The change of illusion

Six li’l issues of The Avengers. Do they really bear the whole weight of the history of Marvel Comics, and perhaps even of fan culture’s creative intestinal torsion? It can’t be that simple, but even at age thirteen-fourteen, I knew something was happening.

Six li’l issues of The Avengers. Do they really bear the whole weight of the history of Marvel Comics, and perhaps even of fan culture’s creative intestinal torsion? It can’t be that simple, but even at age thirteen-fourteen, I knew something was happening.

The term “the illusion of change” is of one Sean Howe’s conceptual throughlines for his Marvel Comics: The Untold Story: the industry or company attempt to reconcile the need for dramatic outcomes (change) with the need to preserve the familiarity of the marketable images and established story-portraits (stasis). It’s perfectly understandable in terms of something that gains public recognition because it’s dramatic but is now to be marketed as a fixed image/idea because it was dramatic. If I’m reading him right, this square-the circle contradiction puts story creation into flat-out crisis, for which the only solutions have been tap-dancing, e.g. crossovers and “deaths,” or distraction, e.g. collectibility. It’s related to the perennial gripe I’ve heard from comics creators for as long as I’ve known them: “the fans bitch that there’s not enough change, then they bitch because it’s not like it was.”

My chosen title for the post should let you know I’m going to play with the concept a little. It’s intended to partner with my older post ‘Verse this.

Early days

Howe introduces the idea in reference to 1970 or so, as Stan Lee’s editorial principle laid down to Roy Thomas when the latter became chief editor. It’s not my goal here to challenge the claim that “Lee said this to Thomas” in a journalistic way, but for the record, I don’t think a precise and confirmed moment or document is cited by either.

I’m more interested in whether the texts themselves turned out to follow it at that point, for which the obvious answer is, “In practice, no.” Lee had clearly done absolutely no such thing for the titles he cared about, The Amazing Spider-Man and The Fantastic Four, both of which, co-creators and collaborators included, represent remarkably solid novels full of nothing but character development and change. Furthermore, if this was an identifiable mandate intended to lock down post-Lee Marvel content, then Thomas’ editorship surely represents a complete defiance of it, overseeing tremendous expansion of Marvel content, and permitting and perhaps encouraging considerable writer impact on substantive content in the superhero titles. Or were you not paying attention roundabout Spider-Man #122? Or in further expansion, to the li’l thing called Conan the Barbarian, in which Thomas took the transition of innocent-barbarian to enlightened-king most seriously?

I’m more interested in whether the texts themselves turned out to follow it at that point, for which the obvious answer is, “In practice, no.” Lee had clearly done absolutely no such thing for the titles he cared about, The Amazing Spider-Man and The Fantastic Four, both of which, co-creators and collaborators included, represent remarkably solid novels full of nothing but character development and change. Furthermore, if this was an identifiable mandate intended to lock down post-Lee Marvel content, then Thomas’ editorship surely represents a complete defiance of it, overseeing tremendous expansion of Marvel content, and permitting and perhaps encouraging considerable writer impact on substantive content in the superhero titles. Or were you not paying attention roundabout Spider-Man #122? Or in further expansion, to the li’l thing called Conan the Barbarian, in which Thomas took the transition of innocent-barbarian to enlightened-king most seriously?

Yet there’s a glimmer of it. I’m looking at the brief phase when Gerry Conway was effectively Marvel’s chief writer, maybe 1972-1973 – and even though I just cited Gwen Stacy’s death as “change,” it became un-change soon, after Len Wein had replaced Thomas as chief editor. Both Howe’s book and my re-reading (see Spider-Schlep) confirm that there was a death-struggle between Conway as change-writer and the higher management as status quo defender which Conway lost. As I recall, too, Conway got sort of a rep for killing and mutilating and lobotomizing characters across his titles, only to see it re-set. But then again, in the longer run, yes, Gwen Stacy did die, in both textual usage and fan-culturally – the “fact” became set in stone for Spider-Man storytelling, as basically the cap for his origin story, and her clone wouldn’t become a Marvel character again for decades.

