Batpulp

I encountered Batman oddly.

I encountered Batman oddly.

The pile of comics I’d inherited were Marvel-heavy with only a little bit of DC, and that leaning toward sword-and-planet or horror. Yes, there was the TV show, running in syndication by the time I saw it, but my TV viewing was strictly limited and I’d only managed to catch a couple of episodes at friends’ houses. I’ve learned to appreciate their corny and often sly humor since then, but at the time I wasn’t interested or, significantly, invested enough to have an opinion. So of all places, my foundation learning about Batman and Superman came from Jim Steranko’s History of Comics, acquired as a gift from a step-sibling.

This was odd because to everyone else, Steranko was pulling off the curtains to reveal that DC’s touted “The Golden Age of Comics” was bare-faced nonsense, and that the costumed comics heroes were born directly from, as he called them in a chapter title, The Bloody Pulps. So here I am at 10, getting educated in the expose as if it were the basics.

The comics he referenced were completely unavailable at the time. I have no confirmation for saying so, but I speculate that the last thing Warner Communications wanted out there at the moment was images of Batman hanging a guy (mutated lunatic or not) from his plane. Denny O’Neil, Len Wein, Archie Goodwin, Steve Englehart, Neal Adams, Bob Brown, and Frank Robbins were even at that moment retooling the comeback of the Dark Knight Detective, but hampered by the last couple years of the original Code, they couldn’t give him his gun or have him kill anyone, so the result was the weird hybrid of ruthless nocturnal avenger + Dudley DoWright that we know and love today (see The not so secret cabal).

Since then, what with tons more histories of comics available and with plenty of revisitations, there’s not much for me to add or say or provide insight for, except that you can share with me the enjoyment of recently reading the entire run of the first couple of years. I’d read a few stories piecemeal – the early Joker stories, for instance, have been available for a long time – but just now is the first chance I’ve had simply to delve into the Finger, Fox, and Kane (or “Kane” with Kane’s signature) Batman as a body of work. It prompts me to re-articulate my Striking twice, someday rantings about the Metal Ages of Comics, lucky you.

Since then, what with tons more histories of comics available and with plenty of revisitations, there’s not much for me to add or say or provide insight for, except that you can share with me the enjoyment of recently reading the entire run of the first couple of years. I’d read a few stories piecemeal – the early Joker stories, for instance, have been available for a long time – but just now is the first chance I’ve had simply to delve into the Finger, Fox, and Kane (or “Kane” with Kane’s signature) Batman as a body of work. It prompts me to re-articulate my Striking twice, someday rantings about the Metal Ages of Comics, lucky you.

You can swat me with the willow branch if you want, but I’ll cop to being skeptical that these were any actual good until now. But the newspaper-strip style that informed this period of comics really works, especially when I think about the incredible pace and clarity of The Phantom. The stories clip along and they are great at quick cuts in the right places, blowing right past annoying transitional content. Batman is notably without internal conflict regarding his origin and ethics. Also, who knew – despite being mostly awesome and scary, he can also get shot, or outnumbered, or surprised, and at two memorable moments, outfought hand-to-hand by the Joker.

Speaking of ethics, let’s run it down:

- The stories are freaking littered with bodies. The villains are all about murder, or murder + money, either way, and it usually takes a few to pile up before Batman figures out enough clues to find the guy. He deliberately waits for more bodies sometimes, even when he knows the victims are gonna get it.

- And the goons! My God, do they die and die again. Special mention to the ching-chong-chinamen who get crushed beneath their own Green Dragon statue, en masse, quite graphically.

- Batman’ll kill a guy. He favors throwing them off high places, and the captions helpfully confirm the fatalities in most cases. He’ll do it with a kick (“SNAP” says the sound effect from the guy’s neck), or with a rope strangle, or via a nearby vat of acid or other useful item.

