‘Verse this

Cool! We got it all stretched out up there and we nailed it! Oh wait … why can’t it move? And it seems unable to breathe … and its wrists are bleeding …

It’s the worst thing ever to happen to my experience of Marvel and other superhero comics.

Let’s recap: in 1973, Marvel was still merely an imprint within Goodman Publications, which was wholly owned by Cadence Industries. Cadence was now run by a guy named Sheldon Feinberg, and Marvel was a mess: in 1974, Roy Thomas quit the editor-in-chief position in protest of some Marvel-DC pay-fixing shenanigans, and the position cycled through several meltdowns throughout the following year, first Len Wein, then Marv Wolfman, then Gerry Conway, and then Archie Goodwin. 1975 was also the year of house-cleaning at the top, when Jim Galton replaced Al Landau (who’d been Ponzi-scheming the whole thing), and shut down the magazine division in response to unionization. Licensing deals like the Kiss comic and Star Wars are all that kept the comics alive, and the long-running attempt to get Marvel onto primetime TV finally began with the Hulk and Spider-Man shows. (many thanks for all this to Sean Howe’s book Marvel Comics: The Untold Story) The chief editorship continued to be a disastrous position, especially since primary writers like Englehart and Wein were quitting left and right (Thomas stuck it out bitterly on Conan until 1980), and when Goodwin quit in 1978, hardly anyone but new people was left. Jim Shooter, the associate editor under Goodwin, took the position, over a Bullpen composed mostly of people about his age, about 27. His new hires were young too, and although Thomas, Conway, and Wolfman had been active fans prior to their jobs, this was the first time that fan culture characterized the workplace. Notably, Shooter’s chosen associate editor: the editor of the fanzine Omniverse, dedicated to mapping, time-lining, and circles-and-arrowing every character and event published so far in Marvel Comics, 25-year-old Mark Gruenwald.

Gruenwald first brought his love of canon into the conversations and workplace atmosphere, then into his editing, and finally into a project that would become not only directed toward the customer audience, but toward the culture of production. It dovetailed perfectly with Shooter’s policy of streamlining, some say axe-murdering characters that weren’t going anywhere or seemed unmarketable at the toy/tie-in level, while organizing the usage, appearance, and actions of the characters across multiple books at once, for maximum appeal to the new fan market in the new comics stores. (Insert your opinion about that here; it doesn’t matter to my point.)

The chronology goes: Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars (1), Marvel Age, The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars 2, and The Deluxe Handbook of the Marvel Universe. I put all these in a row because the Secret Wars series became part of the process of identifying who was and wasn’t “in,” what they looked like, and soundbytes to go with them. I am, of course, focusing on the Universe as such. Here’s the official page if you’re interested.

I am sorry that Mark Gruenwald died so young (1996), and I’m certain he was a nice guy. In fact, I’m positive: he seems the very model of the irrepressible, cheerfully exhaustive (and exhausting), wholly sincere fan, and the specimen of the breed is binary, either completely likeable or completely unlikeable. He played a big part in the excitement of the early 80s titles. He became the first setting-and-continuity man at Marvel, summarizing events and relationships, listing abilities and motivations, and for all I know, running seminars about the differences among mutant vs. cosmic vs. elemental powers. This is different from the prior editorial attention to some prior-story constraint. As far as I can tell, at first, it was entirely self-motivated, not a job description at all. Geek heaven, yes, but …

It comes down to that one word, the declarative of sum, indicative third-person present form, est – that verbal form of the equals sign, “is, is, is.” Cyclops’ optic blast is an energy-projection that delivers a physical impact. Captain America’s shield is made of adamantium, Wolverine’s name is Logan, Doctor Doom is monarch of Latveria, Thor is [however-much] tall, Jean Grey is dead. The word transforms the author of these statements into the observer of a vast and wonderful setting, most notably, in his or her very own mind.

I can talk about this because I’m there too. I say I am a fan of this stuff, but once the word is gets transferred out of my head and pretends it’s before my eyes, then I am now oblivious to the fact that I am actually the architect of the shared world, the hard setting, the universe, the canon. I can instead believe that I am looking out of my eyes instead of into my own head, and what I yearn to see out there most of all, is the face of God official canon, or in modern geekspeak, the ‘Verse.