Crazy days

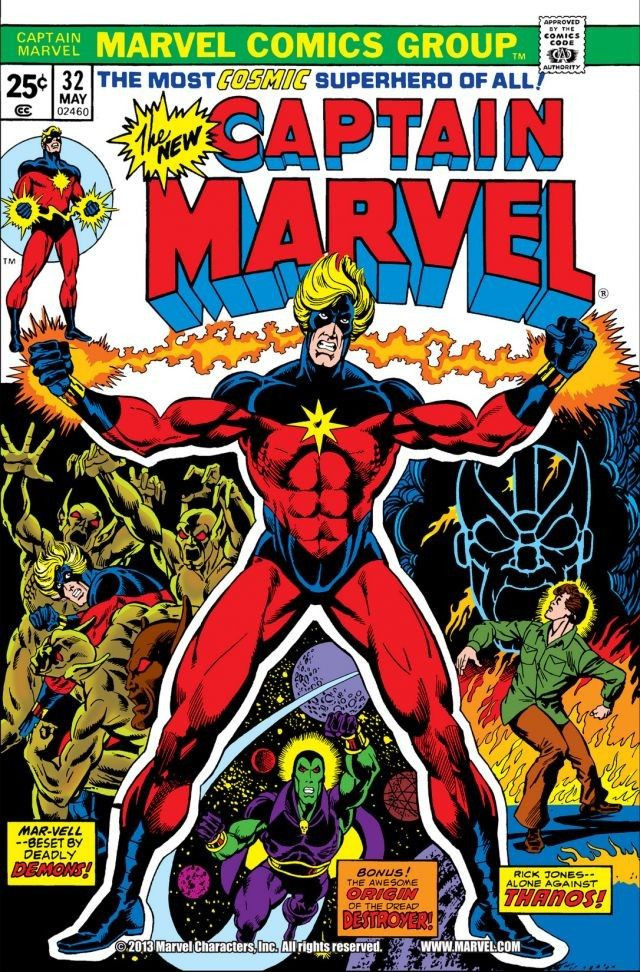

Through the mid-late 70s, after Thomas left the chief editorship, Marvel went through the whacked changing-editorship phase, Wein-Wolfman-Conway-Goodwin, even as the ownership demanded massive expansion of titles. The strongest writers of the time – Doug Moench, Don McGregor, Steve Gerber, Steve Englehart, and coming in a tad later, Jim Starlin – handily took themselves off the leash, creating proofreading cabals to bypass editorship and running their own story-planning/crossover sessions unchecked. Significantly, collectively, they seized upon Thomas’ and Conway’s best work and wrote it forward, changing stuff as they would, and moreover, expecting the changes to stick for whoever might come next. Some of those changes, even possibly frivolous ones, stuck surprisingly hard. (Case study? Tons. See Stars and garters for one, Cosmic muck for another.)

Through the mid-late 70s, after Thomas left the chief editorship, Marvel went through the whacked changing-editorship phase, Wein-Wolfman-Conway-Goodwin, even as the ownership demanded massive expansion of titles. The strongest writers of the time – Doug Moench, Don McGregor, Steve Gerber, Steve Englehart, and coming in a tad later, Jim Starlin – handily took themselves off the leash, creating proofreading cabals to bypass editorship and running their own story-planning/crossover sessions unchecked. Significantly, collectively, they seized upon Thomas’ and Conway’s best work and wrote it forward, changing stuff as they would, and moreover, expecting the changes to stick for whoever might come next. Some of those changes, even possibly frivolous ones, stuck surprisingly hard. (Case study? Tons. See Stars and garters for one, Cosmic muck for another.)

Readers of the blog know that I – in defiance of all fandom it seems – love the period with all my heart, in full knowledge of its various flaws. But this particular post is supposed to be non-nostalgic, so my “but but it was so great” talk is set aside. To anyone even a smidgeon into the management level, it was flat-out apostasy.