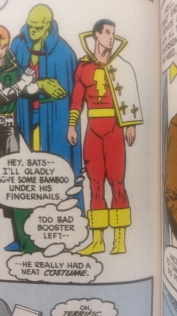

- His most notorious kills include shooting the Master, who’s a vampire, and hanging one of the poor ol’ monster-lunatic guys as you see above, before going on to take out the last one of them by gassing him atop a skyscraper, so he falls to his death. He expresses a bit of remorse in the latter story, as the monster-dudes aren’t responsible for their state. [I’m not 100% sure, but Fox is possibly the more bloodthirsty author than Finger, story by story.]

- He isn’t one bit conflicted about it as a general thing. All criminals should die, die, rrraah; when one guy electrocutes himself, it “saves the state the price of the chair,” and that’s a typical line among many others. The only exceptions are a Jekyll-and-Hyde guy, who dies, but Batman says “For once” he wishes he hadn’t; and the mysterious Cat (the original name of Catwoman) whom Batman definitely has the hots for and deliberately permits to escape.

- The police aren’t fond of Batman, and he often has to scamper outta there when they show up; similarly to Spider-Man thirty years later, they’re not above taking potshots at him on his way out. Once in a while an individual cop will muse positively about him though. There’s no shred of cooperation with them. Gordon doesn’t know he’s Bruce Wayne and is in the stories mainly to gab sensitive police information to Bruce, not knowing Batman is listening.

Other details are of some interest from a comics reader’s perspective. His original bat-ears are very ear-like, being long, slanted outward, and set where his real ears are; although they soon become vertical and pointy, they remain on the sides of his head and also keep their scalloped shape so they’re still recognizable as ears. The “horned” look settles into place a while later.

Money and status are strange, and remind me of movies from the same period. On the one hand, clearly there’s a moneyed gentry who swan about and have weird obsessions and feuds, but on the other, there’s a “criminal class” which has its own hierarchy and has nothing better to do than steal the rich bastards’ gems and piles of cash. Neither is particularly sympathetic, and hardly anyone in the stories stands in for “us,” i.e., people who are neither. For his own part as a wealthy guy, socially, Bruce is completely useless – very Scarlet Pimpernel – and his fiancee Julie Madison is present mainly to denigrate him for it. (Whoa – fiancee? wow)

Anyway, I was also anticipating a big shift tied to the initiation of DC’s in-house Comics Code (later to become the standard for the Comics Code Authority), knowing that it had been adopted mainly due to Batman’s bloodthirsty shenanigans, and associated with the introduction of Robin. But the stories during Robin’s first year are really interesting in these terms.

Robin himself is a little thug; if he was supposed to make things lighter and softer, well, I’d hate to see something that was intended to be the reverse. His daredevil grin is genuinely disturbing because it usually accompanies maiming someone.

Robin himself is a little thug; if he was supposed to make things lighter and softer, well, I’d hate to see something that was intended to be the reverse. His daredevil grin is genuinely disturbing because it usually accompanies maiming someone.

If anything, the action gets a little grittier, and the physicality of dangerous fighting becomes more detailed. Batman and Robin wrench their joints when they save themselves from falls, they trip over unexpected obstacles and otherwise suffer from pretty realistic bad luck, and although their outfits are armored, they openly worry about head-shots and take care to strike from surprise.

The stories remain entirely vicious toward all and sundry. True, Batman himself accounts for a few less bodies per time-unit, but the Joker is introduced along with Robin, and the early Joker is a fucking creepy killer. So the net effect is more scary rather than less, and the general standard of littering the plot with the cadavers of unfortunate participants holds.

I am no particular fan of Frederic Wertham, and most of his analysis in The Seduction of the Innocent is rot … but I must admit that Bruce’s and Dick’s relationship does look dodgy, even allowing for different-times-different-values. My suspicion is that the artists – by all accounts a dubious lot who couldn’t get any other work – were bored and irritated by the chumminess and threw in a little innuendo when they could get away with it. (There is, incidentally, no Alfred.)