I’ll start from the beginning. For the creator of stories, all of these are good things:

- consistency, consequence, comparison, constraint

Consider the comics creators using these ad lib within serial comics and across titles. Freely extending previous stuff, freely adding new stuff, and – crucially – freely ignoring whatever you want. With or without extreme rigor as the individual case may be. And guess what? Those readers, people exactly like Mark and exactly like me? We will happily devote ourselves to “make sense” of it, which feels to us like finding the sense, but which is actually a semi-schizophrenic, creative act of its own. When I do this, I make the continuity. But like religious fundamentalists, I don’t want it to be in here (in my head, where it is), but out there. Solid. External to myself. Real. Envisioned by a master mind. Intended.

You won’t find me criticizing Gruenwald here. I was doing the same thing at the same time, although I was younger and had less to work with. In 1975, I gave a presentation to my Extended Learning school group about the history of Peter Parker’s love life, culminating in the death of Gwen Stacy. I diligently re-read every back issue of the Kang-Immortus story (the one that eventually led to Celestial Madonna necrophiliac Tao sex) every time a new issue arrived, determined not to lose track of the grand vision. I kept on doing it – twenty years later, I mapped out every event in the first four Sin City books, figuring out the whole chronology criss-crossed among them, flashbacks’ content placed just so, and mailed the diagram to Dark Horse. Diana Schutz was very kind to me about it, and I’m sure she had the grace to put it in the drawer with however many similar documents had been painstakingly compiled for no reason on this Earth by other readers, each of us thinking he was doing the world a favor. You really don’t want to know how many chronologies and lists and diagrams I scribbled through the decades. Want to see my version of the proper chronology of Howard’s Conan stories? With a paragraph of justification next to each one, showing that both the deCamp-Carter sequence and the Thomas sequence were flawed? Sure you do! I say again, Gruenwald and I – and however many of you – sport the same funky feathers.

But we should never be let loose in a working comics bullpen.

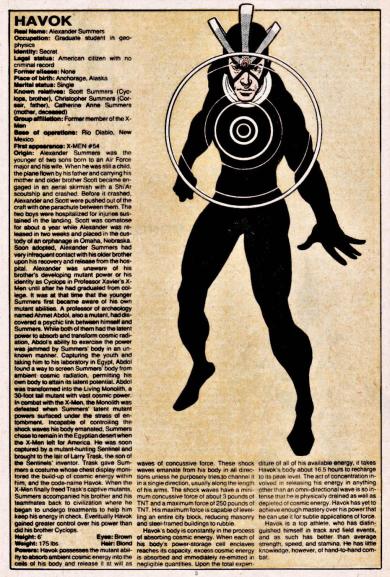

Remember Havok? Let’s say …

Let’s say I’m a writer. I’ve read some of the older comics. I read one with this guy in it, he seems fun and weird, I have the basics (Cyclops’ brother, right?) and the artist I work with is really good at those funky circles. Cool, I write him in. What is he like? Like what I remember from years-ago reading, the parts I enjoyed anyway, and that’s all. If I want to go back and read everything he’s been in, and make sure I’m consistent with it, I can – but frankly, I might do a little bit of that at most, and whatever I don’t like, I’ll ignore. Who cares if he ate cheeseburgers ten years ago and now I’m writing him as a vegetarian? I don’t give a fuck. I write a really great story about vegetarian Havok. The artist knocks it out of the park, you never saw such circles o’mutant power, and he leaves off the silly head-thingies because, come on. By the time any customer sees this story, it’s long gone for me, I’m working on some other thing.

Let’s say I’m a reader who loves mutants, mutant powers, mutant costumes, mutant groups, and mutant soap opera. I see Havok on the cover and I spike with simultaneous satiation nod-off and jolting excitement like unto a freebase, or even better because I don’t catch on fire. I read it! … and wait, he’s a vegetarian. Umm, didn’t I …? I could have sworn, flip, dig through the pile, find the issue, yes! He ate a fuckin’ cheeseburger, man, right there!! OK – let’s see how this might work? Is there a period of “silence” during which he might have come to a life-style decision? I start working it out, tracking the “is,” taking it as a given that Havok was this particular way, and then he became this other way, and therefore there must be events, a becoming-process, tacitly located in the fictional time between the two. These events absolutely must exist, in my mind. I call attention to this, I get a letter published about it, and the concept of an intermediate story about Havok, as yet unwritten – no wait! As yet unrevealed! – becomes a part of our reader dialogue.