Cadence Industries cracked down hard on the madness via their suit/axe-man Jim Galton, resulting in an overlooked and – I submit – absolutely crucial couple-three years of Marvel history, both for content and for the readership culture. It’s pretty much synonymous with Jim Shooter approaching, then achieving the chief editorship, and then re-organizing and redefining the writer culture (see Context!). It was my first period of seriously buying comics so you can see the exact transition I’m talking about in posts like Never heard of’em and The book that wasn’t there. The writers re-shaped into a more obedient bunch, namely Wolfman, Wein, Tony Isabella, and Bill Mantlo. The texts show that all of them kicked in the traces but learned the hard way that they couldn’t (see EEEEEAARRRHHAAHH!), and no surprise that all the writers I mentioned in the previous paragraph, as well as Wolfman and Wein, quit or were phased out of Marvel during this brief period.

The case study

So, the Avengers, mid-70s, spanning the transition I’m describing. Englehart’s long run as writer produced one of my favorite stacks of comics, and yet, I freely admit it’s possibly his worst title at the time. Most of it is over-written and gaudy, full of MCI in its teeth-grinding form as “why write a story when you have this,” and stuffed with basic stupidity on both heroes’ and villains’ parts. His best work was obviously on Doctor Strange (see Buddha on the road, Steve – get’im!). However, the Avengers run is full of trenchant topical content, not as following-headlines, but honest and provocative grappling without a clear or simple answer: the Black Panther vs. the Black Panthers, Mantis and the Vietnamese junket (This one), believe it not but real romance between the Vision and the Scarlet Witch (The Vision, his semen, and his friends), and more. Some of it displayed naivete and some of it broke taboos, but none of it was trivia. It isn’t mere nostalgia to say the title spoke for the times.

So, the Avengers, mid-70s, spanning the transition I’m describing. Englehart’s long run as writer produced one of my favorite stacks of comics, and yet, I freely admit it’s possibly his worst title at the time. Most of it is over-written and gaudy, full of MCI in its teeth-grinding form as “why write a story when you have this,” and stuffed with basic stupidity on both heroes’ and villains’ parts. His best work was obviously on Doctor Strange (see Buddha on the road, Steve – get’im!). However, the Avengers run is full of trenchant topical content, not as following-headlines, but honest and provocative grappling without a clear or simple answer: the Black Panther vs. the Black Panthers, Mantis and the Vietnamese junket (This one), believe it not but real romance between the Vision and the Scarlet Witch (The Vision, his semen, and his friends), and more. Some of it displayed naivete and some of it broke taboos, but none of it was trivia. It isn’t mere nostalgia to say the title spoke for the times.

