when the author represents this clash internally, as I’m seeing a lot when I read up on modern discussions of Superman.

By comparison, Spider-Man is way more focused in time and medium: one comics title for 15 years, plus one cartoon show for three seasons, plus one comic strip in the papers, before the explosion I described in this post. And that “explosion” really isn’t even very big relative to the decades of bewilderingly diverse Superman or Batman legacy before 1970.

Your comment reminds me that I missed out on “Spidey-ness” at this cultural level, to a significant degree. I may have been one of the only “text only” kids around, and thus all the more unprepared for the mid-70s franchise boom.

LikeLike

Pingback: Your mama’s apocalypse | Comics Madness

Pingback: The change of illusion | Comics Madness

Pingback: Being, having, and nothingness | Comics Madness

Pingback: “Nova” means “explodes and dies” | Comics Madness