Speculation is permitted, held to rigorous prior-plausibility standards that would shame NIH grants. Is there a possibility that someone was mind-controlling him in the earlier issue … come to think of it, everyone knows this other villain in that earlier story is a cousin to that mind-control guy; also, Havok was a big jerk in that story, and in this one, he’s kind of cool, so maybe, yeah! I want this comic to make sense, I love the way he’s drawn too, so I write up this hypothesis, and I share it with my buddies and soon enough, there’s a letter published in the comic about it, and at the comic convention panel, someone asks the artist about whether it’s true Havok was mind-controlled by (insert proposed candidate) in that earlier issue, and the artist sure seemed nice about the idea, so! There! It’s not official yet, not like the perceived change from non-veggie to veggie is completely accepted by me and all of us as official fictional content, but it feels good to figure it out, to resolve – no, to discover a possible hidden sense underneath it all.

There you go. Writers write, artists draw, and readers make canon. The creators can be ten times less attentive to the list of c’s than they were at Marvel in the 1960s and 1970s, and if the comics are good enough, then the readers will still make canon out of it. They’re less rigorous than they think: if the story is good, then completely arbitrary changes like the headgear are simply absorbed without stress, although if it’s not, then that “mistake” or “inconsistency” or “unjustified change” will surely be brought up with great anger.

The creative culture at Marvel at that time facilitated this with certain long-running teams (Lee/Kirby, Lee/Ditko then Lee/Romita, Thomas’ copyright-mining facility, Englehart’s kooky piss-taking version of the same). More creators during this Marvel era concerned themselves with consistency, consequence, comparison, and constraint than any previous superhero comics creators. But the work of canon was done by the readers, who are also their own audience for canon, because the writers and artists sure as hell are not. According to Howe, Roy Thomas as editor-in-chief kept index cards to keep tabs on characters’ current doings, but Thomas says he didn’t do that actually. If he did, if any writer ever paid attention to Roy about them, aside from maybe Gerry Conway, I’ll eat that stack of cards.

Shooter’s and Gruenwald’s editorship was different, especially at about 1980, when reinforcing canon became a marketing strategy, however sincerely created originally, and then an editorial policy. Instead of “is” being whatever we’ve come up with now, it’s what must be held sacred against what we come up with. When someone’s version of canon becomes an imposition – effectively law , on the work in progress – whether on the timing of events, the extent and capacity of powers, locations, motivation – when it becomes a piece of the job to conform with it, as an explicit body of recorded information – then together, all those useful c-words have together shifted their whole function to continuity as a priority, and transformed into “official” canon, ‘Verse.

Which is completely dysfunctional. I say this to you now: Canon is a wonderful form of connoisseurship, but ‘Verse is a disastrous creative device. Drive that into your brain.

Readers love canon partly because they make it themselves, and by definition they can interpret and argue about it – and in such things, geeky happiness abounds, including the feuds and tremble-voiced hissy fits. Canon exists in a state of fun. ‘Verse, on the other hand, is when an architect of canon jumps into the front end of the creative work and starts saying what creators can and can’t do, what they must include, what they can’t abandon, how things work so that what you propose will only confirm what something earlier showed, knowing what change is coming so the road to it can be properly paved … and from that point forward, living a year ahead in the future, working like a dog to make sure that down the road no terrible, frightening, ‘Verse-threatening failure of continuity will be spotted. Official canon, ‘Verse, exists in a state of fear.

Continuity-centric fandom never realizes that once they achieve their ideal of no more continuity arguments, that also means, no more fun.

But wait, you say, motivated by your deep, true, and loyal love for these comics, don’t the writers want to have it all laid out for sure? Surely they are ashamed and chagrined when despite their best efforts, a lapse of vigilance yields a continuity failure!

I have to hurt you deeply now. (deep breath) ‘Cause I’ve talked with them about it, twenty-five-plus years ago at the very crest of comics’ mainstream-breakthrough, hanging out, drinking, first a friend, then becoming a comics guy, having literally felt the shift in the past months from “This is Ron, he writes a lot of fan letters,” which yields a pleasant but twitchy silence, to “Look, Ron’s here,” in which I’m included in the current discussion about comics or not-comics as the case may be. I tell you that the pros don’t care a bit about your love of canon. Discussion of continuity within it baffles them.