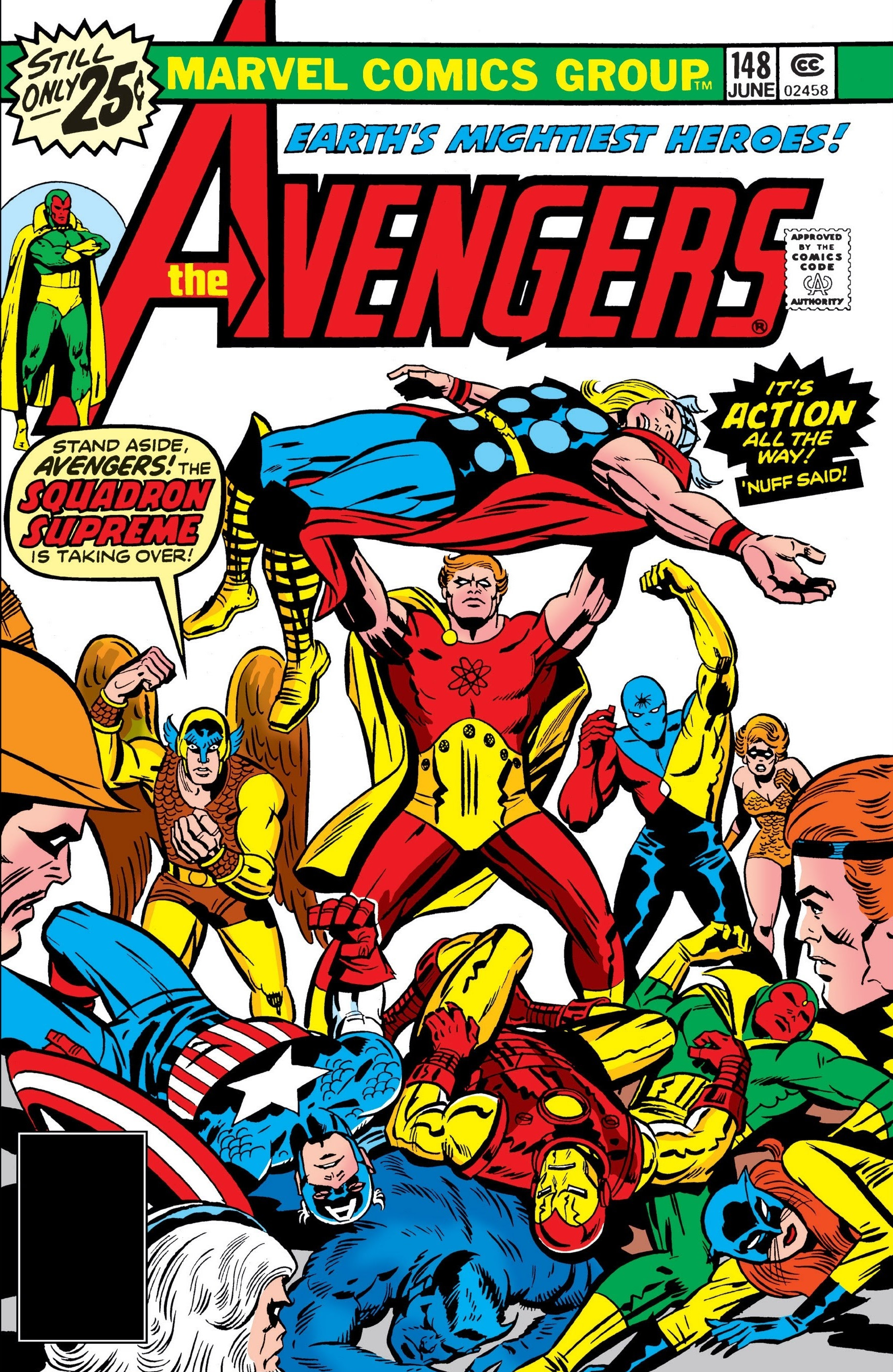

The editorial chaos came on display during his last year or two, when Marvel was so damn disorganized: bimonthly-or-monthly titles, constant delays, writers and artists on again off again Finnegan, series debuts-and-cancellations to make your head whirl, editorial reference captions doing no good at all on the ground. Fill-in issues? Ha! Easier to count the issues without reprints padding out the back half or holding the monthly place entirely. It takes a lot of squinting to follow the sequence in the #140s Avengers that really matters.

I’ve written about it in Faster, pussycat, And the horse you rode in on, and Time travel trippin’ up, but never quite summarized it well. The last phase of the Kang story was actually top-notch, turning a closed time-loop into a god’s-death story, and making a sojourn to the Wild West surprisingly fun; plus, in no way I can explain, actually doing an entire Marvel-meets-DC sequence with teeth bared rather than for cuteness. (Um – I don’t have to point out that “the Brand Corporation” is a callback to “Brand Ecch,” do I?) It is – frankly – the single best celebration of how Marvel’s older (1950s western) and newer (1960s) content was uniquely great, even when it wasn’t Spider-Man or the Fantastic Four.

I’ve written about it in Faster, pussycat, And the horse you rode in on, and Time travel trippin’ up, but never quite summarized it well. The last phase of the Kang story was actually top-notch, turning a closed time-loop into a god’s-death story, and making a sojourn to the Wild West surprisingly fun; plus, in no way I can explain, actually doing an entire Marvel-meets-DC sequence with teeth bared rather than for cuteness. (Um – I don’t have to point out that “the Brand Corporation” is a callback to “Brand Ecch,” do I?) It is – frankly – the single best celebration of how Marvel’s older (1950s western) and newer (1960s) content was uniquely great, even when it wasn’t Spider-Man or the Fantastic Four.