Simultaneously, the comics begin to address readers, specifically kids, with Batman delivering occasional lessons or grinning at you from the page. Robin grins in the fiction as mentioned above, but Batman never does – it’s only in isolated “snapshot” panels as asides to the reader, in a big toothy way that feels very artificial compared to the gut-punching, neck-kicking action in the surrounding panels and story. The occasional similar panels that call for readers to become “Robin’s Regulars” (who apparently include obedience and nationalism) are just weird. I mean, he and Batman are still dodging cops’ bullets and are fully aware they are themselves basically criminals, and yet he’s touting law-and-order and helping ladies across streets.

Anyway, there are lots of articles like this scattered through the internet, and I won’t go on about it. One thing this blog has netted me over the years, though, is access to some closed online groups of really good comics scholars, way better than me. And without disclosing much, I can say that my dismissal of the Ages of Comics is standard for those who study them. Gold, Silver, et cetera, my ass. I’m pretty confident in laying it down now:

Early superhero comics were pulp fiction, full of guns and bodies. This went right into their boom as WWII fiction, and it was basically a given that a superhero killed bad guys who had it coming. The most visible of the bunch, Captain Marvel in his movies, was terrifyingly willing and casual about it. As National Comics formed and the in-house DC Code was instituted, the heroes they’d acquired cleaned up a bit, but that’s all.

The really ho-ho-chum Highlights Goofus-and-Gallant look and feel for those heroes is a Fifties thing, and should be understood as (1) quite brief and (2) very much to National’s advantage because the other companies were forced to be like them in order to publish at all. Although it set in hard with Batman and Superman especially, it was also subverted almost immediately by writers and artists, most notably with the Flash and soon throughout the Sixties with the Metal Men, the Doom Patrol, and the Secret Six.

Just how that effect dovetails with Lee doing his thing with like-minded artists over at Marvel during that same period, who knows. Either National did it first and Lee did it more-and-better, or Lee doing it made National step up their game, or they should all just be considered one big phenomenon – whatever.

What is known is that National (now National Periodical Publications, and now publicly-owned, bucking for its Warner merger) was rocked by Marvel’s newsstand success and they looked around for ways to distinguish themselves. So in 1968, the term “Golden Age of Comics” was coined as a marketing device, partly in an appeal to originalism and partly to claim that these heroes were wholesome and decent, not like those grubby psychedelic whatnots over at Marvel. That their alleged content for this Golden Age corresponded pretty much to 1958-1960, and not to 1938-1945 even a tiny bit, seems to have escaped everyone but Steranko. [see comments for more/better detail]

I think this has everything to do with youth culture and the Vietnam War. If you were into Marvel, you were probably into Warren Magazines and might have copped an issue of Snatch Comix too, and you didn’t give a shit about anyone’s mommies’ heroes with flags waving in the background; if you were into DC, you kept that regulation crew-cut, subscribed to Analogue, and cared greatly about whether science fiction would remain “pure” and “hard,” and you would not forget the Lost and Golden Times. Professionally, the situation was way more mixed, but the fandoms polarized.

It received a big push when DC, now firmly ensconced within Warner, licensed the long-fallow Captain Marvel from Fawcett, rebooting him as Shazam (the title, not the character) with his own TV show. As I wrote in Marvelous, meet Miraculous, they had the difficult job of reconciling Superman with his historical rival who, it must be admitted, outdid Superman in zesty cosmic terms. So the solution was to focus on Captain Marvel as goofy and cartoony, a real kids’ comic hero, as a contrast with the new Superman, recently made somewhat naturalized and humanized by Denny O’Neil.

I don’t know when people started talking about a Silver Age – it might have been right away as implied by there having been a Golden one, or it might have been after the big editorial shifts of 1968 and the resulting huge shift in content at both companies starting at about 1970, and thus retrospective. It’s not surprising that DC fans cited the Barry Allen Flash as the pinpointed origin whereas Marvel fans cited the first issue of the Fantastic Four.