If they started as fans, they may dimly remember it, but any interest in it as a thing is long gone, now that they are scripting and drawing months ahead of the readers’ heartfelt experience with it. They cultivate the skill of nodding and smiling when buttonholed by a hard-liner fan about the vegetarian thing (or what a power can do, or who was whose sister in which alternate universe, or how he could have been here when over in this title, he was over there). They even have a signal by which they inform a nearby fellow pro that they have had bloody well enough of fanwank about continuity for now, and the nearby guy comes over and rescues them. I am not kidding. And I’m not telling you what it is.

What will confuse you is that many of them care deeply about the quality of the stories and art. They do in fact value past events, visual things, actions, and outcomes … but it’s for those exact things in and of themselves as they remember them, not merely because they were published, and with no regard to their exact published form. They do in fact value “setting” (a complex word) but only as the current story’s vassal, with abandoned and added parts as needed. This is opaque to the fan-mind, in which continuity is a means to confirm canon and extend it (consistently, mind you!), but you see, to the pros, only the quality at the wave-front actually matters, going forward. They incorporate piecemeal and with varying degrees of analysis. Some writers like to pick a lot of cherries and some don’t, but a codified body of material like this …

… is the very last thing any of them care about. And I’m talking about your favorite writers and artists, the most wonderful, jaw-dropping, series-saving, comics-saving, character-saving, longest-running, super-best ones. Not the “lazy” or “careless” ones, but the one you feel you could not live long without. Tell you a secret? That guy hasn’t re-read the sequence of past issues of his very own book, that he wrote and/or drew. And he isn’t going to.

Even the guy who invented a breakout character, wrote and/or drew the issues, delves deeply into the character’s past, exerts authority in discussions about the character – he’s running on aesthetic energy of the moment, drawing on what he’s absorbed throughout the process, not careful review and continuity-consistency. He isn’t going to read that “official” Marvel Universe entry page. Ever.

Ah geez, and that goes triple-exponential for powers-enumeration and powers-quantification, and don’t even get started on powers-justification. That’ll be a post of its own one day.

So, pre-Universe, sure there were Thomas and Englehart, the first ascended fanboys, who did come in breathing hard through their mouths about the Sub-Mariner vs. Torch fights of the 1940s and about what Spidey did that one time … but through the period of their big impact, along with others like Steranko and Starlin and McGregor, there was no toothy policy about it, no editorial mandate, no manual, no conferencing for the upcoming year (unless you count dropping acid together), no list or summary of what “was” the case. The editor didn’t run continuity meetings, but instead just did his best to corral what was happening into current captions. The list of c’s was about making the wave-front better and more fun, and when inconsistencies cropped up, when stupid-stuff got tossed in, well, later, those could be ignored just as the interesting stuff could be incorporated, and by much the same process. The readers could debate about canon all they wanted, and the editorship could suck it insert all those “see Other Book ##” captions they could keep up with, and learn to grin and bear it. Continuity mistakes? Sure, why not, who can help such things in such a situation? Back then, No-Prizes were fun. The term “Marvel Zombie” didn’t exist.

I know this must be an extreme minority view, but to me, in becoming a ‘Verse, the Marvel Age of Comics began to die – like a real body, not all at once, and some pieces twitched for quite a while – and the later zombie-term is incredibly depressing in its aptness. In the mid-80s, I looked at the Official Handbook my friend was so happy to buy, and I diagnosed it instantly, this is terminal. But blame is not what I can do. I find reading about Mark Gruenwald’s life sobering, and I had to stop, because I get it, I understand the love.

Click the ‘Verse tag to read the posts leading to this one

Links: The Merry Marvel Marching confusion

Next: Let there be nipples

Posted on April 23, 2015, in Commerce, Gnawing entrails, Storytalk and tagged 'Verse, Cadence Industries, canon, Celestial Madonna necrophiliac Tao sex, Diana Schutz, fanwank, freebase, Goodman Publications, Havok, Jim Shooter, Mark Gruenwald, Marvel Universe, Marvel Zombie, microdot, No-Prize, Roy Thomas, Secret Wars, Sheldon Feinberg, Sin City, Steve Englehart, The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Bookmark the permalink. 18 Comments.

“I have to hurt you deeply now. (deep breath)” THIS is the why I love reading what you write.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are there any comics that, in light of the “‘Verse phenomena”, actively attempt to thwart it? I.e., purposefully disregards its own “canon” in a knowing way? Alan Moore’s “Supreme” jumps tom mind, though I don’t know if it really qualifies (it’s maybe more Moore-style meta-commentary on Superman).

LikeLike

I don’t know. People more hooked-in to today’s superhero comics will have to weigh in, for that one.