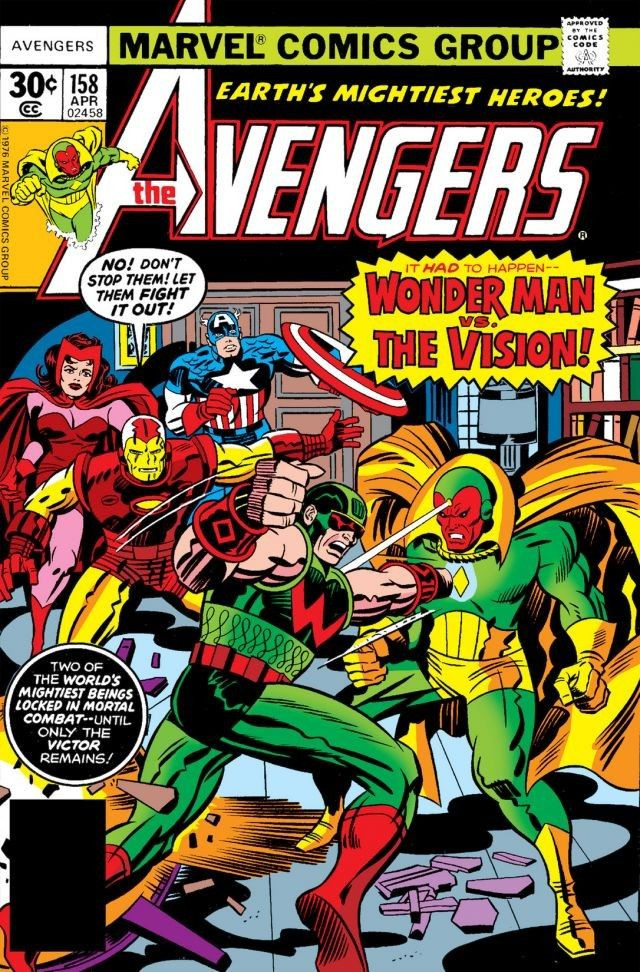

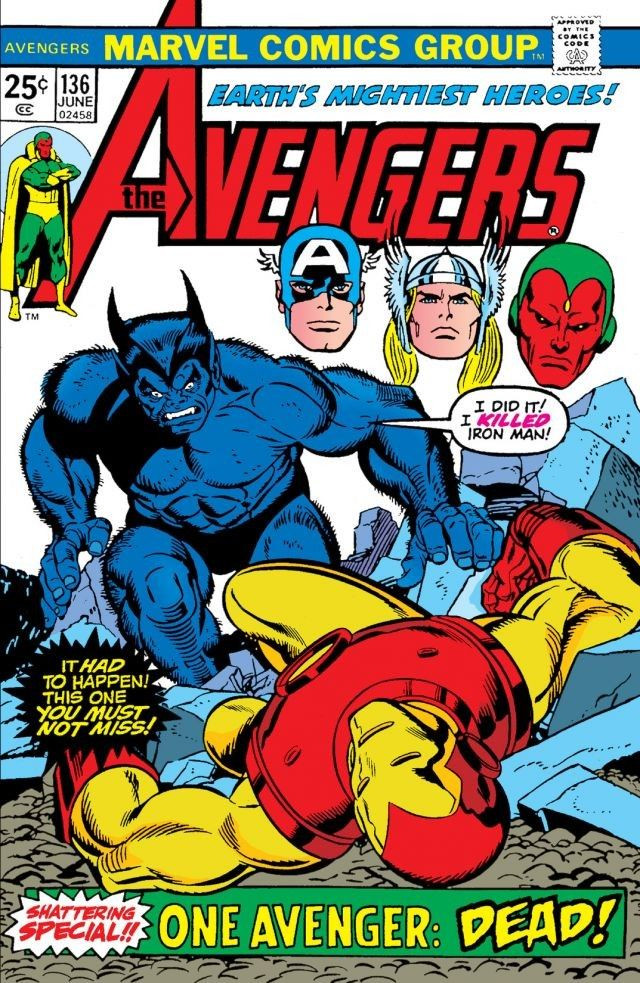

Englehart’s departure and the transition out of it is, upon re-reading, utterly jarring: the almost completely incoherent #150, then a couple of fill-ins by Conway which incidentally resurrect Wonder Man, and then Shooter taking over as writer beginning with what can only be described as a fill-in for a fill-in, as I’ve written about in Hitting bottom.