I’m sure that Bronze, Iron, and the more dedicated attention to Ages as such is a late-1980s thing, tied very tightly to the fabricated myth of comics “growing up” via Alan Moore and Frank Miller (the former, to his credit, has never claimed such a thing). I think it found its indoctrination for fandom primarily in the inclusion of Captain Marvel in the Giffen Justice League International – specifically in the sudden, utterly non-historical claim that the hero retained the mind of Billy Batson at all times, and that there was no grown-up mind involved at all. So now he was safely made goofy, credulous, and basically stupid, and the whole concept of the Golden Age itself as the same, or “light and soft,” from 1938 through 1960 or so, was set into place right in time for Miller to have made men of iron of us all.

I’m sure that Bronze, Iron, and the more dedicated attention to Ages as such is a late-1980s thing, tied very tightly to the fabricated myth of comics “growing up” via Alan Moore and Frank Miller (the former, to his credit, has never claimed such a thing). I think it found its indoctrination for fandom primarily in the inclusion of Captain Marvel in the Giffen Justice League International – specifically in the sudden, utterly non-historical claim that the hero retained the mind of Billy Batson at all times, and that there was no grown-up mind involved at all. So now he was safely made goofy, credulous, and basically stupid, and the whole concept of the Golden Age itself as the same, or “light and soft,” from 1938 through 1960 or so, was set into place right in time for Miller to have made men of iron of us all.

So, I call bullshit. There were definite publisher and editor shifts which opened and closed doors of subversive or rules-changing creative activity. There were phases and periods of distinct trends in comics, probably numbered in the dozens, and overlapping rather than sequential. There are absolutely correspondences between what was acceptable in a superhero comic and what was acceptable in pop culture generally, at different times. But the standard progression from a light, idealistic, non-gritty Age shifting by steps, ultimately to a hard-edged, explicit, mature Age, is pure fan mythology and not worthy of a moment’s consideration by anyone who really wants to know about comics and superheroes.

Posted on June 10, 2019, in Commerce, Heroics and tagged Ages of comics, Batman, Captain Marvel, Detective Comics, Justice League International, Shazam, Superman, The Flash, vigilante. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

Very interesting. Your unique perspective makes me rethink things that I thought I knew all about. As always. It’s not easy for huge nerds (such as I) to see differing points of view about comics and just be plain fascinated. So please take this praise and never stop blogging.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. I super needed that, and not just for ego stroking. It’s been tough to figure out how to reconcile Patreon, blog, Adept Play, and YouTube, with the past year’s added complication of creative work that I don’t own. I’m taking your comment both as reassurance and the good kind of responsibility. Thank you.

LikeLike

Not much to add myself, but I’ll just nod in agreement with DOC and say that your work, as always, is much appreciated Ron.

LikeLiked by 1 person

With a little inquiry into the groups I mentioned, a noted scholar (no sarcasm! real deal) has told me:

This doesn’t surprise me a bit: that they arose as connoisseur commentary, not as analysis, much like the auteur concept in film theory or the various social myths like Bystander Syndrome or Stockholm Syndrome.

I’m still waiting to learn whether my remembered reference to 1968 for “company” reference to the terms is valid. I wouldn’t be surprised if a deliberate challenge to “the Marvel Age of Comics” was involved, although that probably can’t be investigated directly.

—

New info: apparently it’s 1960 for “Golden Age,” in the fanzine Comic Art, from none other than Richard A. Lupoff, future author of much SF and other work, including “With the Bentfin Boomer Boys on Little Old New Alabama,” in Again, Dangerous Visions. And picked up interestingly at Marvel, with the cover of Strange Tales 114 in 1963, with the caption including “From out of the Golden Age of Comics into the Marvel Age.”

LikeLike

Pingback: June 2023 Q&A – Adept Play