But I’m replying to state that I don’t seek such work either. As I see it, when the creators utilize constraint, comparison, comparison, and consequence in their stories, then everything we love about canon and continuity will be happening. I enjoy that so much I cannot even tell you.

I hope with no hope at all that people reading this will understand that I’m criticizing ‘Verse not because it supports canon, but because it actually, in fact, ruins it. I am in the completely invisible position of wanting canon back by recognizing that ‘Verse is not the way to get it.

LikeLike

At this point, my biggest hangup is consistency in canon to character development as far as personality and relationships go. Seeing that get thrown out regularly is the part that loses my investment into getting back into comics a lot.

For example, I got into Iron Man in the 80s, when Stark was a) facing real consequences to alcoholism, b) facing real consequences of his technology being used by others to harm people. It was a pretty great time for his development as a character – the war profiteer turned hero…actually having to face the full legacy of his work and see what does it mean to be a hero both in terms of his creations and his personal relationships? During this, he gives up membership to the Avengers to take on the US Army for using his tech…

Fast forward to the recent Civil War crossover, where Tony is now super pro-government? And partying all the time?

It’s the character growth re-set button stuff that pretty much keeps me from getting back into modern superheroes.

LikeLike

So … this gives me the opportunity to suggest changing the phrasing constructively. Instead of saying “consistency in canon,” just say “consistency.” In and of itself. Never mind canon as a concept, stick with the idea that Iron Man has this history, so treating that as a consistent feature matters and is very good. As opposed to dropping the consistency, which if one wants this all to be a story, is bad. (I’m leaving out approaches which simply abandon that as a creative or audience goal.) One doesn’t need to bring canon into that discussion at all.

LikeLike

The G+ discussion of this post is mighty lively. It’s circle-shared, so you have to circle me to see it if you haven’t already. (Note to self: adjust further automatic shares to “public”)

LikeLike

“Want to see my version of the proper chronology of Howard’s Conan stories? With a paragraph of justification next to each one, showing that both the deCamp-Carter sequence and the Thomas sequence were flawed? ”

YES!

Apart from that….

I agree with this post, in general, but I think you are generalizing too much. You say that writers didn’t write that way… well, not even Gruenwald?

By the way I talked with Gruenwald, once (when he went to an Italian fair and I won a signed book in a raffle, I think I still have the pictures), but we talked more about Italian food than about comics (to tell the truth, he was not one of my preferred authors).

And I have the SECOND printing of “Squadron Supreme”, some authors really love their books too much….

I am not sure about how much real weight the “verse” had in the reality of comics publishing, even under Shooter and Gruenwald… this is the time when a no-name new penciler called Frank Miller write a book for the first time in his life, and right out of the bat Shooter allow him to add a totally new love interest for Daredevil called Elektra (totally ripped off from Will Eisner’s Sand Saref: as Miller gleefully admitted years later, if you have to copy, copy from the best). In less than a year he is allowed to totally change Daredevil’s origins adding sticks and a different explanation for his powers.

The stories I have heard are about a different kind of pressure from above, directly about the STORIES: the most famous is about Phoenix’s Death. It’s intriguing the way Shooter’s edict has a moral base: “she killed millions of people. Even if they are asparagous-people, they were people. She has to die”. It’s very similar to a decision I made in a old Spione game I posted about, if you think about it. Maybe it’s for this reason that I think that in this case, Shooter was right? (and I have seen the “alternative” Byrne and Claremont ending: it really sucked)

LikeLike

I noticed your earlier comment about how the Official Universe wasn’t very continuous in practice, and knew it would come up here. I agree. Nothing I wrote says that the ideal of perfect continuity was ever achieved or even approached. In fact, that supports my point – that adding it as an editorial step doesn’t achieve anything, not even its purported goal regardless of whether one likes that goal or not.

LikeLike

Oh yeah – and I know no one ever believes this, but nothing I’m writing carries any specific judgment of Jim Shooter’s editorial competence, yea or nay, in general or in a specific instance.

LikeLike

That is still a pretty sweet poster.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Who I am | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: It is unwise to annoy cartoonists | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Sex and sex and sex and sex | Doctor Xaos comics madness

Pingback: Context! | Comics Madness

Pingback: Michel Fiffe » COPRAVERSE : Stickers, Subs, and Criticism

Pingback: The change of illusion | Comics Madness

Pingback: On and on and on | Comics Madness

Pingback: Recursion isn’t just a river in Egypt | Comics Madness