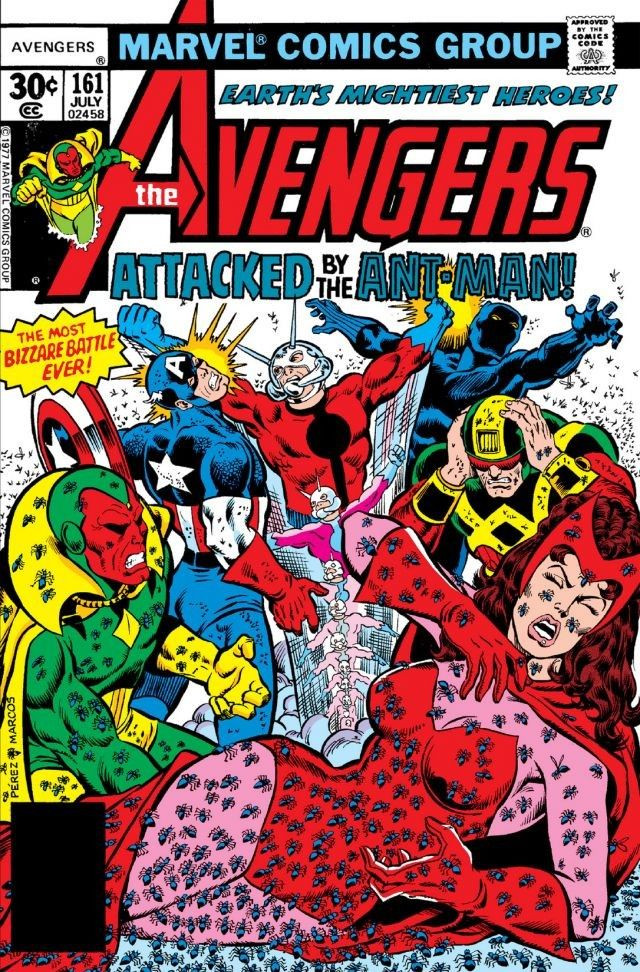

He only did six issues, at this point (he would return to the title later), and they’re hard to assess without being distracted by George Perez’s art; he’d come in during the final Englehart story but really nailed down his signature style right here. But it’s Shooter’s signature style too, or rather an aspect of his writing which often surfaced even if it wasn’t the totality. The most talked-about detail is Hank Pym’s instability, but that’s not isolated – the net effect is that the group is full of dysfunctional asshole protagonists everywhere. Shooter has written that he based all his characterizations on reading the characters’ entire histories, and I see no reason not to believe him – but also plenty of reason to think that he gravitated toward the negative with considerable force.

He only did six issues, at this point (he would return to the title later), and they’re hard to assess without being distracted by George Perez’s art; he’d come in during the final Englehart story but really nailed down his signature style right here. But it’s Shooter’s signature style too, or rather an aspect of his writing which often surfaced even if it wasn’t the totality. The most talked-about detail is Hank Pym’s instability, but that’s not isolated – the net effect is that the group is full of dysfunctional asshole protagonists everywhere. Shooter has written that he based all his characterizations on reading the characters’ entire histories, and I see no reason not to believe him – but also plenty of reason to think that he gravitated toward the negative with considerable force.

However, I’m not talking about one author doing the book his way, to be replaced by another, who’d go on to do it his way, e.g., Lee to Thomas to Englehart. This is content codification, which is something more, and not only that, it’s cultural: is, is, is. It’s not just these characters and this story, but the way these characters and their stories will be done from now on. If you re-read these, you will be amazed to see how much of the subsequent THE AVENGERS ARE material is set in stone, long before the Official Handbook or other summary-style presentations, and how thoroughly it effaces and replaces the prior characterizations and events. Hank Pym “is” a gigantic asshole – really? The Vision “is” a nonentity, his history effectively to be usurped by Wonder Man – really? Moondragon “is” a prissy bossy bitch – really? Hawkeye “is” an oaf – really? Yes, as of 1979 and going forward, really.

I also see the 1977-79 period as Frank Miller’s, John Byrne’s, and Chris Claremont’s journeyman phase, which would subsequently evolve into effective writer autonomy, or self-editorship, for each. Therefore anyone looking at the Marvel scene they dominated in, say, 1980, would have been justified to think that the Thomas-ish Englehart/Starlin approach was back on track after the hiccups and administrative reorganization of the previous two years. But …

The birth of ‘Verse

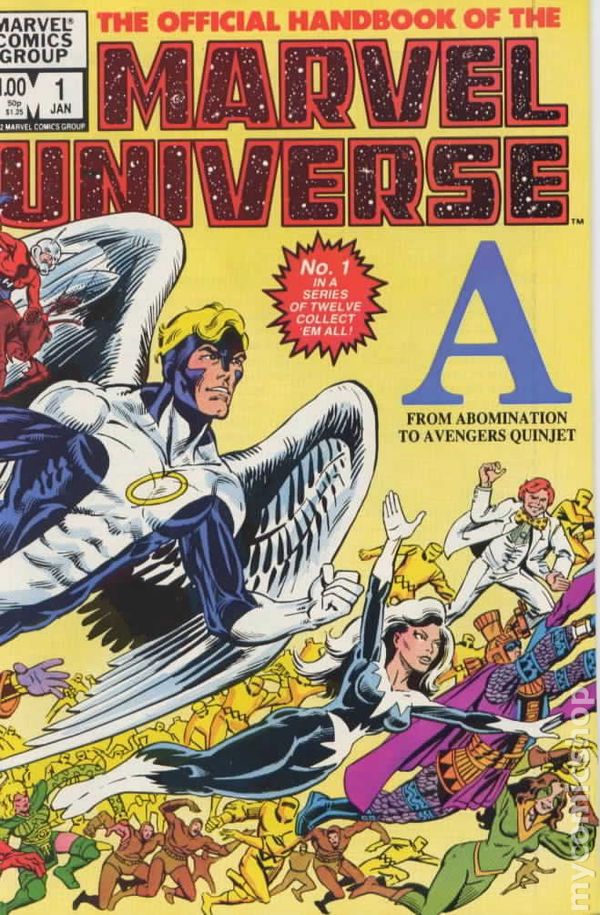

… there was another transition in the works, far more significant and far more lasting. And here, rather than back with Lee or Thomas, is when I think the illusion of change became a real thing. By that I mean, actual editorial policy, and soon, even with its own locked-down text. It’s worth reflecting upon: the Official Handbook is absolutely not merely a summary or encyclopedia; it’s a replacement for reading the older stories and also a model for how to read Marvel Comics going forward.

In the long run, I think that the illusion of change was its own stage in the change(s) of illusion. Story is always an illusion, a contrivance in which the dance of what-if and plausibility is poorly understood. In the 1960s, it’s reasonably clear to me that Marvel’s primary properties were indeed story-driven, in the ordinary sense of single texts and dramatic outcomes, whereas DC’s were emphatically not. But over time, story-as-such encountered the long-term marketing of memes, as well as the historical hassles of Marvel’s ownership and editorship, yielding a stepped result:

- 1960s into the very early 1970s: Marvel was effectively an underground comix company with uncharacteristic access to national distribution, with very few and very driven creators (see Context too!)

- Early through mid-1970s: the editor chaos phase, which allowed the underground-aspect to flourish for a number of ambitious and playful creators in a more scattershot, less novel-writing way, resulting in multiple bright spots in a sea of weird cruft

- Late 1970s through very early 1980s: the consolidation of owner’s priorities into policy and the pre-‘Verse Shooter stage, characterized by strict codification probably via Mark Gruenwald as far as creator-ideals are concerned

It’s wrong to say The Official Handbook introduced the new content in 1982. It had been mainly generated during the three-to-four years before that, such that The Handbook only completed the process of effacing and replacing the prior content and the prior means of writing and experiencing the stories. Like it or not (and there are reasons for doing both), Jim Shooter was the only person – ever – to assume Lee’s 1960s role toward Marvel’s content and the Marvel readership. He did so under very different corporate-and-ownership-and-licensing circumstances, and whatever may or may not have been said previously regarding the illusion of change, now, it was the Way and the Light, implacable.

It’s wrong to say The Official Handbook introduced the new content in 1982. It had been mainly generated during the three-to-four years before that, such that The Handbook only completed the process of effacing and replacing the prior content and the prior means of writing and experiencing the stories. Like it or not (and there are reasons for doing both), Jim Shooter was the only person – ever – to assume Lee’s 1960s role toward Marvel’s content and the Marvel readership. He did so under very different corporate-and-ownership-and-licensing circumstances, and whatever may or may not have been said previously regarding the illusion of change, now, it was the Way and the Light, implacable.

The latter phase of Shooter’s editorship, which is synonymous with and possibly better designated as the latter phase of Cadence’s ownership, is practically a textbook of the illusion of change. Most obviously, both Secret Wars ended precisely where they started, but the notorious axe-murders of many characters count too. How could that be? Let’s check’em out.

- Death as forced control over change, harking back to the fact that Gwen Stacy’s death (however it had been conceived by the creators) ultimately negated the basic arc of Peter Parker becoming or not becoming Spider-Man as its own story. This is Phoenix in spades – resolve the Scott-and-Jean relationship? Change up the membership without leave? Favor marginalized loser-Scott over fan-fave Wolverine? Nope – kill’er, and keep everyone in place and miserable just like they were.

- Death as sales-boosting shocker, harking back to the unexpected responses to Gwen and to Phoenix. Hey, this works, and gets a lotta attention back on us rather than on those damned Teen Titans who were swiftly eroding the X-Men’s cachet. So, Elektra. Note that it’s pure setup; you can see for a number of such characters that their continued presence in the title would yield change, so the death flatly ensures that such a thing doesn’t happen.

- Death as house-cleaning, affording a way to get rid of less marketable properties with the pretense of “drama” as had been worked out on the unplanned Phoenix and the planned Elektra model. So, good-bye Spider-Woman, good-bye all those villains killed by that pum-spak guy, good-bye anyone we don’t need.

And note, significantly, that sooner or later, none of the ones the fans really grieved over were actually dead. It’s the horror beauty of ‘Verse I’ve written about so much: rather than preserving continuity and constraint, it’s totally deceptive, as you can change whatever you like and claim you’re not, neatly splitting the difference between the fan-poles I mentioned earlier.

Consider as well the creators I mentioned earlier: Claremont, Byrne, and Miller. They’d initially replaced Gerber, Englehart, Moench, McGregor, and Starlin to keep bringing not-too-dissimilar content but thriving in the new Shooter-Gruenwald editorial environment, not least because they could make deadlines. They also all tended toward the same asshole/loser protagonist model that Shooter’s writing often favored. But you can see some struggling there from the start, more so for Claremont and Byrne and less for Miller (I suspect the heft of Denny O’Neil may have played into that) … more and more innovation as with Magneto that kept getting busted back, more crackdowns on rewrites and revisions, and almost-resolutions. By the mid-80s, their efforts seemed to me like the corpse kicking once or twice more, as Miller’s interest in Daredevil obviously waned (see Irish rage, Catholic guilt), also in the striking shift in Byrne’s work (see It is unwise to mock cartoonists), and the curious, perhaps desperate spray of meaningless change across the mutant titles which also reflected prying Claremont’s unofficial editorial role off of them.

Forlornly and without hope of effect, I plead that this isn’t a hit-piece against Jim Shooter. He had his part to play in it just as anyone else, and that play with those parts in it was an industry phenomenon, not a matter of individual agency. And the list of positive things he brought to the job, not least, keeping the damn thing afloat, as well as his sincerity toward the work (see Stillborn), are undeniable too. My goal here is to dissect the changes in illusion at Marvel that included the perhaps inevitable illusion of change as their outcome. To my knowledge I’m the first person to try to do that. One of these days I’d like to know what some of these writers and artists could tell me about it. I did, after all, pay those 20 and 25 cents into the experience, and my God did I care.

Links: Some thoughts on Jim Shooter’s first run on the Avengers (the first of several posts, read them all through the links)

Next column: Mustache match (April 9)

Posted on April 2, 2017, in Storytalk, The 70s me and tagged 'Verse, Avengers, Cadence Industries, Gerry Conway, illusion of change, Jim Galton, Jim Shooter, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Roy Thomas, Sean Howe, Stan Lee, Steve Englehart, The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0